Photo by California Innocence Project Shortly before midnight on August 10, 1993, 43-year-old William Richards came home from work and discovered the body of his 40-year-old wife, Pamela. She had been severely beaten, apparently with fist-sized rocks, a cinder block, and a stepping stone, on the property where they lived in the Mojave Desert in California.

Richards became a suspect immediately because the couple had been having financial and marital difficulties. They both had sexual relationships outside the marriage and a month earlier, Richards had drawn up a document proposing a division of their property.

An autopsy showed that Pamela had been strangled and her skull had been smashed. Blood was found inside the couple’s camper as well as near a generator outside. Police confiscated Richards’ clothing, which bore only three tiny dots of blood spatter and what appeared to be blood transferred when Richards cradled his wife’s head after he found her body.

Nearly a month later, Richards was arrested and charged with first-degree murder.

He went to trial four times in San Bernardino County Superior Court before he was convicted. The first trial resulted in mistrial when the jury was unable to reach a unanimous verdict. The second trial ended in a mistrial during jury selection. The third trial resulted in a mistrial when the jury again was unable to reach a unanimous verdict.

Ten days before the fourth trial began in August 1997, the San Bernardino County District Attorney’s Office asked Dr. Norman Sperber, a dentist and forensic odontologist, to examine a photograph taken during Pamela’s autopsy that showed a crescent-shaped lesion on Pamela’s right hand.

At the trial, Dr. Sperber told the jury that based on his more than 40 years of examining bitemarks, he could say that out of 100 people, only “one or two or less” would have the same “unique feature” in their lower teeth that he found in Richards’ teeth. Dr. Sperber testified that Richards had made the bitemark on Pamela’s hand.

The prosecution also presented evidence that blue cotton fibers found in a crack of one of Pamela’s fingernails were similar in composition to fibers in the shirt Richards was wearing. The analyst who performed the comparison admitted, however, that such cotton fibers were among the most common fibers in the world.

The defense presented evidence showing that Richards clocked out of work at 11:03 p.m. on the night Pamela’s body was found. Even driving 75 miles an hour, a defense investigator testified, he did not arrive at the Richards property until 11:47 p.m.—a distance of 44.8 miles from where Richards worked. Evidence showed that Richards answered a telephone call at the property at 11:55 p.m. and told the caller that he had just found his wife’s body. Richards called 911 at 11:58 p.m. The defense argued that Richards could not have committed the crime during such a brief interval of time.

Pamela’s brother said he spoke with Pamela by telephone around 7 or 7:30 p.m. and she seemed normal, although she said she and Richards had been arguing earlier. Another witness testified that he called the residence just before 10 p.m. and no one answered.

Dr. Gregory Golden, a dentist and chief odontologist for San Bernardino County, testified that the bitemark evidence was of no value because the bitemark was generic in nature and the photograph was of low quality. Dr. Golden conceded on cross-examination, however, that the unique feature of Richards’ lower teeth could only be found in a small number of people.

Dean Gialamas, a senior criminalist with the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, examined the bloodstains on Richards’ clothes and performed numerous experiments with concrete blocks and bloodied hair. He concluded, “Given the lack of spatter on (Richards’) clothing, no, I don’t think this clothing is consistent with this individual being the perpetrator.”

On July 8, 1997, Richards was convicted of first-degree murder. He was sentenced to 25 years to life in prison.

His conviction was upheld on appeal in 2000.

In 2001, the California Innocence Project at California Western School of Law began re-investigating the case. In 2007, a state petition for a writ of habeas corpus was filed on behalf of Richards. The petition claimed that tests on the cinder block used to smash Pamela’s skull identified a male DNA that was not Richards’. DNA testing on hair from under Pamela’s fingernails also excluded Richards.

Moreover, the autopsy photograph depicting the alleged bitemark was examined and was determined to be distorted. Once the distortion was corrected, defense bitemark experts concluded that Richards was not responsible for the bitemark, according to affidavits from the experts.

And finally, Dr. Sperber recanted his trial testimony that only 1 or 2 percent of the population had Richards’ dental irregularity. “These percentages were based on my own experience and were not scientifically accurate,” he said in an affidavit for the petition. He also retracted the central conclusion of his trial testimony: “With the benefits of all of the photographs (of the crime scene and Pamela’s injuries) and with my added experience, I would not now testify as I did in 1997, and I cannot now say with certainty that the injury on the victim’s hand is a human bitemark injury.”

At the conclusion of an evidentiary hearing in 2009, San Bernardino County Superior Court Judge Brian McCarville vacated Richards’ conviction saying the evidence pointed “unerringly” to innocence.

The prosecution appealed the ruling and in 2012 the California Supreme Court, by a 4-to-3 vote, reversed the trial court’s ruling because Dr. Sperber’s recantation did not fit the state’s legal definition of “false evidence” that would allow Richards to mount a successful post-conviction challenge to his conviction.

In response, the California Legislature, in a 2014 act called the Bill Richards Bill, amended the state criminal code to state the “false evidence” should also “include opinions of experts that have either been repudiated by the expert who originally provided the opinion at a hearing or trial or that have been undermined by later scientific research or technological advances.”

A new state petition for a writ of habeas corpus was filed on behalf of Richards and in May 2016, the California Supreme Court granted the writ and vacated Richards’s conviction.

The court agreed that Sperber’s testimony was false, that the bitemark evidence was critical to the conviction, and there was a reasonable probability that without that evidence Richards would not have been convicted.

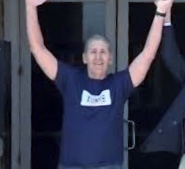

Richards was released from prison on June 21, 2016 and on June 28, 2016, the San Bernardino County District Attorney’s Office dismissed the charge.

In March 2017, Richards filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against San Bernardino County and Sperber. In September 2019, the federal lawsuit was dismissed. In June 2021, a San Bernardino County Superior Court judge declared Richards factually innocent. In July 2021, Richards was awarded $1,165,920 in compensation from the state of California. In June 2022, the Ninth Cirrcuit U.S. Court of Appeals reinstated his federal lawsuit.

– Maurice Possley

|