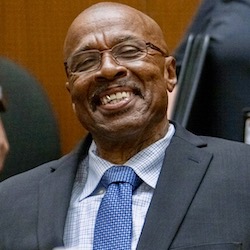

Maurice Hastings (Photo: J. Emilio Flores/Cal State LA)

Paxton later said they did not meet.

And she never came home.

In the early morning hours of Monday June 20, 1983, Roberta’s white 1981 Cadillac, with its personalized license plate—MS RW 1—was found ablaze in an apartment building parking space several miles away in Inglewood, California. When the fire was extinguished, Roberta’s body was found in the trunk. She had been shot once in the head. The .38-caliber bullet was found under her body.

Billy had been frantically looking for Roberta since the moment he woke up on that Sunday morning at about 6:30 a.m. He had gotten up from the couch, where he had fallen asleep, and when he checked the bedroom, he saw it was undisturbed.

Not long after, he got a phone call from a man who said he had found Roberta’s wallet in his front yard in Inglewood, about eight miles from Billy’s home. When Billy retrieved it, the wallet was missing $500 in cash. Also missing was Roberta’s telephone calling card which bore the personal identification number so that anyone with the card or the calling card numbers could make calls.

Billy called the Los Angeles police to file a missing person’s report, but was told to call back after Roberta had been missing for 48 hours. By 9 a.m., Billy had arranged for a ride with 22-year-old George Pinson, the son of a woman who was a tenant in the Wydermyer home. They began to drive around in hopes of finding Roberta. Later that morning, they were on 108th Street, facing east at a traffic light at the intersection of Crenshaw Boulevard, when Billy spotted Roberta’s car cruising north on Crenshaw.

They followed the car, and a few blocks later, pulled up along the driver’s side. Billy saw a Black man wearing a black and white baseball cap bearing the letters L.A.P.D. Believing the driver was a Los Angeles police officer, Billy asked, “Where is the lady that drives this car?”

Billy would later testify, “He looked and me and smiled and turn[ed] his head…and said, ‘She’s down at 106th and Normandie, man.’” Billy realized the man was not a police officer, and at the same time, the man sped off in Roberta’s Cadillac.

After several twists and turns, speeding up and down side streets, the Cadillac came to an abrupt halt in an alley. The driver turned around in his seat. Holding a revolver in both hands, he fired several shots. The bullets shattered the rear window of the Cadillac and tore through the windshield of Pinson’s Chevrolet Malibu. One bullet struck Wydermyer near his left temple. Another came to rest in the back seat. A third wound up on the dashboard.

Pinson sped away and took Wydermyer to a hospital where he underwent surgery to remove bullet fragments. One fragment, lodged near his brain stem, was not removed for fear of causing brain damage during surgery. Pinson was treated for glass fragments in his eyes.

At about 1:15 a.m. Monday morning, a police officer on patrol drove down the alley behind 10223 South Woodworth Avenue in Inglewood. He saw smoke and discovered Roberta’s Cadillac with the front and rear passenger seats ablaze. The car was backed into a parking space. When the blaze was extinguished, police checked the license plate, popped open the trunk, which had not been burned, and found Roberta dead of a single gunshot wound to the head.

During an autopsy, a rape kit was prepared, including swabs and slides. At trial, a deputy medical examiner testified that there were no powder burns, suggesting that the fatal bullet was fired from a distance of at least two feet away.

Several mysterious calls were made to the Wydermyer home. The first one came in around 2 a.m. not long after the car was found. The caller used the name “Billy,” which raised suspicion since his friends knew him as “Touché.” The caller wanted to know why Billy had been chasing him and said, “He made a big mistake.”

After several more calls came in during which the caller did not speak, police set up a phone tap to try to trace the calls. The following day, June 21, a caller asked if Billy was still alive. The call was traced to a public telephone at Montclair Liquors in Long Beach, California.

On July 18, 1983, the bill for Roberta’s telephone calling card arrived and showed that 20 calls were made using the card between June 21 and June 29. Eight calls were made later, but didn’t show up until the next bill arrived. Police began interviewing recipients of the calls, whose numbers appeared on the bills. They learned that the person making the calls was 29-year-old Maurice Hastings, whose sister lived near Montclair Liquors. Some of the calls were made to women in Pittsburgh, all from public phones and many in bus stations beginning in Los Angeles, then New Mexico, Phoenix, and Oklahoma City.

None of the calling card calls were made to the Wydermyer home, leaving investigators to speculate on the source of the calls to Wydermyer's home. Prosecutors would later argue that because some of the calls made on the calling card were made from the pay phone at Montclair Liquors and at least one of the calls to the Wydermyer home was made from that liquor store pay phone, Hastings must have been the person calling the Wydermyer home.

Police tracked Hastings to several locations in Pittsburgh, but were unable to find him. They finally caught up to him on October 2, 1984 at his mother’s house in Los Angeles. He was charged with capital murder, robbery, and attempted murder of Pinson and Billy Wydermyer.

In 1986, Hastings went to trial in Los Angeles County Superior Court. The prosecution sought the death penalty. After several weeks of trial and eight days of jury deliberation, a mistrial was declared when the jury deadlocked, voting 10 to 2 to convict Hastings.

He went to trial a second time in April 1988. The prosecution again sought the death penalty.

Wydermyer and Pinson both identified Hastings as the man who had been driving Roberta’s car and who fired shots at them when they pursued him.

Yolanda Spears, a resident of the apartment building behind which the Cadillac had been found ablaze, testified that she took her boyfriend to work on the afternoon of June 19, 1983. She said when she came back and tried to park in her spot, the Cadillac was there, facing inward. She testified that Hastings could have been the man who was in the driver’s seat. She said she parked on the street and later that evening went to pick up her boyfriend. When she returned at about 11:30 p.m., the Cadillac was still in the space, but was backed in. The car was ablaze less than two hours later. Asked if she saw the man in court who was in the car, Spears first said, “Maybe.” She then identified Hastings.

Another resident of the building, Linda Toler, testified that at about 11 p.m., she saw Hastings walking rapidly away from the rear of the building.

All four witnesses testified that they saw a gold tooth or a glint in Hasting’s mouth. Hastings did have a gold tooth.

A deputy medical examiner testified that Roberta died of a gunshot wound to the head. A Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department criminologist testified that the bullet recovered from the trunk of the car and the bullets found on the dashboard of Pinson’s car had been fired from the same .38-caliber revolver.

Although semen and sperm were found in the rape kit, the amounts were too small to be examined to determine blood type, forensic analysts testified. Attempts to lift fingerprints from Roberta’s wallet only produced one legible print, which belonged to Roberta.

No physical or forensic evidence linked Hastings to the crime.

The prosecution relied heavily on the phone records to argue that on June 26, 1983 Hastings had “skipped town,” heading for Pittsburgh. One witness, Jo Ann Austin, testified that she met Hastings at the Los Angeles bus station that night. She was heading to Portland, Oregon, to see her mother. She said Hastings was heading to Pittsburg.

Austin testified that in August 1983, Hastings told her that a friend of his had given him the phone calling card and that it had been taken from a lady who was “knocked off.” Austin testified that Hastings told her that police were looking for him and advised her not to say anything to police.

The prosecution presented evidence that in Pittsburgh Hastings had pawned a gold pendant containing nine diamonds for $225. The description of the pendant, which Hastings later redeemed and was never recovered, was similar to a pendant that Roberta was wearing the night she was killed.

The defense contended that Hastings was at a party the night that Roberta was killed and introduced numerous photographs allegedly taken at the affair—some of them showing Hastings. The photographs did not bear a date, and one witness testified the party was in 1984—not 1983 when the murder occurred.

Hastings’s sister, Carleen, testified that a man named Donald Sanford gave her the stolen credit card numbers for the calling card and that she had given them to Hastings.

On July 7, 1988, the jury convicted Hastings of capital murder and robbery of Roberta and attempted murder and assault with a firearm of Pinson and Billy Wydermyer. The jury rejected the prosecution’s plea to impose the death penalty and voted to sentence Hastings to life in prison without parole.

In 1994, the Second Appellate District of California upheld his convictions and sentence.

Ultimately, Hastings began writing letters and filing motions, acting without a lawyer, seeking DNA testing of the rape kit.

In 2000, Hastings wrote to the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office. “I have been incarcerated for over fifteen years for a murder that I did not commit,” Hastings wrote. “The most compelling of the evidence that has not as of yet been examined is the DNA evidence which will conclusively show that I was not the person involved with the deceased at the time of the crime.”

The prosecution informed Hastings that it was no longer in possession of the DNA evidence. Hastings continued seeking pro bono counsel to assist him in his efforts to prove his innocence. He ultimately enlisted the help of the Los Angeles Innocence Project at California State Los Angeles. Evidence was found and the court granted Hastings’s motion and ordered DNA testing be performed.

After George Gascon was elected District Attorney of Los Angeles County, he reaffirmed that office’s Conviction Integrity Unit (CIU). In June 2022, the DNA testing excluded Hastings and the CIU agreed the DNA profile should be submitted to the federal DNA database. The results identified that DNA profile as that of a convicted sex offender who had died in prison in 2020 while serving a 56-year sentence for an unrelated kidnapping and rape.

On October 20, 2022, with the agreement of the CIU, Hastings’s convictions were vacated, the charges were dismissed, and Hastings was released. He had spent more than 34 years in prison since the date of his conviction.

At a news conference a week later, Hastings declared, “I prayed for many years that this day would come. I thank the District Attorney’s Office, my attorneys and my family for standing behind me. I am just looking forward to moving forward. I am not pointing fingers; I am not standing up here a bitter man, but I just want to enjoy my life now while I have it.”

On March 1, 2023, Hastings was declared factually innocent following a motion filed by both the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office and the Los Angeles Innocence Project.

In April 2023, the California Victim Compensation Board awarded Hastings $1,945,720 in compensation.

In November 2023, Hastings filed a federal lawsuit against the Inglewood police department.

– Maurice Possley

|