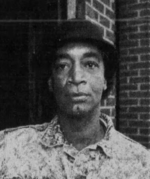

Beacon Journal Photo/Don Roese 9/21/1989 Harllel B. Jones (aka “Harllel X”) was the founder and leader of a Cleveland, Ohio organization known as “Afro Set” or the “Black Nationalist Party for Self Defense,” a militant black organization loosely aligned with the “Black Panther” movement of the late 1960s. Jones was convicted on March 28, 1972, in the Cuyahoga County Court of Common Pleas, of second-degree murder in connection with the August 7, 1970 fatal shooting of John H. Smith by members of Afro Set. Jones’ conviction was based primarily on the testimony of a co-defendant, Robert Perry, stating that Jones had ordered random shootings of police officers and security guards in retaliation for the fatal shooting of Willie Lofton, an Afro Set member, by a local security guard. According to Perry, Jones called a “red alert” meeting of Afro Set members on August 6, 1970 to order the retaliatory shootings, which were carried out by Perry and co-indictees Marvin Bobo, James Moore, and Victor Harvey. The State’s case rested on Perry’s testimony linking Afro Set members to the August 7, 1970 murder of John Smith and establishing that the members were acting at the direction of Harllel Jones. Perry, the admitted triggerman, had become a confidential informant for the FBI in the months prior to the 1972 trial and had the first-degree murder charges pending against him in connection with the Smith murder dropped in return for his testimony. In 1975, with the assistance of the ACLU, Jones filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus. On November 7, 1975, Judge Frank J. Battisti of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Ohio issued a ruling dismissing most of the grounds stated in Jones’ petition, but ruled that an evidentiary hearing was necessary as to three of his contentions regarding the denial of due process: (1) the State’s suppression of an exculpatory statement from co-indictee Victor Harvey; (2) the State’s failure to disclose a promise of leniency made to co-defendant Robert Perry, the State’s key witness; and (3) the involvement of Perry and his counsel in the strategy and planning councils of Jones’ defense. At trial, the prosecution had presented testimony by Robert Perry that, in addition to calling the “red alert” meeting and ordering random retaliatory shootings, Jones had given a shotgun to co-defendant Harvey. Perry’s testimony was corroborated by another Afro Set member, Kenneth Malone, who was not charged in connection with the shooting. Jones’ defense consisted of his denial that he ever called the “red alert” meeting, issued orders to commit random shootings, or gave a shotgun to Victor Harvey. Jones’ testimony was corroborated by James Moore and Marvin Bobo, including Bobo’s testimony that he, not Jones, had given a shotgun to Victor Harvey. Jones’ counsel had made a timely demand for, and the court had directed the prosecution to disclose, all exculpatory statements in the prosecution’s possession. Nevertheless, the prosecution failed to disclose a statement taken from Victor Harvey, then 15 years old, when he was questioned by local police officers shortly after the shooting. In this statement, Harvey made no mention of a meeting at Afro Set headquarters or of any involvement by Harllel Jones, but he mentioned that he’d seen a shotgun in the trunk of Marvin Bobo’s car - implying that it came from Bobo’s car and not from Jones. Because the State failed to produce any exculpatory statement from Harvey in response to the defense’s requests, Jones’ trial counsel assumed that Harvey had provided the police with a statement implicating Jones. As a result, not only was Jones denied access to Harvey’s statement, the State’s suppression of the statement caused Jones’ attorneys to decline to call Harvey, whose charges had been dismissed prior to the trial, as a defense witness at trial. At the evidentiary hearing on Jones’ motion for a writ of habeas corpus, the State claimed that Harvey’s statement was neutral and not favorable to Jones because the written record of the statement made no express mention of Jones, and therefore the State had no obligation to disclose it. However, Jones contended that when this statement was taken, Harvey orally stated that Jones had neither called an alert nor had prior knowledge of the killing, and produced testimony by Harvey himself and Harvey’s stepfather, who was present during the questioning, to support his argument. The district court issued its ruling on February 10, 1977, granting Jones’ petition for a writ of habeas corpus on the grounds that the State’s failure to produce the Victor Harvey statement at trial deprived Jones of his constitutional right to due process. Citing United States v. Agurs, 427 U.S. 97 (1976), the court determined that the Victor Harvey statement was sufficiently material to compel disclosure under the standard set forth in Agurs – namely, that a defendant’s constitutional rights have been violated if it can be concluded after examining the entire record that the undisclosed evidence “creates a reasonable doubt that did not otherwise exist.” The ruling also provided that Jones be released unless the State commenced new trial proceedings against him within 90 days of the order. While the State’s appeals were pending, Jones was released on $10,000 bond on June 24, 1977. The State’s appeal was heard before a 3-judge panel of the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth District on October 7, 1977. In its ruling, issued May 3, 1978, the Sixth Circuit affirmed the judgment of the district court on the same grounds as the district court. The State appealed the decision to the United States Supreme Court, and on September 29, 1978, the Supreme Court denied certiorari, ending the appeals process. After the State’s appeal failed, all parties had expected the State to commence proceedings for a new trial in Cuyahoga County, since, while the appeals were pending, Cuyahoga County Prosecutor John Corrigan had publicly stated his intention to try Jones again. However, on October 17, 1978, shortly after the Supreme Court’s denial of certiorari, Corrigan asked the Court of Common Pleas to dismiss all charges against Harllel Jones, based on the Prosecutor’s claim that key witnesses were no longer available. Harllel Jones has contended that his arrest, indictment, and conviction were the efforts of the FBI, working in conjunction with the Cuyahoga County prosecutor’s office, to silence and discredit him and neutralize him as a leader of Cleveland’s black community. – Researched by Austin Stewart

|