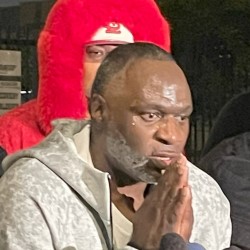

Patrick Taylor (Photo: The Exoneration Project)

Lovings and three friends—Michael Barraza, Marya Klein, and Armando Vera—had been at the apartment, and the friends told police that two Black men with guns entered the residence and told everyone to lie on the floor and not look at them. One of the men wore an orange jumpsuit, and he threatened to kill Lovings and his friends if they didn’t cooperate.

While the robbery was in progress, two other friends—Kevin Gholston and Veljko Bjelica—showed up at the apartment. They knocked on the door, and the man in the orange jumpsuit let them in. The assailants forced Lovings to open a safe in the bedroom. They then asked about a second safe. Lovings said it wasn’t his, and he didn’t have the combination. Lovings told the men that they had all the money and marijuana they had come for. The witnesses, many who had cushion cases over their heads, heard a struggle and then two shots. One killed Lovings. The other wounded Barraza. The assailants ran out of the house. Multiple witnesses linked the assailants to a beige SUV.

Dan Cook of the Rolling Meadows Police Department led the investigation and interviewed the witnesses. Bjelica told Cook that the first intruder was 25 to 30 years old, 5’10” tall, 190 pounds, with “razor-short hair” and a “very dark” complexion. He said this man wore a two-piece orange jumpsuit. Bjelica described the second man as 25 to 30 years old, 5’10” tall, 200 pounds, with a light complexion, wearing a light blue shirt and blue jeans.

Within a week of the murder, police created a composite sketch with Barazza of the man in the orange jumpsuit. Separately, the police asked Vera and Barraza to look at photo arrays containing pictures of two men said to be involved in a home invasion in a nearby town. Neither Vera nor Barraza made an identification.

The investigation appeared to run cold, and the police told a reporter for a local newspaper in mid-September 2006 that there appeared to be a lack of cooperation from Lovings’s friends and family. At the time of his death, Lovings worked as a music producer and in his father’s fast-food business. He also sold marijuana.

On October 3, 2006, Cook learned that Bjelica had told another officer that one of the assailants might be a man known as “Black Pat,” who lived in Harvey, a south suburb of Chicago. Black Pat was the nickname of 38-year-old Patrick Taylor.

On October 4, 2006, Bjelica identified Taylor from a photo array, selecting him as the intruder in the orange jumpsuit. Barraza looked at a similar array the next day but made no identification. Gholston, Klein, and Vera each viewed arrays containing Taylor’s photo and selected him as one of the intruders. Gholston’s identification was tentative and he requested to see Taylor in a live lineup.

Cook located Taylor in January 2007. At the time, Taylor was recovering from extensive injuries he received in an unrelated shooting. Cook would later testify that he didn’t arrest Taylor because he wasn’t a flight risk and because the government wouldn’t have been able to properly care for him.

Bjelica had told police he heard about Taylor from one of Lovings’s brothers, who in turn said he learned of this information from a man named Kenneth Slaughter. Police interviewed Slaughter in August 2007. He said that a short while after the murder, he saw Taylor driving around in a new car and bragging about his money. He said that when he asked Taylor how he had come into this new wealth, Taylor said, “I had to lay a mother f----- down.” Slaughter said he asked who, and Taylor responded, a “shorty at Popeyes,” referring to the fast-food restaurant. Slaughter said he was sure that Taylor meant Lovings.

Police finally arrested Taylor on August 6, 2007 and charged him with murder. He was still healing from his injuries, requiring a walker and a colostomy bag. He requested the use of a wheelchair, which presented challenges for conducting a lineup. Cook and the other officers conducted a sequential lineup, where witnesses viewed the suspect and fillers one after another.

When initially brought in for viewing, Taylor was in medical distress and caused a commotion before law-enforcement called for paramedics. Taylor was the only person in the lineup on a gurney, while the fillers sat in chairs having their blood pressure taken. Klein and Bjelica selected Taylor before the paramedics arrived. Gholston, who also selected Taylor, would later note that Taylor was fighting with the healthcare workers and trying to cover his face. Vera also selected Taylor.

Prior to trial in Cook County Circuit Court, Taylor moved to suppress the witness identifications. His attorney argued that his photograph in the array was too different from the fillers. Taylor also said the lineup identifications were too suggestive to be admissible.

The witnesses and police officers testified about the viewings. Cook testified that Taylor began screaming after he was brought in for a viewing and had to be restrained by paramedics. He said none of the witnesses selected any of the fillers.

Gholston testified that when he went to the Rolling Meadows police station to view a lineup, the paramedics brought Taylor in a wheelchair. He said that Taylor was fighting them and trying to block his face with his hands. Prior to that viewing, Gholston said, he had already made up his mind about Taylor’s involvement in the murder, based on the photo array.

Klein testified that when she went into the viewing room, she saw only one person through the glass, and he was one of the robbers whom she had seen in a previous photo array. She said that the man was sitting in an office chair and “moving around and just yelling.”

An investigator with the Cook County public defender’s office testified that Gholston told her that he had only viewed one person, Taylor, during the lineup and that it appeared he had been shot and was using a colostomy bag.

Judge Hyman Riebman denied the motion to suppress.

Separately, the state had filed a motion to bar the testimony of Dr. Daniel Wright, a professor of legal psychology at Florida International University who studied event memory. At the hearing, Wright testified for the defense about the public misconceptions involving memory. He said that memory wasn’t about retrieving a “snapshot” from a file cabinet. Memory was dynamic, Wright said, and it changed as people received new information about past events. He testified that highly stressful or emotional situations could alter a person’s memory and that witnesses sometimes change their recollections to align with each other more closely, a process known as “memory conformity.”

During cross-examination, Wright said that he could not say with absolute certainty whether any of the factors he described would have affected the eyewitnesses in this case. Rather, he said that he was “looking at what happens for humans in general.”

Judge Riebman granted the state’s motion, ruling that the jury didn’t need an expert to understand the issues Wright raised.

In 2009, while Taylor awaited trial, the police arrested a man named Arthur Patterson on the west side of Chicago and recovered a .40 caliber Glock handgun. The police tested the weapon and determined it was the same gun used to shoot Lovings, as well as a Chicago police officer named Larry Neumann in April 2006.

In that investigation, Neumann identified a man named Marcus Gordon as the person who shot him, but no arrest was made. Cook interviewed Patterson, who said he got the weapon from a man named Aaron Feazell. Patterson told Cook he did not know Taylor and after viewing his photograph said he had never seen him. Cook spoke to a second person, Ray Gary Jr., who confirmed Patterson’s account.

Gordon bore a strong resemblance to the composite sketch. The state had moved to bar the sketch and evidence about Gordon from trial. It argued that guns are easily passed around and that the similarities between Gordon and the composite sketch was meaningless. It said in a filing: “They could have fit any number of people throughout the area. And the key factor that still remains is that all these cases are unsolved cases. The only [case] involving Marcus Gordon didn’t get charged because the identifications were not good enough.”

The trial judge denied the state’s motion.

During opening statements, a prosecutor told jurors that Lovings was a generous friend with a successful career selling marijuana. Taylor wanted a piece of that success, he said.

Taylor’s attorneys noted there was no physical or forensic evidence connecting Taylor with the crime.

Vera, Klein, Bjelica, and Gholston testified about the home invasion. Each identified Taylor as the assailant who wore the orange jumpsuit. Klein testified that she was sure Taylor was the assailant, but she also acknowledged that he didn’t look like the man in the composite sketch.

Slaughter testified about running into Taylor in the weeks after the shooting and Taylor’s response to his query about the source of his newfound money.

A firearm expert with the Illinois State Police testified that based on shell casings, the weapon recovered from Patterson was the same weapon used to shoot Lovings and Neumann. Neumann testified about his shooting, identifying Gordon as the person he believed shot him.

During Cook’s testimony, Assistant State’s Attorney Michael Clarke asked him: “During the course of your investigation, did you investigate—did you get information pertaining to a Marcus Gordon.”

Cook said he did.

“Was he ever considered a suspect in the homicide of Marquis Lovings?”

“Absolutely not.”

During closing arguments, the state asked jurors to trust the identifications of the eyewitnesses who said they saw Taylor commit the robbery and murder. “You know what that face looks like,” a prosecutor said. “It’s his face.”

But public defender James Mullenix said Taylor had been railroaded by Lovings’s family, in part to draw attention away from Lovings’s drug business. Mullenix noted that 15 pounds of marijuana were found in a duffel bag at the Rolling Meadows apartment. “How do we get from the sketch to Patrick Taylor?” Mullenix asked. “We get there through Lovings’s family members who spoon-fed information to [Bjelica], who spoon-fed information to police.”

The jury convicted Taylor of first-degree murder on July 6, 2011. On November 3, 2011, he received a sentence of life in prison. Judge Riebman cited his three previous felony convictions and called him a “lifetime sociopath” who was “lacking in human decency.”

Taylor spoke at the sentencing hearing and proclaimed his innocence. He said: “They had no physical evidence on me that I committed this crime. No fingerprints match me. No phone records put me in the house.”

He said that his conviction would be overturned and then he would collect millions in a lawsuit. “I’ll buy me a big house in Rolling Meadows ’cause you paid for it,” he said.

Taylor appealed his conviction, arguing that Judge Riebman improperly excluded the expert testimony on memory. The First District of the Appellate Court of Illinois affirmed the conviction on October 30, 2014. The court said that trial judges had broad discretion in admitting expert testimony and that Judge Riebman’s decision to hold an evidentiary hearing indicated he conducted a thorough review.

As Taylor’s attorney prepared an appeal, the Illinois Supreme Court ruled in a separate case, upholding a lower-court ruling that overturned the conviction of Eduardo Lerma, who had also been barred from presenting expert testimony about problems with witness identification. (He was later convicted at retrial.) In that decision, the court wrote that there “had been a dramatic shift in the legal landscape, as expert testimony concerning the reliability of eyewitness testimony has moved from novel and uncertain to settled and widely accepted.” The research into memory, the court said, was often counterintuitive and unfamiliar to the average person, making it “perfectly proper subject” for expert testimony.

The Illinois Supreme Court instructed the appellate court to reevaluate its ruling in Taylor’s case based on the Lerma decision.

The appellate court reversed itself on September 22, 2016 and granted Taylor a new trial. It said that in light of the Supreme Court’s ruling in the Lerma case, Judge Riebman erred in excluding Wright’s testimony, "which would have been relevant in a case where the accuracy of eyewitness identifications was critical, would have aided the jurors by providing them information beyond their common knowledge, and would not have been unduly prejudicial.”

Taylor was released from prison but remained in jail, with his bond set at $3.5 million.

Taylor’s new defense team—led by Elliot Slosar of the Exoneration Project and Steven Greenberg—prepared for a retrial, filing discovery requests for police files on the case.

In 2017, Slaughter recanted his statement to police and trial testimony and said that he was coerced by Cook to falsely implicate Taylor in the murder. Another witness, Jeffrey Nowden, also recanted. Nowden didn’t testify but had given police a statement that Taylor told him about the home invasion. In 2018, he told the police and later investigators for Taylor’s defense that he didn’t hear this information directly from Taylor but rather from a man named EJ.

On September 29, 2020, Clarke, the assistant prosecutor, wrote an email to Slosar and Greenberg regarding their discovery requests. He wrote: “I have conducted a search for any of these materials that may be in the possession of the Rolling Meadows Police Department and the Streamwood Police Department.” He attached a handful of files.

On March 14, 2023, Taylor filed a new discovery request. In particular, Taylor was looking for video and still pictures that might show a light-colored SUV driving away from the crime scene or being present at Loving’s funeral. Given the years’ worth of discovery issues, Taylor’s team also requested to inspect the original investigative file maintained by the Rolling Meadows Police Department.

Judge Ellen Beth Mandeltort granted the request on April 5, 2023. Two days later, the state offered Taylor a deal to plead guilty to aggravated battery and be released on time served. The State’s offer was conditioned on acceptance prior to the inspection of the Rolling Meadows police files. At that point, the offer would expire.

At a hearing on the morning April 12, 2023, Slosar said Taylor was seriously considering the plea offer, but he and Greenberg still needed to inspect the complete investigative file. “It would be an unknowing plea for me not to look at that file to see if there’s additional exculpatory evidence in there.” Judge Mandeltort recessed the hearing until 2 p.m. to allow an initial review of the file.

At the afternoon session, Slosar described the homicide file as four large tubs “containing material that primarily had never been disclosed.” This included evidence pointing toward Feazell as an alternate suspect, based on his ownership of a beige SUV. The file also contained documents that links Feazell to Gordon, the primary alternate suspect from Taylor’s first trial. Slosar asked for the evening to review the hundreds of pages that they were able to copy, and Judge Mandeltort set a hearing for the next morning.

By the time of the hearing the following morning, Taylor’s team reviewed a small portion of the withheld material and filed a Motion to Dismiss that noted the state’s failure to turn over exculpatory evidence in a timely fashion. “It is unfathomable that days before trial these materials have now been suddenly discovered,” the motion said. “The more logical explanation is that they have been hidden from the defense.”

The motion noted that there was no file on Marcus Gordon, the man who looked like the composite sketch and was linked to the gun used to kill Lovings. Either the file had been lost, or Cook had testified falsely when he said he investigated and got information on Gordon.

At the court hearing that day, Clarke backed off the State’s prior stance that the offer would expire and appeared to acknowledge the extent of the problem. “It was clear and apparent from the review of the file that there was material in there that was not tendered to the State,” he said. “It was not in our possession.” This appeared to contradict his email from nearly three years earlier, which said he had conducted a search for this material.

Four days later, Taylor’s attorneys moved for additional discovery beyond the materials released by the police department.

In its response to the motion to dismiss and for additional discovery, the State said that much of the material contained in the boxes was either not exculpatory or duplicative of other records. In addition, the state said there had been no deception by Clarke in his response to discovery requests by Taylor’s attorneys. “What the defense fails to advise the court is that this diligent search consisted of verbally speaking with members of the Rolling Meadows and Streamwood police departments to obtain additional reports for the defense.”

The response to the motion also said Cook had not testified falsely about Gordon. He was asked a two-part question, whether he had investigated or had information about Gordon. The motion said he only answered the second part. There was no investigation, which meant there was no need for a file.

On September 28, 2023, Taylor filed a supplement to his motion to dismiss, based on a more complete review of more than 10,000 pages of records received in April 2023.

The supplemental motion said the State failed to disclose evidence suggesting that Lovings’s brothers were extensively involved in the drug business and were antagonistic toward the gang Taylor was affiliated with, providing motives for them to steer the investigation to a false conclusion.

The supplement also alleged that the state failed to disclose additional exculpatory evidence documenting the extent of Cook’s investigation into Feazell and tying a beige SUV to the shooting.

At trial, Slaughter had testified about Taylor’s swagger and new car. The new records indicated that after Slaughter made this statement to police, Cook ran a motor-vehicle check on Taylor. The records didn’t turn up any new registrations. Because this evidence wasn’t disclosed, the motion said, Taylor’s attorney was unable to impeach Slaughter’s testimony.

Within a week of filing his supplement, Taylor also filed a brief in support of his motion to dismiss. There, Taylor sought discovery that would have shed light on whether the prosecutor’s office knew that the police department was withholding exculpatory evidence. The new brief also requested an evidentiary hearing so that Taylor could have an opportunity to question Cook and anyone else implicated in the scandal.

Less than a week after this filing, the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office moved to dismiss the case. On October 11, 2023, Judge Mandeltort granted the state’s motion to dismiss the case.

The Cook County State’s Attorney Office said in a statement: “Upon reviewing these previously unaccounted-for documents and considering the deterioration of evidence, we determined that we would be unable to meet our burden of proof if the case was retried.”

Taylor was released from jail that day.

After the hearing, Slosar told the Naperville Sun, “Even prior to Pat’s 2011 trial, the state had really conclusive evidence as to who really did this murder and continued to plow forward with Pat’s wrongful trial and wrongful conviction.”

– Ken Otterbourg

|