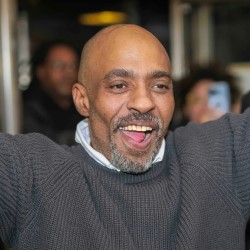

Jabar Walker (Photo: The Innocence Project)

Officers from the New York Police Department’s 30th Precinct investigated the shooting. Carlos Jimenez told officers that he saw the shooting while playing dominoes in front of 562 West 148th Street and that the shooter ran into the basement area of the building next door, at 560 West 148th Street.

The police pulled all arrest records related to that five-story apartment building. The next day, reportedly acting on a Crime Stoppers tip, they entered Apartment 2A. Jabar Walker, who was 20 years old, was there, but he left as the police arrived, leaving a small amount of drugs behind. Prior to their death, Walker’s grandparents had lived in the apartment, but it had become a place where drugs were bought and used.

Police arrested John Mobley and Robert Locust inside the apartment. Locust and Walker were cousins. Mobley lived two floors up. (Their charges were later dropped.) There is no police report memorializing any interviews with the two men about the murders. Similarly, a post-conviction investigation turned up no Crime Stoppers tip about the apartment.

At the time of the murders, the Hamilton Heights neighborhood was under siege from drug dealers and corrupt police officers. A year earlier, the scandal involving the “Dirty 30,” as the precinct was known, broke open, leading to the eventual conviction of 30 officers and dismissals of nearly 100 wrongful convictions. (Click here for more information on this group exoneration.)

The investigation into the double murder stalled for nearly two years, until May 19, 1997. At the time, Detective Elpidio De Leon was trying to close out an unrelated murder investigation from October 1994, when a man had been shot and killed in another apartment building on 148th Street.

Initially, Vanessa Vigo said she had seen that shooting and identified a potential suspect. But then the investigation went cold. When De Leon asked Vigo to again look at photos in 1997, she went to the precinct, where she was said to have again identified the shooter in that case.

De Leon then asked Vigo if she knew anything about the murders of Guzman and De La Cruz. According to his report, “Ms. Vigo said that she saw it happen and that she knew the person who did the shooting.” She said that person was “very dangerous.”

Two weeks later, De Leon and Detective Gerard Dimuro visited Vigo in her apartment. According to the police report, Vigo said that Walker was the shooter. The detectives showed Vigo two Polaroid photos of Walker, which they happened to have with them.

At the precinct the next day, Vigo gave a statement. She said she saw the shooting from her apartment window. Vigo said she had known Walker from the neighborhood for many years. She also said in the statement that Walker went by the street names “Black” and “Snoop.” Several tipsters had told the police that a man named “Black” had been the shooter.

De Leon and Dimuro interviewed Walker on June 19, 1997. He said that at the time of the murder, he was at his mother’s home in Queens and heard about what happened the next day, when a friend, Ismail Khabir, brought him back to Manhattan. The police later interviewed Walker’s mother but not Khabir. Dimuro said in his report that Walker acknowledged using the nicknames Black and Snoop.

Walker was indicted by a grand jury on two counts of second-degree murder and arrested on July 10, 1997. Vigo testified before the grand jury. She had initially told police that the shooter fired from the driver’s side of the car. But that was inconsistent with a bullet hole in the windshield. Before the grand jury and at trial, she testified that the shooter was on the passenger side. Similarly, her statement to police said she didn’t know the color of the victims’ car. At the grand jury, she said it was red.

Walker’s trial was initially set for February 9, 1998, but was pushed back two weeks. On February 19, the prosecutor, Assistant District Attorney Helen Sturm, met with Sergio Nolasco, Vigo’s brother, and entered into a proffer agreement with him. At the time, Nolasco was facing drug charges in federal court.

Separately, beginning on January 28, 1998, De Leon and Dimuro began meeting with Mobley, who at the time was in a New Jersey jail facing several years in prison. Mobley agreed to testify against Walker.

Prior to Walker’s trial in New York County Supreme Court, the state had offered him a deal to plead guilty to two counts of manslaughter, with two consecutive sentences of 10 to 20 years. On February 23, the day before the trial began, the state sweetened the deal to two consecutive sentences of nine to 18 years. Walker declined the offer.

Walker’s principal attorney was Thaniel Beinert. This was his first criminal trial. Beinert had an arrangement with two more experienced attorneys, Vincent Scala and Carl Spector, where Beinert would try to dispose of cases through pleas, and failing that, the attorneys would assist him at trial.

Just before trial, a new witness known in court records as Mr. Santiago had emerged. Santiago had looked at a photo array that included Walker but said another man in the array looked more like the shooter. The state offered to make him available to the defense, but neither Beinert nor his colleagues interviewed Santiago. Instead, the defense agreed to a stipulation drafted by the state that summarized his interview with police.

De Leon had written in a report that the murders were most likely a drug-related hit, but at trial the state took a different tack. Its theory was that a man named Felipe Garcia directed Walker to kill Guzman and De La Cruz because De La Cruz had beaten up Garcia.

Mobley testified that he had run into Walker a few weeks before the shooting and Walker had shown him a gun that he needed in order to “take care of some business.” Mobley said that Walker told him that Garcia wanted Walker to kill somebody based on a previous altercation. “They had a fight or something and Felipe wanted the guy gone.” Mobley said.

Mobley testified that he ran into Walker the day after the murders, and Walker told him he had shot the men. He also said that a few weeks after the murders, he and Walker ran into Garcia in the neighborhood, and he overheard Garcia tell Walker, “Good job.”

Vigo testified that prior to the shooting, she saw Walker and his girlfriend on 148th Street. A short while later, Guzman and De La Cruz pulled up and were eating in the car. Vigo said she saw Walker pull out a gun and shoot three times into the car from the passenger side. She said Walker then ran east, toward Amsterdam Avenue. He was wearing a hoodie, but Vigo said she could see his braids, eyebrows and forehead. Shortly after the shooting, Vigo said, she went to her mother-in-law’s apartment two blocks away and her mother-in-law called 911. Vigo said she didn’t speak to the police about what she saw for two years because “I continued to see the defendant after the shooting and I was scared.”

Walker’s attorneys knew about Vigo’s brother and asked in open court about any deals he or his sister had received. Justice Edwin Torres asked Sturm what she knew. Sturm denied the existence of any cooperation agreement based on Vigo’s assistance. The defense asked if Nolasco’s case was still open. Sturm said: “I have nothing to do with her brother. It’s my understanding he is being prosecuted federally.” (A legal filing would later note, “Sturm had more than an understanding (and her representation with the court that she didn’t know anything about it was not accurate)”).

Juan De La Cruz, Ismael’s brother, testified that he knew Garcia and that a month before the shooting he saw Ismael beat up Garcia on Amsterdam Avenue. Walker’s defense tried to ask Juan De La Cruz about whether Ismael was a drug dealer. Sturm objected, and Justice Torres sustained the objection. Juan De La Cruz said his brother earned a living from a bodega he owned. Juan De La Cruz also testified that he had no criminal convictions and his only arrest was for a case that had been dismissed.

Garcia was never charged. De Leon testified that he tried to speak with Garcia at Rikers Island, where he was being held on an unrelated charge. Garcia declined to talk, and that part of the investigation came to a halt. Mobley had testified that he met with De Leon and others about five times, but De Leon kept no records of those meetings. De Leon testified that nothing required him to prepare a report.

Carlos Jimenez had returned from the Dominican Republic to testify. He said that he had no idea it was Walker’s trial until he came to court. Jimenez testified he heard four shots, which was consistent with the firearm evidence. “I saw a person that ran by me,” he said. “They passed running. I didn’t see the face. And from one movement to the next he dropped the hoodie, the person dropped the hoodie. Jimenez, who was 6’1”, said the person was a little bit taller than him. (Walker was shorter than Jimenez.) Neither the state nor the defense asked Jimenez if Walker was the person he saw that night.

After the state’s witnesses, Walker’s defense stipulated that Mobley had a previous felony conviction and then rested without presenting any evidence. During his closing argument, Scala referred to Beinert as an “inexperienced lawyer who used to work in [their] office during law school.”

The jury convicted Walker of both counts on March 5, 1998.

At Walker’s sentencing hearing, on April 7, 1998, the state asked for the maximum allowed, 25 years to life on each count. Walker said, “I know I did not commit this crime, your Honor and that’s why I came here to trial … because I know I’m 100 percent innocent … I did not kill those people.”

Justice Torres imposed the maximum. He told Walker, “When I started law in the Homicide Bureau in the fifties, the defendant would have gone automatically to the electric chair for just one of these … so whatever sentence I mete out here is mild compared to what [could] have been installed.”

Walker appealed, arguing there had been insufficient evidence to support the conviction. The Supreme Court’s Appellate Division affirmed the conviction on January 16, 2001.

Mobley recanted his testimony in 1999, stating in a notarized letter that he falsely testified about Walker telling him he was going to kill someone and Garcia complimenting Walker on a job well done. “Those things I said weren’t true. I did that because that was wanted from me. I was in jail at the time and wasn’t really giving [sic] a chance not to be there. I’m writing this because it isn’t right for a man [sic] life to be taking [sic] away for someone not telling the truth. I called Mr. [Walker’s] lawyers the day of sentence but it was too late.”

Walker filed a motion for a new trial based on actual innocence in 2019, which later included a more detailed account of Mobley’s recantation. In his affidavit, Mobley said detectives from the 30th Precinct told him that he knew about the shooting and implied that if Mobley didn’t cooperate “there were other homicides that [he] could be charged with.” Mobley said he “felt I had no choice” and “told them what they wanted to hear.”

While Walker’s motion was pending, Jay Holder, the director of the National Executive Council at Columbia University’s Center for Justice contacted the Innocence Project and asked the organization to represent Walker. Holder had met Walker while both men were incarcerated at Sing Sing Correctional Facility. He believed that Walker was wrongfully convicted and that his refusal to take a plea deal for a crime he did not commit had cost him decades of freedom.

The Innocence Project contacted the Post-Conviction Justice Unit of the New York County District Attorney’s Office, and the two sides worked collaboratively to reinvestigate the case. In a letter to District Attorney Alvin Bragg outlining the findings of the review, Vanessa Potkin, the director of special litigation at the Innocence Project, said the effort “exemplified the best of conviction integrity review.”

The review found numerous flaws in the conviction.

First, the state failed to disclose exculpatory evidence. It didn’t tell Walker’s defense that Vigo had received housing benefits and that Jimenez had told investigators that Walker was not the person he saw shoot the two victims. More importantly, the defense wasn’t told that in the murder case that first put Vigo in contact with the detectives, her identification of the suspect turned out to be false because the man was out-of-state at the time of the crime.

The investigation also uncovered problems with Vigo’s testimony. She testified that her mother-in-law called 911. Vigo’s husband at the time told the post-conviction review team that was false. His mother was in Jacksonville, Florida, at the time, caring for her own mother. Vigo also testified falsely that she did not receive any benefits in exchange for her testimony. (Sturm told jurors in closing arguments that Vigo had received “no consideration in connection with her testimony.”)

In her interviews with the post-conviction review team, Vigo gave a new account of what she said she saw. Now, she said that Walker wore a mask made of pantyhose, but she knew it was him because of his thick braids. This fact wasn’t in any police report.

The post-conviction review team interviewed Juan De La Cruz in July 2023. He said his testimony had been misleading. While his brother did derive some income from the bodega, he also sold drugs, and the friction between Ismael and Felipe Garcia was based on the two men selling drugs near each other along Amsterdam Avenue. Separately, Juan De La Cruz had testified falsely about his police record. At the time of the trial, he had an open arrest warrant.

The review also found evidence that that the police fabricated evidence to connect Walker to the murders, including Walker’s statement that he used the nickname “Black.” His family and acquaintances were unequivocal that he went by either “Jab” or “Bar.” Vigo had told the post-conviction review team that Walker called himself “Black” because he was depressed. In her letter, Potkin said that explanation was “frankly absurd.”

There was also evidence that the police falsified a report from May 5, 1996. The typed report said that a Crime Stoppers caller said the shooter was named Tony Moore. At some point, the word “Jamal” was typed over “Tony.” Walker had been arrested on May 4, 1994, and used the alias Tony Moore. He was also arrested on June 24, 1996, six weeks after the report’s creation, and given the police another alias, Jamal Moore. “This leads to the conclusion that,” Potkin wrote, “once Jabar became the target of the double-homicide investigation, Dimuro added and/or altered the latter paragraph to this [report].”

In addition, the review found new evidence suggesting Walker’s innocence and corroborating his account of his whereabouts at the time of the shooting. Throughout 1996, the police received several tips about the shooting, linking the murders to a man named “Black,” and suggesting that the man was still around. “Everyone is afraid to come forward because subject has not left neighborhood,” said one tip.

But Walker was living in Atlanta in 1996, cleaning airplanes and staying with his aunt and her family. Court documents established his presence there, at odds with the Crime Stoppers tips that the shooter “has not left.”

In addition, Khabir told the post-conviction review team that he brought Walker back to Manhattan on May 29, 1995, and when they arrived in the neighborhood people were talking about the double murder.

On November 27, 2023, the district attorney’s office consented to Walker’s motion for a new trial and asked a judge to dismiss his case. The state filing said that Mobley’s recantation was credible, “leaves no evidence of motive and renders the case a one eyewitness case with no supporting forensic evidence linking [Walker] to the crime.”

In addition, Jimenez’s statements undermined Vigo’s testimony. He knew Walker and didn’t see him on 148th Street on the night of the shooting. “The defense did not adequately probe Mr. Jimenez’s failure to identify Mr. Moore at trial,” the motion said, adding that Walker’s defense team did an ineffective job in cross-examining Mobley and Vigo.

The filing said the state no longer had confidence in Vigo’s account of the crime, which had shifted over the years. It noted that she had provided an unreliable identification in another murder investigation. The state’s filing did not include any mention of police or prosecutorial misconduct.

That same day, Justice Miriam Best of New York County Supreme Court threw out Walker’s convictions and dismissed his charges.

“It has been a long road, and you made it,” Potkin said to Walker and the court.

Walker’s mother, Patrice Walker, told the New York Post: “I’m feeling so good. My stomach is jumping like crazy. I can’t stop it, but to hold him out in the hall, then I will really know he’s home to stay,” she said shortly before her son left the courtroom a free man.

– Ken Otterbourg

|