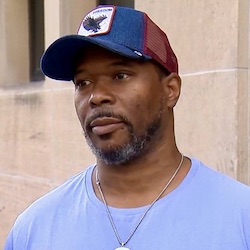

Adam Carmon (Photo: WTNH/News 8)

Troutman told police that just prior to the shooting, she was looking out the window as she waited for a taxi. She said she saw a Black male walk by wearing a ski mask and a hoodie. The man returned, she said, and began firing.

Police found 15 shell casings outside the building and five spent bullets inside the apartment.

The shooting garnered much attention. Then-Governor Lowell Weicker called attention to the baby’s death in his state of the state address several weeks later, citing the need for passage of a package of anti-gun violence reforms, including measures to stop gun thefts.

Arthur Brantley, a drug dealer, was an initial suspect because he had gotten into a fist fight when he attempted to collect a drug debt at the apartment at 2 p.m.—eight hours before the shooting. Brantley denied any involvement and agreed to take a polygraph examination. After he was told his answers indicated deception and was given his Miranda warnings, he gave the first of two sworn, recorded statements on February 5. In this statement, Brantley said he tried to contact Anthony Little, the man for whom Brantley sold drugs, to obtain a gun or “backup” so that he could seek revenge against Richard Troutman.

Brantley gave his second statement on February 7, claiming he wanted to correct his first statement. In his second statement, Brantley said he left his home at 9:50 p.m. and got into Little’s car with Demetrius Bates, who had a nine-millimeter pistol. Little said he was going to drop Bates off at a church near 810 Orchard Street and would return “when I hear gunshots.” Brantley said he suggested they just rob the place, but Bates said he was going to just “shoot it up right quick and jump back in the car.” Brantley said Bates left the car and then he heard nine to 11 gunshots. Bates got back in the car, and they fled. Little, who was wanted for escape from parole and larceny, could not be located initially.

On February 7, a shooting was reported on Townsend Street that left Anthony Stevenson wounded. Police recovered a nine-millimeter Browning semi-automatic pistol at the scene. The gun was sent to James Stephenson, a New Haven police detective, who examined the gun and test-fired it. He would later testify that he concluded that the gun was the weapon which had been used in the Orchard Street shooting. Stephenson was unable to compare the spent bullets found in the Orchard Street apartment with the gun because some damage had been done to the gun’s barrel.

On February 10, police interviewed Anthony Stevenson at the hospital where he was being treated for his wounds. Stevenson said that he had been given the gun by 21-year-old Adam Carmon, and they planned to rip off some drug dealers. Stevenson said that Carmon arranged to purchase drugs and got into the back seat of a car with the prospective sellers. Stevenson approached the driver, pointed the gun and took two ounces of cocaine from the man. Before he could get away, the man in the passenger seat shot Stevenson twice. The car sped off, leaving Stevenson on the street with the gun and the cocaine lying next to him. Stevenson claimed that Carmon had scraped the inside of the gun’s barrel with a screwdriver before he handed the gun to Stevenson for the drug deal rip-off.

On February 12, police interviewed Timothy McDonald, who said that he had gotten the gun from two juveniles, who had stolen it from the home of a friend’s father. McDonald said he had sold the gun for $200 to Carmon.

Police located two witnesses to the shooting that killed Taft, Jaime Stanley and Raymond Jones, who were in a car driving past the Orchard Street building when the shooting occurred. On February 16, Jones identified Carmon in a photographic lineup. Stanley, who was a passenger in the car driven by Jones, said that she was four to six feet from the gunman when the shots were fired. Ultimately, on February 22, she identified Carmon as the gunman in a procedure that would later be described as highly biased and suggestive.

On February 23, 1994. Carmon was arrested. He was charged with first-degree murder, first-degree assault, and illegal possession of a firearm.

In March 1995, Carmon went to trial in New Haven County Superior Court. The prosecutor, New Haven State’s Attorney Michael Dearington, argued that drugs were being sold out of Troutman’s apartment and that the shooting was done in retaliation for a money dispute in the drug trade.

Detective Stephenson testified that he examined spent cartridges ejected after he test-fired the gun recovered from Stevenson. He said that the test-fired cartridges had “very significant” breech face markings. He said that he compared the casings found outside the Orchard Street apartment to the test-fired casings. He testified there was “no doubt” in his mind that the casings found at Orchard Street had been fired by the gun.

Anthony Stevenson testified about how Carmon and he planned the drug dealer rip-off and how it resulted in Stevenson getting shot.

Stanley testified that she and Jones were in a car stopped at a traffic light at the corner of Orchard and Munson Streets. She said she saw a Black man stop in front of 810 Orchard Street and then go inside the entrance. She said that as Jones drove onto Orchard Street, the man came back outside, looked at the window, and began firing. She said she was four to six feet away and saw the shooter for about three seconds. She testified that she told police the face looked familiar.

Stanley testified that she was shown photographic lineups on six different occasions, but she did not make identification. She told the jury that she told police she didn’t feel comfortable making an identification from photographs and wanted to see a live lineup. She said the photos were too confusing, and it was too important a matter to make an identification from photographs.

She said that on February 22, 1994, police brought Stanley to a courtroom where Carmon, as well as about a dozen other men, were being arraigned on unrelated charges. When the men were brought into the courtroom, handcuffed and some in leg chains, Stanley said she recognized Carmon as the Orchard Street gunman. Stanley re-affirmed her identification at the trial and said there was no doubt in her mind that Carmon was the gunman.

New Haven Detective Ralph DiNello testified that he showed Stanley numerous photographs that included a photograph of Carmon. DiNello said Stanley did not identify Carmon, though she did say that his photo “looks very close, very similar.” DiNello said that Stanley said she preferred to see the individual in person rather than a photograph.

Detective Anthony DiLullo testified that he showed photos to Stanley on two occasions, with each session containing 50 photographs. DiLullo testified that Stanley did select a photograph of Carmon as a look-alike to the gunman. DiLullo also said that when he took Stanley to the courtroom on February 22, Carmon, upon entering the courtroom, said, “Oh, shit,” bowed his head and covered his face with his hands.

Brantley was called as a witness and recanted all of his prior statements. He said everything he had told the police before was false. He said that on February 18, police had contacted him to let him know they “made a mistake.” Brantley said the detectives said they wanted him “to correct the statements [he] gave before,” because they had “found the gun” and identified Carmon as the person “who killed the kid.” Brantley had then given a third statement in which he recanted his prior statements and denied any knowledge or involvement in the shooting.

The defense introduced portions of Brantley’s first two statements for their truth. Over defense objection, the prosecution then introduced Brantley’s third statement in which he recanted the first two statements.

After the prosecution finished presenting its evidence, Dearington produced an evidence envelope containing 18 photographs of Black male suspects, including two of Carmon, that had been shown to witnesses during the investigation. Dearington had previously reported that police had not preserved any of the photographs shown to Stanley and, in belatedly turning over the 18 photographs, denied that any had been shown to Stanley. A detective’s notation on the back of one of the 18 photographs, however, indicated that Stanley had picked another suspect, David Myles, not Carmon, as a “look-alike” to the shooter.

Prosecutor Dearington also did not disclose mugshot photographs of the other men seated next to Carmon at the February 22 “arraignment array.” At the time of Stanley’s identification, Carmon was 5 feet 6 inches tall, weighed 150 pounds, and had no facial hair. While eight of the men were also Black, three were white. Four of the other men were aged 30 or over, and two were more than 40 years old. Four were six feet tall or taller. Three weighed 200 pounds or more. Seven appeared to have facial hair. Only one was similar to Carmon in race, age, height and weight and a lack of facial hair.

Jones, the driver of the car in which Stanley was riding, had not been located when the trial started. However, on the night of Friday, March 31, 1995, after the presentation of all of the evidence in the case had ended, police arrested Jones on a material witness warrant. At the time, Jones was carrying a .40-caliber pistol and drugs. On Monday, April 3, 1995, the trial judge allowed the prosecution to call Jones as a witness.

Jones denied that he was facing any criminal charges when he identified Carmon as the gunman. Dearington, the prosecutor, had provided a hand-written list of Jones’s prior record, which was unusual, the judge noted, because usually such lists are in the form of a computer printout. Dearington told the defense and the judge that Jones did not have any pending charges at the time of the identification.

On April 7, 1995, the jury convicted Carmon of first-degree murder, assault, and illegal possession of a firearm. He was sentenced to 85 years in prison.

The Appellate Court of Connecticut affirmed the conviction in March 1998. The Court concluded that Brantley’s third statement should have been excluded as hearsay because it was consistent with Brantley’s trial testimony; however, the Court concluded the error was harmless in light of the eyewitness and firearms testimony.

Over the next two decades, Carmon filed five different state court petitions for a writ of habeas corpus challenging his conviction. All of them failed. In 2019, Carmon filed a federal petition for a writ of habeas corpus alleging that the prosecution had concealed exculpatory evidence. That case was put on hold so that Carmon could return to state court where, in July 2019, Carmon filed a sixth state court petition for a writ of habeas corpus.

Ultimately, in April 2022, attorney David Keenan, joined by attorney Doug Lieb and attorneys from Skadden Arps Slate Meagher & Flom and Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholler, filed a 138-page amended petition that cited about 50 different items, including police reports and prosecutor notes, that had not been disclosed to the defense prior to Carmon’s trial. The documents contained evidence pointing to Little and Brantley as the real perpetrators of the crime and also contained evidence that impeached both eyewitnesses—Stanley and Jones—as well as the detectives, the firearms analyst, and the prosecutor, Dearington.

On November 30, 2022, following an evidentiary hearing, Senior Judge Jon Alander issued a 51-page ruling granting Carmon a new trial. The judge excoriated Dearington for the “mountain” of exculpatory evidence that was not disclosed as well as for falsely reporting that Jones had no pending charges and for allowing Jones to falsely testify that he did not have any pending charges.

The judge specifically ruled that the following items were among those which had been improperly withheld:

—A police report that impeached Brantley’s testimony that he never contacted the police and did not voluntarily go to police to report additional information. The report, the judge ruled, “supports a claim that Brantley’s statement inculpating Little in the shooting was true” and potentially would have supported a defense claim that Little was behind the Orchard

Street shooting.

—Three additional police reports corroborating the involvement of Little as well as calling “into question the integrity of the police investigation,” the judge noted. Little was allowed to walk out of the police station even though he had outstanding arrest warrants. “The fact that Little was not arrested…could have been used to show that police were now focused on [Carmon] as the shooter to the exclusion of all others,” the judge declared.

—The late disclosure by the prosecution of the photographs that had been shown to witnesses, including Stanley. Among them was a photograph of another man—not Carmon—which bore the notation: “Pick as a look a like to the shooter at 810 Orchard.” The judge noted that disclosure came a week after the prosecution’s “express statement…that the photo arrays had not been preserved.” The judge noted that the photo of David Myles impeached the testimony of Detectives DiLullo and DiNello that Stanley had chosen Carmon as a look-alike. The judge also said it impeached Stanley’s testimony. The judge said that “the suppressed evidence established that Stanley was shown one or more photos of [Carmon] and failed to identify his photo at all….The state’s misrepresentation [that the photos were not available] together with the extreme lateness of the disclosure resulted in the defense’s failure to discover the notation and to make effective use of it at trial.”

—A report by Detective DiLullo which reported that Stanley said that after viewing all of the photographs, she “could not” make an identification. The report could have been used to impeach Stanley’s testimony that she chose not to make an identification because she wanted to see people in a live lineup instead of in a photograph array. “The fact that she could not make a positive identification…after being shown his photo is undoubtedly important,” the judge said.

—Prosecutor Dearington’s notes of an interview with Stanley in which she said she had “poor close vision.” These notes could have been used to impeach Stanley since she said she was four to six feet from the gunman.

—The photographs from the arraignment court when Stanley said she recognized Carmon as the gunman. The judge noted, “The arraignment array involving [Carmon] was exceedingly suggestive. The judge noted that a defense expert testified at the hearing that Stanley identified Carmon in a “highly biased” procedure.

—Records showing that Jones did have charges pending when he falsely testified that he did not. “More problematic is the false representation by the state to the court and defense counsel that no charges were pending against Jones at the time he gave his statement to police and made his identification of the petitioner,” the judge noted. “The prosecutor’s representation was false.”

—The bench notes of firearms analyst Stephenson were not disclosed and could have been used to impeach his testimony that the gun was used in the Orchard Street shooting, the judge ruled. “The suppressed bench notes from the 810 Orchard Street shooting contain no drawings or illustrations of the primer breech face marks on the cartridge casings on which Stephenson based his identification of the nine millimeter handgun as the source of the fired casings. The bench notes also fail to contain any meaningful description of the breech face marks,” the judge ruled.

—Stephenson’s four queries of the General Rifling Characteristics database to determine the type of handgun which could have fired the bullets recovered inside the Orchard Street apartment were not disclosed. After three inquiries failed to generate a weapon, Stephenson asked the database for measurements for all Browning firearms, generating measurements for 66 Browning firearms. Stephenson admitted at the evidentiary hearing that he showed the weapon that came closest to the measurements of the bullets recovered from the apartment. “The failure of the first three queries by Stephenson to yield a Browning firearm and the inexact result of the fourth query of all Browning manufactured firearms contained in the database would be useful during cross examination in challenging Stephenson's conclusion that the Browning firearm connected to the petitioner was the murder weapon,” the judge said.

The judge also noted that Stephenson had testified at the hearing that at trial he based his opinion that the Browning weapon recovered on Townsend Street was used in the Orchard Street shooting based on a comparison of the class characteristics and individual characteristics of the casings found on the street with the test-fired casings from the firearm. He admitted that there have been changes in the science of firearm and toolmark identification since the trial.

Stephenson testified at the hearing that it is now understood that subclass characteristics are a potential source of false identifications. He said an examiner could erroneously attribute a microscopic marking on a bullet or casing to be individual to a specific firearm when in fact it is attributable to a manufactured lot of firearms. As a result, he said, a firearm examiner needs to be careful to distinguish between individual and subclass characteristics. The examiner would need to be familiar with the manufacturing process of the weapon in order to perform the analysis, a familiarity that Stephenson said he lacked.

He said that he had not made a differentiation between individual and subclass characteristics in his examination of the fired casings. Stephenson admitted that, based on the new understanding of subclass characteristics, his opinion that the Browning firearm was the source of the 810 Orchard Street shell casings would no longer be valid today.

The judge also cited the evidentiary hearing testimony of William Tobin, a research metallurgist and a former member of the forensic metallurgy operations at the FBI Laboratory. Tobin testified that, since Carmon’s trial, “a consensus has emerged within the relevant scientific community that the practice of opining that a particular projectile or casing was fired by a particular firearm lacks foundational validity, both scientifically and experientially.”

The judge said Carmon’s conviction rested on three main pillars—the evidence that a firearm connected to him was the gun used in the shooting and his identifications by Stanley and Jones.

“Each of these pillars has been splintered by the persuasive force of the new evidence,” Judge Alander declared. “Suppressed exculpatory evidence supports a third-party culpability claim that Brantley and Little were responsible.”

On December 12, 2022, Carmon was released on bond. On June 13, 2023, the prosecution dismissed the charges.

In July 2023, Carmon filed a federal lawsuit seeking compensation for his wrongful conviction.

– Maurice Possley

|