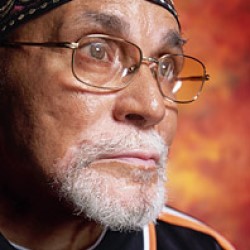

Khalil Islam in 2007, two years before his death (Photo: Andres Serrano/New York Magazine)

Nearly from the time that police arrested Aziz and Islam in the days after the murder, supporters of the men questioned their involvement in the crime. One observer later called the men’s case “an exoneration hiding in plain sight.”

The murder happened just after 3 p.m. on February 21, 1965. Malcolm was starting to give a speech at the Audubon Ballroom on 165th Street and Broadway in upper Manhattan, New York. At the time, Malcolm was a fiery, charismatic, and controversial activist, whose speeches about Black nationalism and confronting white racism were a stark departure from the exhortations for peaceful protest called for by many civil-rights leaders.

Suddenly, there was a disturbance in the audience, something about a pickpocket, and Malcolm called out, “Everybody be cool now. Don’t get excited.”

A man with a sawed-off shotgun rushed the stage and fired. Malcolm fell back. Then two other gunmen, one with a .45-caliber semi-automatic pistol and the other with a 9 mm Luger came forward and shot Malcolm.

Malcolm’s wife, Betty Shabazz, yelled out, “They’re killing my husband.” Malcolm was pronounced dead at Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center at 3:30 p.m. He was 39 years old.

The gunmen tried to flee, but a member of Malcolm’s security detail shot one of the assailants, and the crowd detained that man prior to his arrest by police. Talmadge Hayer, now known as Mujahid Abdul Halim, was 22 years old and lived in Paterson, New Jersey. He was charged with murder.

Police found several rounds of .45-caliber ammunition in his pocket. Ronald Timberlake recovered the semi-automatic pistol. He said he picked the gun up after Halim dropped it. Timberlake said he took the gun to his home in Brooklyn and disassembled it before turning the weapon over to the FBI.

Charles Blackwell said he recovered the shotgun and the Luger, but he would give differing accounts of what he did with the weapons. The police later found the shotgun in a room near the ballroom’s stage. The Luger was never recovered.

In the frantic days after the assassination, the FBI assisted the New York Police Department with the investigation and the hunt for the other participants. Law enforcement believed the killing was connected to Malcolm’s bitter split in 1964 with Elijah Muhammad’s Nation of Islam and his founding of the Organization of Afro-American Unity.

Based on witness interviews and other information, police arrested 26-year-old Muhammad Aziz, then known as Norman 3X Butler, on February 26, 1965, and 30-year-old Khalil Islam, then known as Thomas 15X Johnson, on March 3, 1965. Both men lived in the Bronx, New York. Police arrested them at their homes and later charged the men with murder in Malcolm’s death. Aziz and Islam knew each other from their work at the Nation of Islam mosque in Harlem, and they had been indicted on February 15, 1965, on assault charges tied to the January shooting of a man who had defected from Elijah Muhammad’s group.

Several witnesses who claimed to have seen Aziz and Islam would testify at their trial. However, there are no surviving records on the procedures or practices used by the police in the pre-trial witness identifications. In addition, no pre-trial hearings were held in an effort to suppress any of these identifications. The arrests took place two years before the U.S. Supreme Court would rule in U.S. v. Wade that defendants had a right to counsel during police lineups and that they could challenge the admissibility of these identifications prior to trial.

Aziz would tell investigators years later that he remembered standing in a room with a peephole. He said he was told he had been identified in a lineup, but he did not remember participating in one.

The combined trial of Aziz, Halim, and Islam began on January 20, 1966, in New York County Supreme Court, with Justice Charles Marks presiding. There was no physical or forensic evidence connecting Aziz or Islam to the murder. The state’s case against Halim was much stronger.

Along with the .45-caliber ammunition police found in Halim’s pocket, a police witness testified that bullets removed from Malcolm’s body were consistent with the gun Timberlake gave to the FBI. In addition, a police witness testified that Halim was the source of a thumbprint found on a strip of film on a smoke bomb recovered from the ballroom.

The state presented 10 witnesses who said they saw Halim at the ballroom. Of those 10, six also said they saw Aziz; four said they saw Islam. Their accounts varied, particularly in their testimony about how the events unfolded during the chaotic scene during and after the shooting as hundreds of people scrambled for safety.

Cary Thomas testified that he arrived early at the Audubon and saw Islam, whom he recognized from a Nation of Islam mosque in Manhattan, sitting in a booth facing the stage. Thomas said that after he heard the shotgun blast, he looked at the stage and saw Islam holding a sawed-off shotgun. He said he then saw Halim and Aziz race forward, guns in hand, and begin shooting.

Defense attorneys tried to exclude or limit Thomas’s testimony, questioning whether he was mentally competent to testify. Justice Marks had asked the state whether Thomas had been declared “psychotic” or “anything else,” and the state said it had no knowledge of any issues. On cross-examination, Thomas denied ever receiving psychiatric treatment. The defense then introduced records of Thomas’s hospitalization. Marks first barred the admission of these records but later allowed the defense to present the records after Thomas left the witness stand.

Vernal Temple also testified that he saw Islam at the Audubon that afternoon. He said he recognized Islam because he had previously seen him at a mosque in Chicago.

Fred Williams testified that he heard the shotgun blast and pushed his wife to the floor to protect her. He looked up, heard another blast and pistol shots, and saw Islam facing the audience and holding a sawed-off shotgun.

According to the state’s witnesses, Aziz was one of the men who had staged the pickpocketing distraction. Jasper Davis testified that he was sitting near the front of the Audubon when a man he later identified as Aziz sat down next to him. They spoke for a few minutes. Then another man sat down next to Aziz. Just before Malcolm began to talk, one of the two men jumped up and said, “Take your hand out of my pocket.” Other witnesses, including Thomas and Blackwell, said Halim was Aziz’s partner in the distraction. Blackwell also said he saw the two men run to the stage and shoot Malcolm.

The witnesses differed on where Aziz and the other man sat in the ballroom. Edward DePina said the men were in the front row. Davis said they were near the front of the ballroom. Thomas and Williams said they were at least 12 rows back.

Several witnesses said they saw Aziz and Islam in the moments after the shooting, as they tried to flee the scene. Blackwell said he saw Islam running into the ladies’ lounge. Timberlake said he knocked Aziz down with a “body block” and later could see Aziz being “pummeled by the crowd.”

Attorneys for Aziz and Islam tried to show other discrepancies in the testimony of the state’s witnesses. Blackwell, for example, gave different accounts at trial and before the grand jury about who he gave the weapons to. Thomas had told the grand jury that he saw Islam with a pistol. At trial, he testified it was a shotgun.

Aziz and Islam each testified in their own defense. Aziz said that on February 21, 1965, he had injuries to his right leg that left him with a limp and prevented him from running. That morning, he went to the emergency room of Jacobi Hospital, where he was treated by Dr. Kenneth Seslowe. He came home around 1 p.m., and rested his legs, per the doctor’s advice. Aziz said he heard about the shooting from the radio and called the mosque, eventually speaking with a man he referred to as “Captain Joseph.” Seslowe also testified and confirmed Aziz’s visit to the emergency room.

Islam testified that he was at home all day on February 21 and did not leave until the evening. He said he did not see Aziz at any point that day. Both men also had their spouses and friends testify that they were at home at the time Malcom was murdered.

In addition, Aziz presented testimony from a man named Ernest Greene, who said he saw the shooting and that the man with the shotgun was “stout and very dark and had a very deep beard.” This did not fit the description of Islam, who was of average build, light-skinned, and clean-shaven at the time of his arrest.

Halim took the stand on February 23, 1966, testifying in his own defense. He said he was not a Black Muslim or a member of any organization affiliated with Elijah Muhammad. He said he didn’t belong to a mosque. He said he didn’t know Aziz or Islam and had no role in Malcolm’s death. He admitted that he was at the Audubon Ballroom on February 21, but he said he found the ammunition in the ballroom’s bathroom and put it in his pocket.

Three days later, Halim returned to the stand, called by Aziz’s attorney, William Chance. Now, he confessed to taking part in Malcolm’s murder but said that Aziz and Islam were not involved. He said he had never met them until they became co-defendants. “I just want to testify that [Aziz] and [Islam] had nothing to do with it,” he said. “I was there. I know what happened and I know the people who were there.”

Halim admitted that he shot Malcolm with a .45-caliber pistol, but he said that he wasn’t one of the men who created the distraction. He said that he and another man sat in the front row with pistols. A third man sat a few rows back with the shotgun, and a fourth man started the “commotion” by pretending his pocket was being picked. He described the shotgun shooter as “husky” with “dark skin” and a beard. He refused to name the other participants, but he said none was a member of the Black Muslims.

Halim said he had decided to “tell the truth” after a brief conversation with Aziz and Islam earlier that day. During his cross-examination of Halim, Assistant District Attorney Vincent Dermot said Halim had lied under oath in his previous testimony and now was violating his oath to tell the whole truth. “Isn’t the reason, that if you told the whole truth, you’d have to say it was [Islam] who held the shotgun and [Aziz] who fired the pistol?”

“No sir,” said Halim. “It’s not true.”

The jury convicted all three men of murder on March 11, 1966. A month later, they were sentenced to life in prison.

Aziz and Islam quickly appealed, but the First Department of the Supreme Court’s Appellate Division affirmed the convictions on April 18, 1968. The New York Court of Appeals affirmed that decision a year later.

Nine years later, Aziz and Islam moved to vacate their convictions, primarily on the basis of newly discovered evidence, including redacted FBI records. Ten affidavits were submitted in support of the motions.

Halim’s affidavits identified his co-conspirators. He said the members of the group included him, Leon Davis, Benjamin Thomas, a man he knew as “Wilbur or Kinly,” and William X. He said they were all Nation of Islam members from New Jersey. Halim described how he was recruited to participate and the roles that each man played in the murder. Halim said he and Davis were in the front, with William behind them, and “Wilbur” in the back of the ballroom.

The motion to vacate also included an affidavit from Benjamin Karim, Malcolm’s assistant minister, who spoke to the Audubon audience just before Malcolm. Karim said he had time to scan the crowd and saw neither Aziz nor Islam. Both men, Karim said, were known to Malcolm’s security team and would have drawn scrutiny if they were present.

The motion also said that an undercover police officer named Eugene Roberts had been in the ballroom and witnessed the murder. Roberts’s presence had become known in an unrelated 1970 criminal trial. In that case, he testified, he was posing as a member of Malcolm’s security team. He said that “two individuals near the front of the auditorium jumped up” to create a distraction. Shots were fired as Roberts went to confront them. Roberts said Halim shot at him but missed, and that he then hit Halim with a chair.

The motion argued that Roberts’s testimony differed from the state’s witnesses. None said Halim had been hit with a chair, and Roberts’s testimony about the location of the two men who caused the distraction conflicted with some of the witness accounts.

The state’s response included an affidavit from Roberts that said he had no reason to believe Aziz and Islam were innocent and that the New York Police Department was not involved in Malcolm’s death.

The state also noted that Karim’s affidavit was at odds with his grand jury testimony, where he said he didn’t know whether Islam or Aziz were in the audience.

As part of its response, the state obtained the non-redacted versions of the FBI records and submitted them to the court for review. It said the records did not support the claims of Aziz and Islam. It also said that the FBI had declined to provide prosecutors with additional non-redacted records, telling the New York District Attorney’s Office that the records were not readily available and that “there appears to be nothing in any of these redacted documents which corroborates the allegations in [Halim’s] affidavits, or which is otherwise supportive of the instant motion.”

Justice Harold Rothwax of the New York County Supreme Court denied the motion to vacate on November 1, 1978. He wrote that he “must question the reliability of any identification which comes thirteen years after the events in question to inculpate persons who apparently were never the object of suspicion despite the thorough efforts of local, state and federal law enforcement officials.”

On December 31, 1979, Aziz and Islam filed a petition for writs of habeas corpus in U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. The petition included additional information from Halim about his alleged co-conspirators, including that William X’s last name was Bradley, and that he was a known “stick-up man.” Judge Thomas Griesa dismissed the petition exactly one year later.

Aziz was released from prison on June 24, 1985. Islam was released on February 10, 1987. He died in 2009. Halim was released from prison in 2010, although he had been on work release for the previous 22 years, working as a counselor.

Aziz and Islam stopped their appeals after 1980, but public interest in the case never waned. Lawyers, politicians, journalists, and historians continued to ask questions about whether Aziz and Islam were wrongfully convicted, and, if so, who collaborated with Halim in Malcolm’s murder.

In 2010, a historian named Abdur-Rahman Muhammad published on his blog that a William Bradley from Newark, New Jersey, was the man with the sawed-off shotgun. Bradley had changed his name to Al-Mustafa Shabazz. Muhammad’s blog did not give the source of this information. Muhammad’s reporting later found its way into Manning Marable’s Pulitzer prize-winning biography of Malcolm in 2011, and Muhammad was a central character in a Netflix documentary, Who Killed Malcom X that began streaming on February 7, 2020.

At the time of the Netflix release, New York District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr. opened a reinvestigation into the convictions. His office’s Conviction Integrity Unit (CIU) worked with the Innocence Project and with the office of civil-rights attorney David Shanies to conduct a wide-reaching examination of Aziz’s and Islam’s convictions.

The records included trial transcripts and court documents, as well as documents from the FBI and the police department’s Bureau of Special Services and Investigations that had not been shared with the district attorney’s office or the defendants’ attorneys.

The district attorney’s office would later note the significant challenges in the search for truth. “The murder of Malcolm X occurred more than 56 years ago,” it wrote. “Many of the persons whom we wanted to interview are deceased. All of the main police investigators and the lead trial prosecutor are deceased. The defense attorneys at trial and during the 1970s post-conviction proceedings are deceased. Every eyewitness who testified at trial is deceased. All of the eyewitnesses who identified the defendants but did not testify at trial are deceased. Many of the other suspects who were not arrested are deceased or could not be located.”

Nearly two years later, on November 18, 2021, Vance’s office moved to vacate the convictions and dismiss the charges against Aziz and Islam. The motion said that it could not make a determination on their actual innocence, but that the men were denied a fair trial because their attorneys were denied access to exculpatory evidence that could have tipped the verdict toward acquittal.

Much of this new evidence had been in the possession of the FBI. It included:

■ An FBI report from February 22, 1965 that said “the killers of Malcolm X were possibly imported to NYC,” and that the shooters were “two men, occupying the front seats, left side of middle aisle.” The report gave a description of the man with the shotgun as “a negro male, age twenty-eight, six feet two inches, two hundred pounds, heavy build, dark complexion, wearing gray coat.” The description was similar to that provided by Greene. It also did not describe Islam.

■ FBI reports detailing that one of the men who testified against Aziz was an FBI informant, and that the FBI was not to tell the police department about this relationship. This order came from FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover.

■ An FBI report suggesting a motive for the murder, which had to do with Malcolm accusing another man of stealing money from his organization.

■ Reports that several witnesses failed to identify Islam as one of the shooters.

■ A file dated September 28, 1965, on William X Bradley, containing information compiled between 1963 and 1965. Bradley, who was described as dark-skinned and stocky, was listed as a Nation of Islam “strongman” who had engaged in acts of violence. The file also noted he had served as a machine gunner in the Marine Corps.

Previously undisclosed police files provided other leads. They included two tips that the assassination was the work of the Revolutionary Action Movement, as well as a report on the activities of the undercover officers at the Audubon Ballroom.

The motion to vacate noted that prosecutors were aware that three undercover detectives were present at the ballroom that afternoon. A note in the prosecutor’s trial file indicated that one of the officers had identified Aziz as being involved in the shooting, but it didn’t say the basis for this identification.

Prosecutors also had a police report detailing an interview on March 22, 1965, with Augurs Linwood X Cathcart. He said he was near the front when the shooting started. He also said he knew Islam and Aziz well and did not see them at the ballroom. The CIU report noted that it was unclear whether this report was turned over to the defense, but regardless, it contradicted a statement made in court by a prosecutor in the 1970s that “The District Attorney’s Office case file contains nothing which supports any of the defendant’s allegations or contentions.”

During the 22-month review, attorneys with the district attorney’s office and those representing the defendants interviewed a man known as J.M. He said he had answered the phone at the Harlem mosque when Aziz called just after 3 p.m. on February 21, 1965. He said he found a supervisor, Joseph X, who then called Aziz back. J.M.’s daughter told the investigators that her father had repeated this account through the years.

Halim declined to be interviewed.

Aziz told investigators that he remembered calling the mosque and talking with Joseph X about the shooting. He said Joseph told him to go to a neighbor’s apartment and ask for a cup of milk and eggs. Aziz said Joseph didn’t give an explanation for the request, but Aziz assumed it was to make sure someone else knew he was in the Bronx at the time of the shooting. Aziz didn’t follow through with Joseph’s request; he said he didn’t know his neighbors.

Roberts, the undercover officer, was also dead, but investigators found that in interviews given after his 1978 affidavit, he had said the shooters were in the front row at the ballroom. This lined up with Halim’s testimony about where the shooters sat.

The motion to vacate said that while several of the eyewitnesses knew either Aziz or Islam, which made their identifications potentially stronger, the state’s case contained several critical weaknesses. First, both Aziz and Islam had alibis supported by friends and family. Second, the state offered no evidence that Aziz and Islam knew Halim, who was from New Jersey, and affiliated with the mosque in Paterson. Aziz and Islam were members of the Harlem mosque.

Although the motion to vacate said that attorneys for Aziz and Islam didn’t receive this exculpatory evidence, it was less certain what evidence they were entitled to at the time of the trial. The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Brady v. Maryland, requiring prosecutors to turn over exculpatory evidence, was handed down in 1963, but the initial ruling only applied to material in the prosecutor’s files. It would be more than 30 years before the Supreme Court, in Kyles v. Whitley, extended Brady protections under the principle of constructive knowledge to include exculpatory evidence that remains with the police and other law-enforcement agencies.

The motion noted that state prosecutors don’t typically have constructive knowledge of the FBI’s information, unless there is a joint state-federal investigation. The investigation into Malcolm X’s assassination wasn’t fully “joint,” the motion said, but there was enough cooperation and sharing of information to view it through that lens when determining the importance of the FBI’s documents. The motion said that appellate courts have not decided on whether the so-called Kyles protections are retroactive.

“Nevertheless,” the motion said, “given the unique facts of this case, and based on fundamental fairness and the interests of justice, we submit that, without the exculpatory material that was in law enforcement’s possession, these defendants did not receive a fair trial, and we respectfully submit that their convictions should be vacated and the indictment against them be dismissed.”

The motion said the reinvestigation did not uncover any evidence to support the assertion that Malcolm’s murder had been “orchestrated” by the FBI or the New York Police Department.

Justice Ellen Biben of New York Supreme Court vacated the convictions and dismissed the charges against Aziz and Islam on November 18, 2021. She said to a packed courtroom, “I regret that this court cannot fully undo the serious miscarriages of injustice in this case and give you back the many years that you lost.”

Prior to Justice Biben’s ruling, Vance said, “I want to begin by saying directly to Mr. Aziz and his family, and the family of Mr. Islam, and of Malcolm X that I apologize. We can’t restore what was taken from these men and their families, but by correcting the record, perhaps we can begin to restore that faith.”

Aziz said the ruling was welcome but insufficient. The harm to his life had been done. “I do not need this court, these prosecutors or a piece of paper to tell me I am innocent. I am an 83-year-old who was victimized by the criminal justice system.” He said his wrongful conviction fit a pattern, one “that is all too familiar to Black people.”

Shahid Johnson, one of Islam's sons, said, “Right now, this is great, but not so great at the same time. I am happy, but there's still sadness. That's how I feel.” He continued: “The fact that the family suffered, growing up with concerns of fear, of people coming after us ... those kind of things you can't get back," Johnson went on. "Normality was gone when I was 10.”

Vanessa Potkin, the director of special litigation at the Innocence Project said in a statement: “It took five decades of unprecedented work by scholars and activists and the creation of a Conviction Integrity Program at the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office willing to engage in a true joint re-investigation for these wrongful convictions to be officially acknowledged and rectified. The recently unearthed evidence of Mr. Aziz and Mr. Islam’s innocence that had been hidden by the NYPD and FBI not only invalidates their convictions – it also highlights the many unanswered questions about the government’s complicity in the assassination – a separate and important issue that, itself, demands further inquiry.”

On November 17, 2021, a reporter for the New York Times knocked on Halim’s apartment door in Brooklyn. He was told of the impending motion to vacate his co-defendants’ convictions. Through a closed door, Halim said, “God bless you. They’re exonerated.”

Aziz and Islam's estate filed claims against New York State for at least $20 million in compensation in December 2021. In July 2022, they filed a federal civil-rights claim against the City of New York, seeking $40 million in compensation. The state compensation claims were settled in April 2022, with Aziz and Islam's estate each receiving $5 million. The civil-rights lawsuit was settled in October 2022, with Aziz and Islam's estate splitting an award of $26 million. In November 2023, Aziz and the estate of Islam filed a $40 million lawsuit against the FBI.

– Ken Otterbourg

|