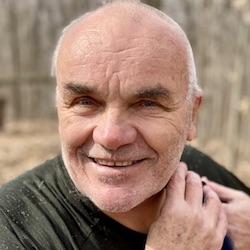

Jeff Titus (Photo: Ken Kolker/WOOD TV8)

Brown, Estes, and a friend, Mark Perry, had entered the game area in the late afternoon—the best time to hunt for deer—and then split up to hunt. Brown would later say he casually made his way toward the location where he believed the shots were fired, believing he would find Estes and freshly killed deer.

Instead, Brown found Estes and another man, 37-year-old Jim Bennett, lying on the ground several feet apart. Both had been shot in the back at close range, apparently with a shotgun. Both were dead. Bennett’s weapon, a muzzle loading rifle, was on the ground, but Estes’s 12-gauge shotgun was nowhere to be found.

Darkness fell as police arrived. An initial search was unsuccessful. The lights set up attracted the attention of 38-year-old Jeff Titus, whose farm bordered the game area. Police were still on the scene when Titus and a friend, Stan Driskell, drove up from Titus’s property. Titus said that he and Driskell had just returned from hunting on property about a 35-minute drive north of the game area.

Two days later, on November 19, 1990, Titus called police and reported that he had found a shotgun on the edge of the game area. Titus was a trapper and said that while checking his traps, he spotted the gun.

Detectives were stymied in their investigation of the crime. They looked into the possibility that drugs were involved somehow. Bennett covertly grew marijuana and Estes allegedly had once proposed ripping off Bennett’s marijuana. But how and why both men wound up murdered that day remained a mystery.

The only possible suspect appeared to be a man whose car had gotten stuck in a ditch near the game area not long after the shots were heard. Brown told police that he had heard squealing tires in the distance after hearing the gunshots. A witness told police that the man in the ditch was sweating and refused an offer to call police for help. A man passing by in a truck had pulled the car out and the driver sped off.

The murders remained unsolved for a decade. In 1998, a cold case squad was formed by the Kalamazoo police department, and in 2001, the unit turned its focus on the murders of Estes and Bennett.

On December 12, 2001, the investigation concluded with the arrest of Titus, by then 49 years old. In addition to his farm, Titus ran an animal control business that he had developed when the economics of his trapping business soured. He was charged with two counts of first-degree murder and two counts of using a firearm to commit a felony.

In July 2002, Titus went to trial in Kalamazoo County Circuit Court. The prosecutor, Scott Brower, portrayed Titus, a former Marine and former security officer at the Veterans Affairs (VA) Hospital in Battle Creek, Michigan, as a vengeful property owner who had threatened people who came onto his property from the Fulton game area in the past.

Brower, in his opening statement to the jury, said that other hunters would testify about confrontations with Titus, who had purchased the farm in 1990, just a few months before the murders. “You will find these witness accounts so remarkably similar that the only reasonable conclusion would be that he was the one that confronted Doug and Jim in the same area, in the same manner as the others, and that confrontation escalated into murder.”

The prosecutor’s characterization was telling—there was no physical or forensic evidence linking Titus to the crime. The prosecution theory was based on a constrained view of events. At the time of the crime, Titus had said that he and his friend, Driskell, had spent the day hunting on the properties of two farms north of the Fulton game area. The prosecution contended that while Titus and Driskell were hunting separately, Titus left on his own, drove to his farm, spotted Estes and Bennett, confronted them about hunting on his property, and killed them.

For the first few days of the trial, the prosecution’s evidence was a steady stream of people who had worked with Titus at the VA hospital as well as neighbors and others who hunted in the area. Their testimony had two primary themes: Titus was territorial and confronted hunters who wandered onto his property, and he often spoke of Estes and Bennett, the hunters killed near his property line, and did so in ways that were unnerving.

Bonnie Huffman testified that in 1990, prior to the murders, Titus had confronted her while she was hunting on her parents’ farm which was adjacent to Titus’s farm. She said that Titus was waving a pistol around, told her she was on his land, and told her to get out. She said the incident had so scared her that she never hunted in that area again, even though she knew it was not on Titus’s property.

On the day of the murders, according to Huffman, she had just come in from hunting on the farm when Titus drove up at about 5 p.m. Huffman said that Titus said he had just found two dead bodies on his farm. Huffman testified that she did not hear the sirens of emergency vehicles until after Titus had reported finding the bodies. She told the jury that she came forward after Titus was charged because she heard that he had told authorities he didn’t come home from his day of hunting until after dark. “It upset me because he followed me into my mom and dad’s house,” Huffman said. “And that was before dark.”

Huffman also testified that earlier that afternoon, she heard the squealing of tires and a car engine revving. She said she walked out of the thicket she was in and saw a car in the ditch. She said she climbed over the fence and asked the driver if he wanted help. “This gentleman wanted no help whatsoever, which to me was very strange in the country because you just don’t turn down help when you [get] help offered out there.”

Richard Adams testified that he was bow hunting for deer in the game area in late September or early October 1990. He said he was in his hunting blind when Titus approached, holding a shotgun. Titus claimed the blind was on Titus’s property. Adams said, “He was…a very angry gentleman, very forceful. He wanted me off the property…now….he had his hand near the trigger and just kept waving it around—loosely waving it around. I mean if the safety had been off, if he’d squeezed the trigger, I could have been shot.”

Sixteen-year-old Chris Whitby testified that he, along with his stepfather and two uncles, was hunting in the Fulton game area in 1991—the year after the murders. He said he shot a deer and tracked it into a cornfield adjacent to the game area. He said he was walking out of the cornfield when Titus walked up to him and “asked what I’m doing on his property. I explained to him. In the meantime, he’s got a gun pointed towards my direction…We started having a few words.” At that moment, his uncles and stepfather were about 50 yards away and approaching because they heard yelling. “They asked him what the hell…he was doing having a gun pointed at my direction.”

“He [Titus] said he’d been having a lot of problems, I guess, with hunters going on his property and trespassing,” Whitby testified. “If he was to catch me on his property again, he’d take it in with the law.” Whitby said Titus was holding a shotgun “in an area if it would have went off, it would have hit me.’

“I was scared,” Whitby said. “I mean if someone walks up, you know, and starts pointing a gun, you know, towards their direction. Any hunter’s going to be scared. I don’t care who you are.”

Whitby’s father, Ted Whitby, also testified about the incident. He recalled that he heard shouting, followed the sounds and came upon Chris. Titus, he said, had a shotgun “waist high aimed at Chris.”

Titus, he said, was “ornery, pissed off, and [had] a bad attitude. And, you know, remarks was exchanged; and I told Chris, ‘Come on, let’s get up out of here.’”

Marley Dale Beaty testified that two or three years after the murders, he was hunting in the Fulton game area, sitting in his favorite hunting spot when Titus, carrying a shotgun, approached. “He said that he owned all the adjacent land around him and his buddy, they wanted to hunt it all…he wanted me to leave,” Beaty said. “And he said, you know, guys are known to be shot out here in the woods.”

Beaty said, “The way he was looking at me, you know, and the way he had his gun over his arms—Well, I’ll just tell you, he scared me; so I flipped my gun off safety…where he could hear it. And I told him that shit works both ways, get the hell away from me. And he stood there for a minute and then he walked off.”

Michael Finn testified that he had worked at the VA hospital as a fellow officer with Titus. He told the jury that Titus had recounted finding the shotgun and that Titus claimed he cleaned the gun and then called police.

John Kalikin, who was Titus’s supervisor at the VA, testified that, in 1992, Titus told him about finding the gun, cleaning it, and holding onto it for a couple of days before calling the police. “He felt [the police] had insulted him during the course of the investigation that they had conducted and it was his way of getting back at them,” Kalikin testified.

Marian Beardsley-Gibbs testified that she worked at the VA as a coordinator of homeless programs. She said that four or five days after the murders, Titus talked about finding the shotgun and how poorly the search had been conducted. She said Titus also described the positions of the bodies. She said Titus “became very flushed and sweaty and just talked faster and faster to the point…we couldn’t have a conversation…he seemed to get really agitated.”

Beardsley-Gibbs said Titus claimed to have kicked Estes and Bennett off his land prior to the murders, calling them “sons of bitches.”

Daniel Israels testified that on November 29, 1990, 12 days after the shooting, he was at a deer reporting station at the Fort Custer training center in Augusta, Michigan following a hunt. At the station, he saw Titus, who was also reporting deer that he had shot. Israels testified that Titus claimed to have been at home on his farm and heard the gunshots at about 4:30 p.m. Israels testified that Titus reported that both victims had been shot in the back and close range.

Michelle Smock, another VA employee, testified that during a conversation in 1992 or 1993 with Titus, he talked about the shooting. She said he “just said that they deserved it for being on his property because they were trespassing.” During cross-examination, Smock described Titus as a talkative man who exaggerated and was a braggart.

Amy Branham was a secretary at the VA hospital. She testified that in early 1993, Titus “mentioned to me that there were two dead hunters found on his property and that they were trying to prove that he did it, but there was no way that they could prove it.” She said he laughed as he said it, “at which time I became very uncomfortable.”

Donna Hutchins, another VA employee, said a couple of weeks after the murders, Titus was outside on a smoke break when she took a patient out. “I distinctly remember him saying that he would have no problem—no qualms whatsoever about shooting someone if they were on his property.” She said she was “kind of astounded…I felt that…he meant it that he would…He said he would have no problem whatsoever shooting someone in the back if they were on his property.”

The prosecutor asked, “Did he make any statements about how he felt that the hunters were dead?”

“He was excited about it,” Hutchins testified. “They were on his property and that’s what they deserved….I said, ‘You did this.’ And he said, ‘Probably,’ and was smirking and like—I don’t know how else I can say, but like smart alecky. It was like cool; it makes him more manly to me.”

Hutchins said that was the last time she had contact with Titus. “I was afraid of him,” she said.

Hutchins conceded on cross-examination that Titus was considered a braggart, particularly in his conversations with women. However, on that occasion, she said, “I sincerely believed he was telling the truth.”

There were other witnesses from the VA. One testified that Titus described the victims as “poachers.” Another said that Titus complained of having difficulty sleeping, saying, “The ghosts are back.”

Marcia Alcook, who helped organize the deer hunt at Fort Custer, testified that Titus told her that if he caught a poacher, he would “skin them alive and pour salt on their bodies.”

Guy Cherry testified that he was in the Army National Guard in Battle Creek and that Titus would occasionally stop in. He said that in 1991, when Cherry expressed an interest in getting a gun to take up hunting, Titus said “that he’d catch a lot of people on his property all the time and he could confiscate [a gun] and grind down the serial number and sell it to me pretty cheap.”

Cherry said that Titus said that “if anybody ever gave him a problem that he would have no problem blowing them away. He’d just tell the cops they drew first.”

Rodney Clute, a wildlife biologist for the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, testified that part of his job duties was to inspect crop damage due to wildlife. He said that in the fall of 1991, nearly a year after the murders, he visited Titus’s farm to inspect for crop damage. Clute said Titus volunteered that he was a “prime suspect” in the murders and that Titus’s supervisor believed Titus was guilty.

Clute said he was surprised by the comments. “And I was also rather surprised by the way he stated it. The only term I could use was pride,” Clute said. “It was almost like he was proud of the fact that he was a suspect.”

Marty Johnson, a Kalamazoo County Sheriff’s deputy, testified that he was in charge of the forensic science laboratory and evidence technician unit. He said he went to the scene and saw that the bodies each had a shotgun wound in the center of the back that had exited their chests.

Johnson said that Bennett’s muzzleloader was examined for fingerprints. Two prints belonged to Bennett, the owner of the gun, and a third was not identifiable due to insufficient characteristics. Johnson said the gun that Titus found also was examined, but no prints were found. The prosecutor asked if the lack of fingerprints would be consistent with the gun being wiped clean prior to or after handling.

“Being wiped clean would be one explanation why latent prints would not be recoverable,” Johnson said.

Johnson testified that Estes had been killed with a single shotgun slug and that Bennet had been killed with shotgun pellets.

Detective Michel Werkema testified that during the investigation, Titus was interviewed and denied committing the murders. Titus said that he and his friend, Stan Driskell, hunted on the farm of Larry Crandall during the morning of the day of the murders and on the adjacent farm of Gerald and Eloise Shepard in the afternoon. Titus said he shot a deer, but did not gut it in the field, as was customary, because he intended to take the deer back to his farm and use the entrails to bait his traps. He said that he and Driskell returned back to Titus’s farm after dark and saw the lights from the crime scene.

Ron Petrowski, a Portage, Michigan, police officer, testified that he drove from the Shepard farm to Titus’s farm several times. He said the trip took about 35 minutes.

Michael Brown, a Kalamazoo County Sheriff’s detective, testified that he interviewed Titus about the statements made by VA workers. Brown said Titus denied making the statements.

Titus did not testify. His defense lawyers called Driskell, who testified that he and Titus went hunting that day on the Crandall and Shepard farms. He admitted they did not hunt together and that most deer hunters split up to hunt in solitary. While he testified to meeting Titus at the end of the day, Driskell said he could not say where Titus was during the time they were apart. Driskell said he had been hunting with Titus for nearly 10 years at that point and never knew Titus to leave the forest prior to dark.

Larry Crandall testified that Titus and Driskell hunted on the Crandall dairy farm on the morning of the day of the crime. Crandall said he had known Titus since he was teenager when Titus had worked on Crandall farm.

Paul Frederick testified that he met Titus while Frederick was a counselor at Pennfield High School in Battle Creek and Titus was a junior. Over time, they began hunting together and hunted for many years. Frederick said that Titus never hunted deer with shotgun shells loaded with pellets—only slugs. Frederick said that Titus had a 12-gauge shotgun that had a smooth bore barrel that Titus later replaced with a rifled barrel. Frederick said no hunter would use pellets in a gun with a rifled barrel. Asked whether Titus ever used alternating loads—one shell with a slug followed by a shell loaded with buckshot, Frederick said that if he had caught Titus doing so, he would have berated him. “I don’t believe in it,” Frederick testified. “I always told him if you can’t hit a deer with a slug, you don’t have any business shooting [buck]shot.”

Helen Nofz testified that she lived across the street from the Fulton game area. She recalled that on the day of the murders, a neighbor called and reported a car in the ditch at the corner that needed help. She said she drove to the ditch and found the car “nose down in the ditch…he wanted someone to pull him out.” She offered to call the police and get a tow truck.

She said the man whose car was in the ditch “got very agitated and said he did not want to call the police.” She said at that moment, a truck pulled up. “The gentleman in the truck said he’d pull him out of the ditch, so I went home.” She said the man was sweating and nervous, and that when she heard later about the murders, she called the police. “I felt that it might be related somehow,” she said.

Nofz testified that prior to Titus’s trial, she viewed a photographic lineup presented by a defense investigator. She identified one of the photographs as looking “quite like” the man in the ditch. The photo was of Charles Dean Lamp.

Prior to the presentation of evidence in the trial, the defense told the trial judge, Philip Schaefer, that a prison inmate had told them that Lamp, who was serving time in prison, had admitted to the murders. However, when the defense sent an investigator to interview Lamp, he denied involvement. This evidence was not presented to the jury.

During his closing argument, prosecutor Brower portrayed Titus as a man so obsessed with his property that he left the woods where he was hunting with Driskell, drove home, confronted and killed Estes and Bennett, then drove back to meet up with Driskell at the end of the day.

On July 19, 2002, the jury convicted Titus of two counts of first-degree murder and two counts of using a firearm to commit a felony. He was sentenced to life in prison without parole.

The Michigan Court of Appeals upheld the conviction in February 2004. The Michigan Supreme court denied permission to appeal in November 2004. Titus filed a federal petition for a writ of habeas corpus in February 2006. The petition was denied in 2009 and the denial was upheld by the Sixth Circuit U.S. of Appeals in 2011.

In 2013, the Michigan Innocence Clinic (MIC), at the University of Michigan Law School, accepted Titus’s case on the recommendation of Bruce Wiersma and Royce Ballett, who were detectives assigned to the case right after the murders. At the time, both detectives were convinced that Titus’s alibi was solid based on their interviews of Larry Crandall and Gerald and Eloise Shepard. They had cleared Titus of involvement in the crime.

In August 2014, MIC filed a petition for relief from judgment. The petition cited evidence pointing to Titus’s innocence, including:

--Huffman’s initial report to police said nothing about Titus coming to the farm at 5 p.m., before the murders were reported. Huffman’s mother, Patricia Burnside, initially reported to police that Titus arrived around 8 or 9 p.m. that night.

--Gerald Shepard and his wife, who did not testify at the trial because they were “not of sound mind” at that time, had verified Titus’s presence on their farm during interviews with Wiersma and Ballett, both of whom could have been called as witnesses at trial. Soon after the murders, Gerald and Eloise Shepard had signed a statement saying that they knew Titus was on their farm until dark because they saw him drive his truck out of the driveway with a deer.

--Less than a month after the murders, Titus had taken a polygraph examination and had been deemed to be truthful when he denied involvement in the crime.

--When Titus became the focus of the cold case investigation, Detective Richard Mattison told the team that the evidence indicated there were two gunmen, not one. He based that conclusion on the location of the bodies, the fact that one was shot with a slug and the other with buckshot pellets, the angle of the entrance wounds indicating they were shot directly from behind, and the unlikelihood of Titus being able to complete a roundtrip and the murders and still be back on the Crandall farm. The petition asserted that the prosecution had failed to disclose Mattison’s conclusion.

In March 2015, an evidentiary hearing was held before Judge Alexander Lipsey. Ballett and Weirsma both testified that they believed Titus’s alibi was truthful based on their interviews with the Crandall and Shepard families. Mattison testified about his belief that there were two shooters and how his conclusions had been rejected by the cold case squad.

John Nixon, a mechanical engineer, testified that based on his review of the crime scene photos and the autopsy evidence, the existence of two gunmen was “more plausible.”

In April 2015, Judge Lipsey denied the petition. He said that while Mattison’s conclusion was not disclosed to the defense, he would not rule on whether it was a violation of the requirement that prosecutors disclose exculpatory evidence. The judge said that not only would the “theory’s persuasive impact be somewhat deflated by the testimony of every other member of the investigative team of which Mattison was a member, but that reduced impact would have then been juxtaposed with the substantial inculpatory evidence” from “well over a dozen individuals” who described ”frightening encounters” with Titus in which he either threatened them with a firearm in the same area as the murders or discussed the killings in such a way as to prompt the listeners to suspect his guilt.

In 2018, Titus filed another federal petition for a writ of habeas corpus. In 2019, while that case was pending, producers Jacinda Davis and Kevin Fitzpatrick teamed up with Investigation Discovery, a true-crime television program, to re-investigate the case. Ultimately they collaborated with Susan Simpson’s podcast, Undisclosed, to present a compelling portrait of Titus’s innocence. As part of that re-investigation, Huffman said that Titus came to the farm about 8 p.m. When asked about her trial testimony that Titus was there as early as 5 p.m. on the day of the murders, Huffman said she only remembered one thing about the trial—that she had complimented Titus on his necktie.

Perhaps most significantly, they learned about Thomas Dillon, a serial killer convicted of killing multiple hunters and outdoorsmen. He had been arrested in 1993 and had pled guilty to five counts of first-degree murder in Ohio to avoid the death penalty. He also was a suspect in an unsolved murder of an outdoorsman in Pennsylvania. They filed public record requests for documents in Ohio.

In the documents they obtained, Simpson and Davis learned that while in prison, Dillon told a cellmate that he once killed two hunters who were standing close together in a county where no one could prove Dillion had ever been. The cellmate later signed an affidavit for the MIC.

Subsequently, MIC director David Moran discovered a file of about 30 pages on Dillon labeled “Serial Killer” in the Kalamazoo County Sheriff’s files on the Estes/Bennett murders.

The file contained Ohio police reports showing that Dillion had borrowed two guns from two co-workers to go hunting on November 17, 1990, the day of the murders. He returned the guns later, but failed to return the barrel of one of the weapons, saying he had inadvertently thrown it away.

The file showed that Dillion had registered a deer kill in Ravenna, Ohio at 11:20 a.m. on November 17.

Moreover, Helen Nofz was taken to Ohio where she and her son, who had accompanied her to the ditch on the day the car was stuck, both viewed Dillion in a lineup. Both identified him as the man in the car in the ditch. At the time of the crime, Nofz had given a description of the car, which resembled a car that belonged to Dillon’s wife.

However, despite the identification, police had cleared Dillon of involvement in the slaying because of a miscalculation. Police had estimated that Dillon would not have had enough time to drive from Ravenna to the Fulton game area. In fact, Dillon could have driven there in enough time to commit the murders.

In September 2019, the federal court put Titus’s federal habeas case on hold while the Michigan Attorney General’s Conviction Integrity Unit (CIU) could conduct an investigation. The CIU ultimately collected more information, including that the FBI had conducted surveillance of Dillion and documented occasions when he would drive hundreds of miles from home. In addition, Dillon picked up his shell casings and left no evidence at any of his murder scenes.

One of his killings occurred on November 10, 1990, one week before Estes and Burnett were killed. And he killed another deer hunter on November 28, 1990, 11 days after the murders.

On February 22, 2023, the CIU filed a stipulation to the pending habeas petition outlining the newly discovered evidence about Dillion, and agreeing to a new trial and to Titus’s immediate release.

A companion filing by the MIC noted that at the time of the crime, Nofz had helped police create a composite sketch of the man in the ditch. The sketch “bears a striking resemblance to Thomas Dillion,” the filing said.

The filing noted that Dillon had borrowed one gun from a co-worker which had two interchangeable barrels—one for buckshot and one for slugs. Dillion failed to return the buckshot barrel. “The use of two different shotguns is consistent with the theory that Mr. Estes and Mr. Bennett were killed using two types of shotgun ammunition,” the filing said.

Dillion had died in prison in 2011.

On February 24, 2023, U.S. District Judge Paul Borman granted Titus’s writ of habeas corpus and vacated his conviction. Titus was released later that day, more than 20 years after his conviction.

On June 1, 2023, Kalamazoo County Prosecutor Jeff Getting agreed to dismiss the charges.

The 71-year-old Titus declared, “All I can say is, I’m an innocent man. I am glad to have this off of my head and that I can get on with my life. I have no hard feelings cause it doesn’t help me to let that eat at me.”

Titus was awarded $1 million in compensation by the state of Michigan in August 2023. In September 2023, he filed a $100 million federal civil rights lawsuit against detectives Werkema and Brown.

– Maurice Possley

|