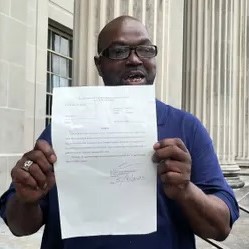

Patrick Brown, with the court order granting him freedom. (Photo: The Guardian)

The girl and her family lived in New Orleans, Louisiana, and the grandmother initially believed the problem was because the girl had not bathed before going to bed on Mardi Gras, which was the previous day.

The grandmother picked the girl up from school on February 17 and was told the child had cried most of the day as if she had a stomachache. The grandmother gave the girl some medicine and called her mother, Cathy, and said the girl needed to see a doctor.

The girl generally stayed with Patricia during the week. Cathy came by the next day and saw that her daughter had a greenish-yellow vaginal discharge. She took the girl to Charity Hospital, where she was given Lotrimin and told to return on Monday. The girl spent the weekend at Cathy’s house. The other residents included Cathy’s father, Cathy’s cousin, and Cathy’s partner, 20-year-old Patrick Brown, whom the girl considered to be her stepfather.

The girl returned to the hospital on Monday, February 21, now accompanied by a great-aunt, Carolyn. A pediatric resident, Dr. Ronald Wilcox, examined her and inspected the girl’s vaginal discharge. He suspected that the girl had a sexually transmitted disease, either gonorrhea or chlamydia, and asked Dr. Maria Mena, a pediatrician who worked with the hospital’s Child Sexual Abuse Clinic, to join him. Carolyn called Patricia, who came to the hospital.

Mena arrived and said that it appeared the girl had an STD and that an assessment for possible sex abuse was necessary. The doctors asked the girl if anyone had ever touched her “down there.”

According to the doctors, after some prompting and assurances of her safety, the girl began to cry and said, “My daddy Patrick stuck his penis in me down there.”

The doctors later performed a pelvic exam, which they said revealed evidence of vaginal penetration “a couple of weeks earlier.” In addition, swabbed samples taken from the girl tested positive for the bacteria that causes gonorrhea.

Following the medical examination, two detectives with the New Orleans Police Department spoke with the girl at the hospital. They then interviewed Patricia.

By now, Brown and Cathy had arrived at the hospital. The detectives advised Brown of his rights, and he and Cathy went with the officers to the police station for more questioning. Brown denied he abused the girl or Cathy’s other children, stating that he was rarely left alone with them. He was then arrested and charged with aggravated rape. Child Protective Services removed the girl from the home and placed her in the custody of Carolyn, the great-aunt.

Cathy initially believed Brown’s denials. She accused her cousin and her father of molesting the girl. Both men were tested for STDs at a local clinic. The cousin’s test, dated February 24, revealed a yeast infection. The father’s test, dated February 28, was negative. Brown was tested on March 25, and at trial it was stipulated that he “previously had a gonorrhea infection.”

Brown’s trial in Orleans Parish Criminal District Court began on December 13, 1994. Wilcox testified about his notes from the girl examination and said that nobody mentioned the words “Patrick” or “penis” prior to the girl’s statements. He said he did not ask leading questions.

By the time of the trial, Cathy no longer believed in Brown’s innocence, but she testified as a witness both for the state and for Brown. Cathy testified that the girl was raised mostly by Carolyn and Patricia, and that the girl sometimes called the women’s boyfriends “Daddy.” She said she had never heard the girl refer to Brown as “Daddy Patrick.” She testified that she had initially accused her father of abusing the girl because he would get drunk at night and Cathy would find him in the morning “in the bed next to my children.”

By now, the girl was 7 years old. Outside the presence of the jury, she answered preliminary questions from the court and the attorneys about her competency. When the jury was brought in, the girl began to cry and her nose began to bleed. She was removed from the courtroom, and Judge Morris Reed told the jurors not to be influenced or “distracted” by the incident.

The prosecutor then recalled the girl to the witness stand. He asked her a series of opening questions and whether she knew the difference between the truth and a lie. When the prosecutor asked the girl about the consequences of telling a lie, the girl was unable to answer. Her nose began to bleed again. She was again removed from the courtroom. The state sought to recall her, but Judge Wood ruled against the request, citing the potential prejudice of further “dramatics.”

On December 15, 1994, the jury convicted Brown of aggravated rape. He received a sentence of life without parole.

Brown appealed his conviction, arguing that there was insufficient evidence, and that Judge Wood should not have allowed Wilcox to give hearsay testimony about the girl’s alleged statements because it violated his rights to cross-examine his accuser. He also said that Judge Wood should have declared a mistrial after the girl’s two false starts on the witness stand.

Although hearsay testimony derived from statements related to medical treatment is generally allowed, Brown argued that this situation was different. He argued that there was no evidence that the girl understood the questions from the doctors and that the girl made the statements after being prodded by Patricia and Carolyn, who had their own reasons for pointing the finger at Brown. (At trial, Patricia testified that she did not like Brown; Carolyn’s son was the cousin who lived with Cathy and Brown.)

The Louisiana Court of Appeal for the Fourth Circuit affirmed Brown’s conviction on October 6, 1999. It said that cases involving child victims allowed exceptions to the hearsay rule and that Judge Wood’s instructions to the jury on the girl's lack of testimony and her nosebleeds cured any potential prejudice Brown suffered.

Brown later filed other motions for relief, which were denied. In 2021, Louisiana amended its state laws on post-conviction relief, allowing defendants to make new claims based on factual innocence.

Brown filed a motion for a new trial on February 9, 2022, at the same time asking the Civil Rights Division of the Orleans Parish District Attorney to review his conviction. He was now represented by Kelly Orians, a professor at the University of Virginia School of Law who heads the school’s Decarceration and Community Reentry Clinic. Previously, she had extensive experience in criminal-justice issues in New Orleans.

After conducting its own investigation, the district attorney filed a response asking the court to vacate Brown’s conviction. The response said that the girl had through the years made numerous efforts to tell officials that Brown wasn’t the man who raped her.

“She has been discounted and ignored every time she has tried to correct this injustice,” the response said. “When the girl contacted this administration, we immediately reviewed the case. As a result of that review, the State has concluded that Mr. Brown meets the standard for post-conviction relief based on clear and convincing evidence of his innocence.”

Since 2002, according to the state’s response, the girl had been saying Brown wasn’t the man who raped her. She had told prosecutors on at least three separate occasions that Brown was not the man who raped her.

In 2015, the girl signed an affidavit stating that her mother’s cousin was the assailant. The state’s response said the cousin’s test results should have been a red flag, as he tested positive for a yeast infection frequently caused by gonorrhea.

The cousin’s possible involvement was well-known at the time of the trial. Notes in the district attorney’s files quoted the cousin as saying, “That’s why your man is taking another [man’s] charge. I [had sex] with your daughter.” He made similar comments at least twice more, according to the files.

“The gist of this information was disclosed to the defense before trial, but its relevance was not fully appreciated while adults still believed the six-year-old claimed that Patrick Brown was the person who raped her,” the response said.

The girl did not testify at trial, the response said; she was anxious and knew something was not right. “The physical and circumstantial evidence from the time of the investigation fully corroborates the version of events and the identity of her rapist that she has been telling since she was fourteen years old,” the response said. “This is not a case of recanting sworn testimony given to a jury; this is a case of finally listening to a woman who, for over twenty years, has been telling the State that the wrong man is in prison.”

On May 8, 2023, Brown and the girl appeared in a courtroom before Judge Calvin Johnson. The girl testified that she had written more than 100 letters to prosecutors and court officials telling them of their error.

Johnson vacated Brown’s conviction. The state dismissed the charge.

“Thank you for listening, finally,” the girl said. “Thank you for hearing me. Thank you for helping me tell the truth. Thank you for helping our family heal. Thank you for giving me my dad back.”

In February 2024, Brown filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against the Orleans Parish District Attorney's Office seeking compensation for his wrongful conviction. Brown also filed a claim for compensation from the state of Louisiana.

– Ken Otterbourg

|