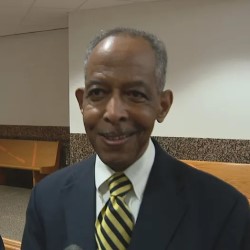

(Photo: Fox4news.com)

According to the initial police reports, the boys said that the assaults happened around 7:30 p.m. They said they were playing outside the building when a man approached and said he would pay them $5 to help him get into his apartment. They ended up entering through a window, and then kicking a hole through a wall.

Once they were inside the apartment, the man stole several items from the refrigerator as well as a television and a clock radio, making several trips from the apartment. The assailant threatened the boys with a pair of scissors, made them lie down, and then anally raped them. After the assailant left, the boys escaped and their relatives called the police.

In their first statements to police, the boys identified a suspect, a 14-year-old known in court records as J.M. (no relation), who lived near the grandmother. His nickname was Coco. B.M. also described the assailant as a Black man with blue dress pants, a striped shirt, tennis shoes and very short hair.” Officer R.M. McLeod of the Dallas Police Department wrote this report.

Police took the boys to Parkland Memorial Hospital for treatment and examination by Dr. Stephen Hardeman. In reports entered on June 12, Hardeman noted that both boys had bruising around the eyes, consistent with their reports of being hit in the face by the assailant. For each child, he wrote “14 y.o. assailant forced anal intercourse on pt.”

Both children underwent rape examinations. B.M.’s anal smear came back positive for the presence of sperm. No sperm was detected on L.M.’s smear.

On June 14, 1982, Officer Carole Gregston and Officer Paulette Dallman met B.M. at his home to talk about the investigation. They planned to drive to his grandmother’s house to take another look at the crime scene. Shortly after they left, B.M. told the officers that he saw the man who assaulted him. The officers circled the block for 45 minutes and called for backup, then took B.M. past the man for a second look. B.M. again said it was the assailant.

Police arrested 35-year-old Mallory Nicholson. Later that day, L.M. viewed a six-pack photo array including Nicholson. The boy did not make an identification, but his mother called the police and said L.M. had been scared. On June 15, 1982, the police conducted a live lineup for L.M. Again, the boy viewed six men, although Nicholson was the only one he had seen before. Each person in the lineup said, “Shut up boy or I’ll stab you with those scissors.” L.M. selected Nicholson as the assailant.

Nicholson was charged and later indicted for burglary and two counts of aggravated sexual assault.

Nicholson had an alibi. His wife, Barbara, had died of natural causes on June 8, 1982, and her funeral was on the afternoon of June 12, in Waxahachie, about 40 miles south of Dallas.

Numerous friends and family had seen him at the event and afterwards, as Nicholson packed up his belongings and made plans to move back to Baltimore, Maryland.

In a supplemental police report filed on June 17, 1982, Gregston said that the two boys told officers that their attacker had mentioned his wife’s funeral. That detail was not in McLeod’s earlier reports.

Attorney Lloyd Westerlage represented Nicholson. Prior to trial, Westerlage filed a motion in Dallas County District Court asking Judge R.T. Scales to order the state to disclose any exculpatory evidence and to turn over the entire case file to the court for inspection. Judge Scales granted the motion. But as a later review would note, “there is no indication in the record that the State or the Court turned over information to the defense.”

Separately, Westerlage filed a motion to inspect the testimony from the Grand Jury. Scales reviewed the testimony and then denied this motion.

At trial, the owner of the apartment testified that he returned home late on June 12, 1982, and found the police taking crime-scene photos. He testified that the assailant took a portable television, a tape deck, a radio, three pairs of pants, a clock radio, and some meat. These items were not recovered, and a police officer testified that it was unusual to not find any stolen objects at a suspect’s residence or nearby.

The two boys testified about being lured into the apartment and then being threatened with a pair of scissors and sexually assaulted. Each said that the man told them he was in a hurry because “he had to go to a funeral.”

Hardeman testified about his examination of B.M. and L.M. The state did not introduce his reports as evidence, and Westerlage did not question him about the contents of the reports.

Richard Dodge, a forensic technician for the police department, testified that he collected fingerprint evidence at the crime scene. Nicholson was excluded from prints found on the toilet tank. Dodge said he collected the scissors but did not test them for fingerprints. He also did not process the refrigerator door for fingerprints but testified that it was likely the perpetrator would have left his prints there.

While Westerlage built Nicholson’s defense around a case of mistaken identity, he did not introduce any evidence regarding J.M. Instead, he presented a parade of witnesses who said that Nicholson returned from Waxahachie at about 6:30 p.m., and spent the evening with his friends and family. Steven O’Neal testified that he accompanied Nicholson and some other men to Nicholson’s house at about 7:15 to pick up a television and a fan that Nicholson was giving away before he moved. After that, they went to O’Neal’s house and drank some wine.

Nicholson testified and said he did not assault the boys or break into the apartment. He testified in detail about his actions after the funeral, as he attended to his family and made preparations to move.

He also testified about his arrest. He said he had been sitting on the steps of a building with some other people when he saw two unmarked police cars cruising the neighborhood. The cars pulled over and a female officer got out and said she wanted to talk with him. He said he was not worried because he hadn’t done anything wrong. Another officer handcuffed Nicholson, and the police searched three duffel bags in his possession. They did not find anything linking him to the crime.

Nicholson said the officers didn’t tell him why he was under arrest, but he testified that he saw a boy in one of the unmarked cars whom he recognized as the friend of one of his sons.

During closing arguments, Westerlage told jurors that this was a case of mistaken identity. He said the testimony from the boys about their assailant having to go to a funeral had been “planted in their minds.” He made no mention of alternate suspects or the police investigation prior to B.M. identifying Nicholson.

In his closing argument, Prosecutor Mark Nancarrow said the boys’ testimony was critical and damning evidence. “What is the most telling factor those kids told you about?” Nancarrow asked. “The man that was with him said, ‘Hurry up because I have to go to my wife’s funeral.’ Now you know that there was a funeral on this man’s mind that day and you know he made that statement to those kids.”

The jury convicted Nicholson on September 24, 1982 of two counts of aggravated sexual assault and a count of burglary. He was sentenced to 55 years in prison.

Nicholson appealed. He argued that he had been convicted based on insufficient evidence and that the prosecutor had used inflammatory language. Most important, he said Judge Scales had erred in denying Westerlage access to the grand jury testimony.

The Court of Appeals for the Fifth Judicial District denied Nicholson’s claim on February 27, 1984. It said the evidence was sufficient. The court said that the testimony of Nicholson’s alibi witnesses still left a few gaps in his whereabouts on June 12, while also establishing that Nicholson was generally a few blocks away from the apartment building for most of the evening.

The court also said that Judge Scales was within his discretion in denying access to the grand jury testimony.

“There is only speculation in the instant case that the children testified before the grand jury and that their testimony there was different from their testimony at trial,” the court said. “It is apparent that appellant was seeking the grand jury transcript as a method of discovery. This is not permissible.”

Nicholson was released from prison on June 17, 2003. He moved to Maryland, and was required to register as a sex offender.

The Innocence Project began representing Nicholson, and, in 2019, the organization asked the Conviction Integrity Unit (CIU) of the Dallas County District Attorney’s Office to review the trial file in this case.

That review found substantial exculpatory evidence that had not been turned over to Westerlage, who had died in 1996.

■ McLeod prepared five separate reports naming J.M. or Coco as a suspect in the assaults and burglary. The first was at 12:35 a.m., on June 13, shortly after the boys reported the attack. The last was on June 17, after Nicholson was arrested. McLeod was not called to testify at trial, so Westerlage had no opportunity to question him about the investigation. Critically, none of these early reports mentioned anything about the assailant telling the boys that he had to go to a funeral.

■ The state also didn’t turn over Dr. Hardeman’s reports, which mentioned a 14-year-old suspect. (J.M. died in 1989.)

■ Notes in the prosecutor’s files referenced the name “Coco,” and said it was the defendant’s nickname. But that was the suspect, J.M.’s nickname, not Nicholson’s. These notes also gave a description of the suspect that was inconsistent with Nicholson’s appearance and hair length.

Most importantly, the state didn’t turn over transcripts of the grand jury testimony, which was at odds with the boys’ trial testimony. B.M. had testified at trial that the assailant said he had to go to a funeral. But testifying at the grand jury, he said that the man said, “He say a man broke in his house to kill – to kill – kill his wife. He said he gotta go tell a friend.”

Nicholson’s attorneys, Gary Udashen of Dallas and Adnan Sultan of the Innocence Project, filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus on February 22, 2021. In an accompanying memorandum, they said that Nicholson had maintained his innocence for nearly 40 years. “The State’s case rested solely on the two young victims’ identification of Mr. Nicholson,” the memorandum said. “The sole issue for the jury to resolve at trial was whether they could rely on those identifications beyond a reasonable doubt. In light of this, it is clear that had the jury heard favorable evidence contained in these reports which undermined the State’s case, there is a ‘reasonable probability’ that Mr. Nicholson would have been acquitted of this crime.”

In a response filed on March 4, 2021, the state conceded that it had failed to turn over evidence favorable to Nicholson’s defense and asked that his habeas petition be granted.

As part of the reinvestigation, the CIU obtained affidavits from Gregston and Nancarrow.

Gregston said she did not remember following up on any leads involving J.M. She said, “Eyewitness identification testimony was highly valued in the early 1980s and a positive eyewitness identification would have overridden an initial suspect mentioned in a patrol report, especially if two complainants identified the same person, as was the case with Mr. Nicholson.”

Nancarrow said he had no recollection whether the state turned over the documents to Westerlage but that at the time of the Nicholson trial, prosecutors had a much narrower view of what constituted exculpatory evidence and whether it needed to be disclosed. “The defense had to usually fight to view copies of any documents in advance and my position (as the State) was to oppose disclosing documents unless the defense could clearly articulate a legal reason for disclosure of the documents and I was ordered by the Court to do so.”

Nancarrow also said that eyewitness testimony affected the value of other evidence that might now be considered exculpatory.

The CIU’s response said that neither prosecutors nor Judge Scales disclosed the inconsistencies between B.M.’s trial testimony and his grand jury testimony, nor did they make any effort to correct his testimony.

There was also information in the state’s files indicating that the boys’ grandmother knew Nicholson’s wife and knew she had died. A note by the supervising prosecutor said “Parents know D somehow.” Nancarrow’s notes said, “Before this incident, [the boys’ grandmother] told [B.M.’s mother] that D’s wife had been killed and the funeral was the morning of 6/12/82.” This information was also not provided to Westerlage.

The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals granted Nicholson’s petition on November 10, 2021. Two judges dissented, writing that additional fact-finding was needed before granting relief.

On June 2, 2022, Judge Chika Anyiam granted a motion by the district attorney’s office to dismiss the indictments.

“I’ve said it before, there’s no time limit on seeking justice,” District Attorney John Creuzot said in a statement. “I am proud to say that today justice has, in fact, been done in the case of Mallory Nicholson – who is an innocent man.”

Prior to the hearing, Nicholson said, “I put it in God’s hand and I did it one day at a time hoping that this day would finally arrive. And it has, so I’m thankful to God.”

– Ken Otterbourg

|