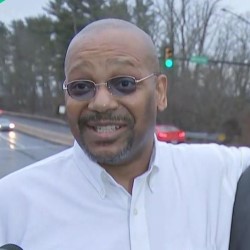

Daniel Gwynn (Photo: CBS Philadelphia)

Although abandoned and lacking electricity, the apartment building was home to several squatters, including 38-year-old Marsha Smith, who died of soot and smoke inhalation. Five other people were also injured.

Three other fires had been set at the building in the previous six months, with the most recent one occurring in September.

Officers with the Philadelphia Police Department investigated the November fire as arson and interviewed the people living in the building.

John Antrom, one of the squatters, said that there had been a fight at the building the day before the fire, when a man named “Rick” showed up and demanded sex from Smith. Antrom said that after he and Smith’s boyfriend, Donald Minnick, beat up “Rick,” the man made a vague threat against them. Antrom said that he did not know Rick’s last name but knew that he had been on probation and had a friend who worked at a carwash a few blocks away. He said Rick was about 5’9” and 170 pounds.

About three hours after the interview, according to a police report, Antrom identified 25-year-old Daniel Gwynn from a photo array as “Rick.”

Minnick’s statement to police tracked Antrom’s. In the statement, Minnick said that Rick knew a man named Glenn Taylor, who had been murdered in the building in 1993. He described Rick as 5’6” and “somewhat heavy.” Minnick was also said to have identified Gwynn from the photo array.

Terry McCullough, who was Antrom’s brother, said the fight between Rick, Antrom, and Minnick lasted about an hour. He said Rick made threats as he left the building. McCullough also told police that he thought Rick was on probation and was later said to have identified Gwynn from a photo array.

Two other persons squatting in the building, Rosalee Jones and Larry Hawkins, told police they didn’t see the fight. Jones said that Rick was the “bully of the building,” and that he had a friend at the nearby carwash. They were not shown a photo array.

Gwynn’s cousin told police that Gwynn’s reputation was “so bad around the neighborhood” that he got blamed for anything that happened. Gwynn actually lived about 1.5 miles west of the fire.

Ten days after the fire, in the early morning of November 30, Officer Joseph Surina watched Gwynn while he cruised a neighborhood a mile away from the fire. He would later testify at a suppression hearing that he didn’t recognize Gwynn as one of the people from the area, where a burglary had been reported. Surina said Gwynn had a knapsack and kept moving away each time Surina approached in his car. Surina then stopped Gwynn and asked him for identification. Gwynn said the ID was in his knapsack. Surina then frisked Gwynn and called for backup. He placed Gwynn in the cruiser, and later handcuffed him based on what he said was a belief that Gwynn was preparing to get away. A records check later showed that Gwynn had five outstanding bench warrants.

Surina arrested Gwynn and took him to the police station. The police searched Gwynn and said they found five lighters and several matchbooks on his person and additional lighters and matches in his knapsack.

Twelve hours after his arrest, Detective Dominic Mangoni read Gwynn his Miranda rights. At 3 p.m., Gwynn gave a statement, which said that he had argued with the squatters the day before the fire but could not remember what the argument was about. He said he found some gas cans and gasoline and returned to the building to apologize, but the squatters either wouldn’t talk to him or called him names. Gwynn said he was on the third floor when he dropped the gas can. He then accidentally dropped the match he was using to light his crack pipe and the gas caught fire. He said he ran down the stairs and out the door, leaving the gas container at the scene. Gwynn also said the gas he “shook out” on the third floor traveled down the steps to the second floor and that he also lit a trash fire on the first floor.

Gwynn was charged with first-degree murder, five counts of aggravated assault, and arson.

A report by the Philadelphia Fire Marshal said the fire had been set in the third-floor hallway and spread to the fourth floor, with the most extensive damage in front of two third-floor

apartments. The report said that a liquid accelerant was used. It also said there was no evidence of fire down the stairs to the second floor or on the first floor.

At a pre-trial hearing, Gwynn moved to suppress his statement. He testified that he was a crack addict and under the influence of drugs at the time of his arrest and subsequent interview. He said he was tired and confused and gave an involuntary statement based on a perceived threat from Mangoni. (Mangoni is a defendant in a lawsuit filed by Curtis Crosland, who was exonerated in 2021.)

Judge David Savitt of the Philadelphia County Court of Common Pleas denied the motion to suppress.

Also pre-trial, Gwynn’s attorney sought to challenge the identifications made by Antrom and Minnick. Their identifications had been unconventional but valid, according to the prosecutor, Paul Riley. Riley said the two men had told detectives that they had seen Gwynn’s photo nearly a year earlier when looking at the photo array for the Taylor murder, which the prosecutor called an “unrelated” homicide. Gwynn had been a filler in that array, the prosecutor said, but the array no longer existed. Judge Savitt allowed Antrom and Minnick to testify about their identifications of Gwynn. (In that photo array, Antrom and Minnick had identified a man named Gary Lupton as the person they saw beat Taylor to death. Three days before the fire, they had testified at Lupton’s trial that they knew Lupton as “Rick;” Antrom testified at that trial that Lupton threatened to have Antrom killed if he talked to the police. A jury convicted Lupton of murder on November 30, 1994, the day that police arrested Gwynn.)

There was no physical evidence directly connecting Gwynn to the fire. Lieutenant Thomas Lawson with the fire marshal’s office testified as an expert witness. He said his inspection of the building suggested that the fire may have been set in as many as four places on the third floor and involved at least three separate pours of an accelerant.

Lieutenant Arthur Czakowski, also with the fire marshal’s office, testified about his inspection of the building with Gentry, a black Labrador trained to detect accelerants. He said that the dog alerted to the presence of accelerants in four spots on the third floor. The dog also alerted to an empty canister that smelled of gasoline. No usable fingerprints were found on the canister.

Minnick testified that Gwynn showed up the day before the fire, demanding sex with Smith. Minnick said that he and Antrom beat up Gwynn, whom he referred to as “Rick.” Unlike his earlier statement to police, Minnick now said that Gwynn made no threats when he left.

Antrom’s testimony was consistent with his statement to police.

The jurors heard Gwynn’s statement to the police. Gwynn did not testify, and his attorney, Lee Mandell, did not present any witnesses. In his closing argument, he suggested that if Gwynn did start the fire, it was accidental, making Gwynn guilty only of third-degree murder.

The jury convicted Gwynn on all counts on November 2, 1995.

During the penalty phase of the trial, Gwynn testified about his drug addiction and the havoc it had wreaked. “I’m sorry for a lot of the things that I’ve done basically,” he said. “Basically everything that I’ve done in the past was good but then when I started messing with the drugs, it just took over a whole different part of my life. It was like on one side you got the devil and on the other side you got an even deeper darker devil, you know.”

The jury sentenced him to death on November 6.

Gwynn appealed his conviction, arguing that Judge Savitt erred in denying a motion to suppress the evidence seized from his knapsack and the statements Gwynn made in custody because the officer lacked probable cause to arrest him. Gwynn also said his attorney had been ineffective in presenting evidence that mitigated his culpability in the fire.

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court affirmed the conviction on November 23, 1998. It said Surina acted properly. “The suspicious nature of appellant’s behavior and the appearance of the knapsack gave the officer reasonable cause to believe that appellant might be connected to crime,” the court said. “The frisk was appropriate for the protection of the officer’s safety.”

Two judges dissented and said that Surina lacked probable cause to arrest Gwynn and place him in a cruiser while they ran his record through the system. “When Appellant was placed inside the car, he was not engaged in any act that would cause a person of reasonable caution to believe that he committed a crime,” the dissent said. “The report of a burglary and the officer’s belief that Appellant looked suspicious did not justify arresting Appellant.”

Gwynn then sought a new trial through the state’s Post-Conviction Relief Act, again asserting his trial attorney’s ineffectiveness in both the guilt and sentencing phases of his trial. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court denied his motion on March 20, 2008.

Gwynn then turned to the federal courts, filing a petition for a writ of habeas corpus in U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania on March 7, 2009. Gwynn, now represented by the Capital Habeas Unit of the Federal Community Defender Office, said that Mandell had failed to present mitigating evidence during the penalty phase of the trial.

The motion said: “At the time of his capital trial, Daniel Gwynn was a long-term cocaine addict suffering from severe mental illness and hallucinations. He had no … prior history of violence. The jury that sentenced Mr. Gwynn to death heard no evidence about the profound effects of long-term cocaine addiction on Mr. Gwynn and no evidence about his mental impairments. The jury knew almost nothing about Mr. Gwynn’s chaotic, abusive, and impoverished childhood. The reason for the jury’s ignorance is clear. The jury did not know because the lawyer who represented Mr. Gwynn did not know. The lawyer who represented Mr. Gwynn did not know because he did not look. Defense counsel’s almost complete lack of preparation for either phase of his client’s capital trial resulted in a defense that fell far short of the competent representation guaranteed by the Sixth Amendment.”

The motion also said that the state had withheld exculpatory evidence suggesting that Minnick and McCullough had previously identified Lupton as “Rick,” and that there was an obvious connection between the Taylor murder and the fire.

At the pre-trial hearing, Riley had pushed back against Mandell’s motion to suppress the witness identifications, arguing that Antrom and the others knew Gwynn. Mandell said his client didn’t know the men.

Judge Savitt said Mandell could proceed with his motion.

The prosecutor said: “He wasn’t the prime suspect in the—it’s another photo spread. He wasn’t even the prime suspect. In other words, he was a filler and the people all knew him, you already got his photo, you showed it to us on that other occasion.”

Riley said he hadn’t seen the photo spread, and it no longer existed.

“If the prosecutor was correct that the squatters told the police investigating the fire that Rick was someone in the [other] photo arrays, that fact was omitted from the police reports that were disclosed to the defense,” the motion said “Again, the fire occurred during the Taylor murder trial and at least three of the officers investigating the fire (including the officer who reportedly elicited Mr. Gwynn’s confession) also had investigated the Taylor murder.”

The federal petition was stayed while Gwynn sought habeas relief through the state courts.

Judge Benjamin Lerner of the Philadelphia County Court of Common Pleas denied Gwynn’s motion on March 27, 2012. He said the state had not committed any disclosure violations. The Lupton-Taylor case had been discussed during pre-trial hearings, and Mandell could have obtained additional information with due diligence. In addition, Judge Lerner wrote, this new evidence wasn’t particularly helpful, considering the weight of evidence against Gwynn. “The fact that the witnesses in his case had identified another individual they knew as ‘Rick’ during an unrelated criminal prosecution more than a year before petitioner committed his crime is of no import,” he wrote. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court affirmed the lower-court ruling on June 17, 2013.

Gwynn returned to his federal habeas petition. In 2010, Judge Karen Marston of U.S. District Court had granted Gwynn’s legal team broader access to the case files of the Philadelphia County District Attorney’s Office.

The search yielded several pieces of evidence suggesting that Lupton was the person the witnesses identified as “Rick.” There’s no evidence Lupton set the fire, as he was in custody while his trial was underway. But he appeared at his trial in street clothes, which according to defense filings, could have fueled the witnesses’ belief that he was at large and a threat. Furthermore, he had threatened to have his associates retaliate against the witnesses.

The new evidence said that Lupton matched the descriptions provided by the witnesses at the fire. Lupton was on probation, and he had a friend who worked at the car wash. Lupton also had a stocky build, consistent with the witness descriptions, while Gwynn was thin.

Most importantly, the search located the photo array used to identify Lupton, which the prosecutor said didn’t exist and which was said to have been used by the witnesses who were said to have remembered Gwynn’s presence as a filler. Gwynn was not one of the eight men in the array.

Gwynn incorporated this information into an amended habeas petition that was filed on October 16, 2016. He was now represented by Matthew Stiegler and Gretchen Engel of the Center for Death Penalty Litigation. Later, Attorney Karl Schwartz would join the team.

On December 18, 2020, Gwynn’s attorneys and prosecutors filed a joint stipulation to resentence Gwynn to life in prison, based on his trial attorney’s failure to adequately investigate and present mitigating evidence at the penalty phase of the trial.

The other claims in Gwynn’s habeas petition remained unresolved, as Gwynn’s attorneys and attorneys with the district attorney’s federal litigation section continued examining court records from the Smith and Taylor cases.

On February 23, 2023, the district attorney’s office agreed that Gwynn’s conviction should be vacated. The state said that although Gwynn’s claims of disclosure violations were procedurally defaulted, the state was waiving those defenses. “After thorough review, Respondents conclude that Gwynn’s rights have been violated and lack confidence in his conviction,” the response said.

“The evidence paints a compelling picture of an alternative suspect who had the means, motive, and opportunity to have an associate set the fire at issue, which tends to exculpate Gwynn,” the response said. “In addition, evidence that key witnesses identified the alternative suspect—not Gwynn—as ‘Rick,’ and the evidence that a number of identifiers the squatters used to describe ‘Rick’ fit Lupton and not Gwynn, could also have been used to impeach their testimony. This information calls into question not just the squatters’ credibility and motivations, but their entire story about being attacked and threatened the day before the fire since Lupton was in custody at the time.” In addition, the photo array, which contained no picture of Gwynn, also “further undermines the credibility of the squatters and calls the good faith of the larger investigation into question.”

In earlier habeas petitions, Gwynn’s attorneys had submitted a report by an expert witness that said his confession was not trustworthy and didn’t establish his guilt “because it contains factual errors, indications that it was not made of personal knowledge, and lacks corroboration.” The report noted the inconsistencies between Gwynn’s confessions and the facts of the case. Gwynn said he ran out the door, but the door was boarded up. He said he watched the gas spread down the hallway, but the building lacked electricity and the fire occurred before it was light.

“Respondents note that Gwynn’s confession is so thoroughly contradicted by the available physical evidence that it is unlikely that it would have been sufficient to support a guilty verdict by itself,” the state said in its response.

Judge Marston accepted the recommendation of a magistrate judge and granted Gwynn’s habeas petition on June 8, 2023. Gwynn remained in prison.

On February 28, 2024, Judge Barbara McDermott granted the state’s motion to dismiss the charges against Gwynn. He was released from prison later that day.

“I think he was probably terrified and he was intoxicated, and probably said whatever they wanted to hear,” said David Napiorski, the assistant supervisor of Federal Litigation at the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office who handled the state’s response during the habeas process. “There was wrong done here and the DA’s office is committed to correcting those wrongs when we identify them.”

– Ken Otterbourg

|