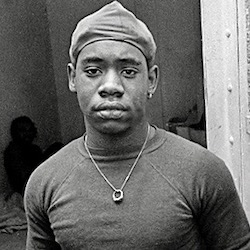

Johnny Ross (Photo by Chris Harris) After being convicted of aggravated rape and given a mandatory death sentence in Louisiana in 1975, Johnny Ross became the youngest death row inmate in the United States at age sixteen. It was not until six years later, in December of 1981, that Ross was released from prison on the basis of semen and blood analyses that showed he could not have been the rapist. On the night of July 17, 1974, a white federal law enforcement agent was driving home in St. Bernard Parish (adjacent to New Orleans) when her car was rear-ended by two black men in another vehicle. When she got out of her car to inspect the damage, the two men forced her back into her car and positioned themselves on either side of her. The two men drove the victim through the city and stopped near a warehouse, where the victim was forced at gunpoint to undress and submit to repeated acts of sexual intercourse in the back seat of her car. After the assault was over, the two men drove the woman back to the site of the abduction. By this time, St. Bernard Parish police had staked out the area after an eyewitness reported the kidnapping. When the men returned with the victim, the police moved in to capture them, at which point the perpetrators managed to drive off before they could be apprehended. A high-speed chase and gun battle ensued all the way back to New Orleans, yet the men were ultimately able to escape. After viewing photographs of potential suspects, the victim made a positive identification of a 16-year-old named Earl Lewis, a teen with a long criminal history, including 44 past arrests. When the police set out to arrest Lewis, he drew a gun at which point he was shot and killed by the officers. When police later questioned Lewis’s relatives, Johnny Ross was named as Lewis’s accomplice in the rape. Ross was arrested in his home in the early morning on July 25, 1974, and he was ostensibly advised of his rights en route to the station house. When Ross arrived at the station, he was allegedly read his rights from a Rights of Arrestee Form, which he thereafter signed. He then indicated that he wished to cooperate and speak with the officers about the matter. The officers proceeded to obtain a four-page signed confession from Ross, in the absence of any guardian or counsel. To corroborate the confession, the police sought to obtain a positive identification of Ross from the rape victim. On August 1, 1974, two weeks after the rape, the victim was shown a line-up of six young men, including Ross. Unable to identify any of the men as the assailants, the victim was then shown a photo line-up fifteen minutes later. Ross was the only person who appeared in both the live line-up and the photo line-up, and he was subsequently identified by the victim as one of the perpetrators. Ross’s testimony at the suppression hearing before his trial alleged very different facts from what police officers had reported regarding his arrest and confession. Ross admitted that he had signed a waiver of rights form, although he contended that he was not advised of his rights until after his confession had been secured. In addition, he alleged that the interrogating officers had beaten him in order to secure his signature on the confession. Ross further testified that he had asked his mother to send a doctor to the prison to treat his injuries from the police abuse. He testified that he had also shown at least one of the bruises received in the incident to a physician at central lockup. Further, he recounted that when he did finally sign the confession, only the phrase “No Statement” had been typed on each page – not the detailed four-page confession that was ultimately submitted by police. Ross's confession, however, was ultimately deemed admissible by the trial judge. At Ross’s trial in 1975, his attorney, who had met with Ross just once, failed to call Ross’s family physician or the physician from central lockup to testify to the signs of police abuse. He also failed to call people whom Ross claimed could vouch for his whereabouts on the night of the rape. In addition to Ross’s signed confession and the identification of Ross by the victim, the prosecutor introduced a thumbprint, identified as Ross’s, which was allegedly taken off a window of the victim’s car. Although there was reason to believe that the fingerprint, based on its appearance, may actually have been planted, it proved to be a final convincing piece of inculpatory evidence. The trial itself lasted approximately three hours, and it took the jury mere minutes to return a guilty verdict on the count of aggravated rape. Under Louisiana law, Ross was given the death penalty, which was the mandatory sentence for the crime of rape at that time, regardless of whether the victim had been killed. After Ross’s conviction, the Southern Poverty Law Center took an interest in his case. Convinced after only a preliminary review that he had not received a fair trial, the SPLC took on his appeal. The appeal reached the Supreme Court of Louisiana, which considered various issues regarding the pre-trial suppression hearings and the admissibility of the evidence used at trial. Regarding the confession, the Court found that Ross’s testimony concerning the events surrounding his confession was wholly uncorroborated and held that that the trial court had not erred in admitting the confession. Ross also challenged the admissibility of the victim’s testimony identifying him as one of the assailants. He contended that her identification of him was tainted by the pretrial identification procedures, which rendered its use against him a denial of his right to due process. The Court held that while the out-of-court identification may have been tainted, her in-court identification was admissible, since she had ample exposure to her assailants to identify them independent of the police identification process. Finally, Ross argued that the trial court had erred in excluding potential jurors who expressed an unwillingness to impose the death penalty, the required sentence if he were to be convicted. The Court held, however, that securing a jury willing to give the death penalty did not necessarily ensure Ross’s conviction, and he was therefore not denied a fair and impartial jury. While the Louisiana Supreme Court summarily upheld Ross’s conviction with its decision on March 7. 1977, the Court was forced to vacate Ross’s death sentence in accordance with the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Selman v. Louisiana. This decision, handed down by the Court in 1976, invalidated the mandatory death penalty provision of Louisiana’s aggravated rape statute. The result was that Ross's case was remanded to the trial court for resentencing to the most serious penalty for the next lesser included offense. Ross would therefore be resentenced to a term of twenty years imprisonment. John Carroll, Ross’s attorney and the Legal Director from the SPLC, appealed the new sentence, and in early 1980 sought to move the case into the federal court system. Carroll filed a habeas corpus petition in the U.S. District Court in New Orleans and was granted permission to conduct discovery in the case to obtain more information regarding Ross’s arrest and prosecution. Carroll then hired Gary Eldredge, a local private investigator, to help complete the investigation for the habeas petition. In the course of Eldredge’s work, he noticed in reading the trial transcript that the prosecutor had introduced into evidence the rapist’s blood type, which was determined from a sample of seminal fluid. That blood type, however, had never been explicitly tied back to Ross. For the sake of thoroughness, Eldredge contacted Ross to see if he knew his blood type. Although he did not, he informed Eldredge that he had donated blood multiple times since he’d been imprisoned. After contacting the blood bank that served the prison, Eldredge discovered that each of the numerous times Ross had donated, his blood had been typed “0 positive.” The rapist’s blood was typed "B”. Eldredge then arranged for a prominent university doctor to retest Ross'’ blood, and his tests confirmed his blood type was not that of the rapist’s. A further review of official records revealed that the blood of Earl Lewis, the young man shot and killed by the police, also did not match that of the rapist. Presented with this new evidence and the pending federal appeal, the New Orleans district attorney agreed to drop the charges against Ross. Finally cleared for the aggravated rape, Ross was released from prison on December 15, 1981 at the age of twenty-two.

– Researched by Cary Steklof

|