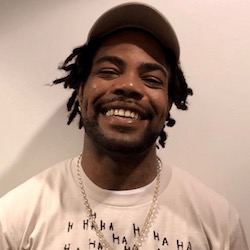

James Davis (Photo courtesy Legal Aid Society)

The police focused on 21-year-old James Davis after Tina Black Jr., who wasn’t at the party, told police that he was the gunman.

Two weeks after Tina Black’s tip, detectives asked Harper’s brother-in-law, Jose Machicote, who had been at the party with Harper when Harper was killed, to come to the police station to view a photographic lineup. When he came to the station, Machicote said the gunman was a brown-skinned man with braids. The photographic lineup included a picture of Davis when he was younger and had his hair in braids. Machicote selected Davis as the gunman.

On March 25, 2004, police arrested Davis. He had short hair, not braids. He told police he attended the party to celebrate his younger brother’s birthday, but had too much to drink, began vomiting and left in a taxi to meet his then-girlfriend before any shooting occurred.

After Davis was arrested, Harper’s mother reached out to two of her dead son’s friends, Harold Pou and Shawn Belton, and asked them to go to the police station. She told them the police “think they have somebody that fit the description” and the police wanted somebody “to verify” that that person was the gunman.

Pou said he viewed the array and told police that Davis looked “similar” to the gunman. Belton had given no prior description of the gunman, but now claimed that just before he viewed the lineup, he told police that he had given a description. He said the gunman was a light-skinned Black man about 5 feet 10 inches tall and wearing a black skull cap. Belton identified Davis as the gunman. Davis likely stood out in the photo array. He had a medium complexion and was 5 feet 7 inches tall, while the fillers included a heavy-set dark-skinned man, a short dark-skinned man, and two other heavy-set men, one of who was tall and appeared to be West Indian.

On November 10, 2005, Davis went to trial in Kings County Supreme Court on charges of second-degree murder and criminal possession of a weapon. Machicote identified Davis as the gunman.

Pou testified that he and Harper had been friends for 15 years. He told the jury that Machicote got into an argument with someone near the end of the party. Harper, Pou, and some others joined in and people were arguing and pushing. Pou said he heard shots and saw, in profile, a light-skinned man with braids. When the prosecutor pressed him, Pou said, “The guy over there [Davis, sitting at the defense table] resemble [sic] him, but I know the guy had braids. Like that’s [t]he main thing that I really knew about it. He [the shooter] was light-skinned with braids but he [Davis] resemble him.”

Belton testified that Machicote got into an altercation with someone, and Harper went over to help him. Belton also described the gunman as having braids. He identified Davis as the gunman.

Davis’s defense lawyer, Joel Medows, called as his only witness Kaneen Johnson, who was Davis’s girlfriend at the time of the shooting. She testified that she and Davis argued that night because she did not want Davis to go to the party. Davis insisted on going because his younger brother, Daniel, was celebrating his 17th birthday at the party.

Davis called her about 2:30 a.m. to say he was taking a taxi from the party and would meet her outside the home where she lived with her mother. When the cab pulled up, Davis got out and promptly vomited on the street. She said he was staggering and slurring his words. They walked to her aunt’s house and spent the night there because Johnson’s mother and Davis did not get along.

Johnson testified that Davis had a low Caesar cut, not braids or cornrows. She said he had longer hair until 2003, when he had his head shaved because of a skin condition and he had kept it short ever since.

At the time he was first interviewed by police, Davis gave the police the names of several people who he said were at the party and could corroborate his account. However, neither the police, the prosecution nor Davis’s defense attorney ever spoke to any of them. None of them was called to testify.

On November 23, 2005, a mistrial was declared when the jury was unable to reach a unanimous verdict. The jury reported that it was deadlocked with 11 jurors voting to acquit and one juror voting to convict.

In May 2006, Davis went to trial a second time. Machicote again identified Davis as the gunman. He said that Harper got into an altercation and that when he tried to intervene, shots were fired. Machicote had an extensive record of arrests and convictions, but he maintained that he worked as a barber and had given up his life of crime.

Pou was not available to testify, so the prosecution was allowed to read his testimony from the first trial saying only that Davis resembled the gunman.

Belton testified only after he was arrested on a material witness warrant and brought to court. He recanted his identification of Davis. Belton said that he saw Harper move toward the altercation and then saw sparks from the gun as it was fired. He said he only “glanced” at the gunman and could not identify him.

Medows called no witnesses for the defense at this trial.

On May 15, Davis was convicted of second-degree murder and criminal possession of a weapon. He was sentenced to 18 years to life in prison.

Davis’s appellate attorney, Susan Epstein from the Legal Aid Society, interviewed the six witnesses whose names Davis had provided to police and to Medows, but who had not been called to testify. All six said that Davis left the party early—drunk and sick. Epstein asked the Brooklyn District Attorney’s Conviction Review Unit (CRU) to reinvestigate the case. The CRU spoke to each of the defense witnesses, and to Davis himself, but declined to recommend the convictions be vacated. Epstein then moved to vacate the judgment in the original trial court.

At a hearing on the motion, eight witnesses, including Davis, testified that he was not at the hall when the shooting occurred.

Ernest Hollman, one of the party’s promoters, testified that he joked with Davis about his hairstyle when Davis arrived at the party. Hollman said James wore his hair short in a Caesar style with waves.

Jamel Black testified that he tried to avoid Davis that night because he was angry with him for sleeping with Black’s girlfriend. He said he was in the bathroom with Daniel Davis and others, smoking marijuana, when Davis came in. He left when Davis came in. He said he then saw Tay Hall, whom he knew because they had once sold drugs on the same street corner in Brooklyn. He and Hall were smoking marijuana when Jamel’s brother, Nathaniel, told him that Davis wanted to see him in the bathroom. Jamel said he heard people laughing when he entered and he was suspicious they were laughing at him, but he then saw that they were laughing because Davis was throwing up in a bathroom stall.

Jamel said Davis came out of the stall and attempted to give him a high five, but Black put up his fist instead and walked out. Not long after, Davis got into the taxi and left.

When the last call for drinks was made, Jamel and his brother, Nathaniel, agreed to split a bottle of champagne. His brother went to buy the bottle and Jamel went to hang out with a girl. When his brother did not come back, Jamel went looking for him. He said he found him at the front of the dance floor arguing with a Puerto Rican man in a fur coat. Nathaniel told Jamel the man had snatched the bottle of champagne from him because Nathaniel had stepped on his foot. Jamel tried to grab the bottle from the man, but the man pushed him away. At that point, a Black man who was with the Puerto Rican man told Jamel to “break out” because this had nothing to do with him, and pushed Black into someone behind him, who in turn said, “There ain’t gonna be no shit in the club, this shit is about to be over, we gonna replace the bottle.” At that point, Jamel returned to where the girl was waiting for him while his brother went to get another bottle.

Jamel said he decided to leave. While waiting at the coat check, he heard someone say, “You thought this was over,” and then felt a pain in his back. Jamel said he turned around and saw the Black man who had pushed him earlier, weaving his way through the crowd headed toward the exit door. Jamel said he tried to follow him, but felt immense pain, and instead decided to find his brother.

As Jamel was walking toward the back of the club, he ran into Hall, who offered to take him to the hospital. As they headed for the door, Jamel said he heard Hall say, “Oh, shit,” and then Hall pushed him to the floor. Jamel said he heard at least three gunshots and then saw Hall putting a small, silver revolver in his pocket. Hall said he had to leave before the police came and ran toward the door.

Jamel then saw the Black man he had argued with earlier. The man was bloodied and lying on the floor with a knife next to him.

Jamel said that Daniel Davis and another man helped get him to his grandmother’s building. An ambulance was called and Jamel passed out. When he awoke, he was in the hospital with 26 staples in his body.

Jamel underwent two surgeries at the hospital. After the first one, police questioned him. Jamel said he thought the police were accusing him of being the gunman. He said he told them about being stabbed and seeing Hall, whom he identified only as “Tay,” putting the gun into his pocket. Jamel refused to give Tay’s last name.

After he was released from the hospital, Jamel saw Hall again. Hall said that Black “owed him one.”

Corey Hinds testified that James Davis was not there when the fight broke out. He heard Jamel yell, “I got stabbed.” Hinds said he was going to the bar for last call when he heard gunshots. He did not see the gunman.

Keenan Johnson testified pursuant to a material witness order. She repeated her testimony from the first trial about spending the night with Davis after he showed up sick and drunk around 1:30 a.m.—about two and a half hours prior to the shooting. They walked to the apartment of Johnson’s aunt, Wanda Chapman, where they spent the rest of the night. Johnson said Davis threw up once more at the apartment. While watching the news the next morning, they heard about the fatal shooting at the Masonic Temple.

Chapman testified that she let Davis and Johnson into her apartment sometime prior to 2 a.m. She heard someone vomit but did not know who it was. Chapman said Johnson and Davis remained there for the rest of the night.

Davis testified that he gave the names of his alibi witnesses to police when he was questioned and that he also gave them to Medows. Davis said that Medows told him that the other witnesses were not needed. Davis said that Medows told him that Johnson did not come to the second trial because she blamed the defense for getting kicked out of her mother’s house. The prosecution had issued a subpoena, and police served it at Johnson’s mother’s house at midnight. When Johnson’s mother learned Johnson had been subpoenaed to testify at a murder trial, she kicked Johnson out of the house. Johnson blamed Davis and refused to come to court.

Asia Snow testified that she had regularly braided Davis’s hair until 2002 when his hair became so brittle it would break off when she tried to braid it.

Davis and Johnson both testified that he cut his hair short in 2003 because he had ringworm, a fungal infection of his scalp.

Tina Black’s mother testified that her daughter, who was known as “TT,” was in love with Davis and when he did not return her feelings of affection, she became angry. At that time, TT was sick—on dialysis—and refused to take care of herself. She did not attend parties because of her condition. She needed a kidney transplant, suffered from diabetes, and had congestive heart failure. Before TT died in 2013, she admitted she had falsely accused Davis because she was jealous that he was dating another woman.

Tina’s mother testified that when she asked her daughter why she did “something stupid like that,” Tina replied that Davis had “kicked her to the curb like an old boot.”

The defense also sought to introduce an affidavit from Davis’s brother, Daniel, who had since been killed. In the statement, Daniel said he had found Davis at the party asleep in a chair, holding a bottle, and put him into a taxi. Daniel said that he returned to the party and was still there when the shooting occurred. He said he encountered Jamel Black, who had been stabbed. Daniel said he brought Jamel to Daniel’s apartment and that Jamel later went to the hospital for treatment. The court declined to allow the statement into evidence.

The defense also sought to call two expert witnesses, but the court refused to allow them to testify. Nancy Franklin, a psychologist, would have testified that there were factors that made the identifications unreliable, including the circumstances of the shooting. Gregory Donaldson, a professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and author of “The Ville: Cops and Kids in Urban America,” would have testified about the deep-seated distrust between young Black men and law enforcement that was prevalent in Brooklyn in the early 2000s. Donaldson’s testimony would have explained why the defense witnesses would have been reluctant to go to the police on their own initiative at the time of Davis’s trials. The court declined to hear from either of the experts.

After the evidentiary hearing concluded, the defense requested to reopen it to present evidence relating to Machicote, who had been murdered In November 2006, six months after Davis was convicted. The FBI revealed that Machicote had been the subject of a drug trafficking investigation and was considered a violent criminal. He was killed when he tried to rob a rival drug dealer for the second time. The drug dealer responsible for Machicote’s murder had been convicted in federal court.

The defense contended that the evidence showed that Machicote had lied at Davis’s trial when he portrayed himself as a neighborhood barber who had put his criminal ways behind him. The defense sought to subpoena the FBI agent in charge of the investigation of Machicote to determine whether New York police or the prosecution knew of Machicote’s activities at the time of Davis’s trial.

Initially, the court agreed to sign the subpoena and reopen the hearing, but subsequently reversed the ruling and denied the motion to reopen.

In January 2020, Justice Danny Chun denied the motion for a new trial, concluding that the defense “failed to demonstrate by clear and convincing evidence that he is actually innocent.” The court said that the evidence that Davis left the party before the shooting was not credible. He said that none of the witnesses could definitively state “that the defendant was not the shooter, or even that the defendant was not present at the club at the time of the shooting.” And he refused to credit Davis’s testimony, calling him “absolutely the most interested witness and given such an overwhelming amount of self-interest” his testimony was not credible and not reliable.

The defense appealed. On April 21, 2021, the Appellate Division, Second Department, reversed the lower court’s ruling and vacated Davis’s convictions.

The appeals court ruled that Medows, Davis’s defense attorney, had provided an inadequate legal defense. “Here, the failure by the defendant’s trial counsel to contact and interview these witnesses cannot be characterized as a legitimate strategic decision since, without collecting that information, counsel could not make an informed decision as to whether the witnesses’ evidence might be helpful at trial.”

By then, another of Medows’s clients, Joel Fowler, had been exonerated of a murder he did not commit. Fowler was convicted in 2009 of a 2007 murder and sentenced to 25 years to life. In part, Fowler’s convictions were overturned because Medows failed to call witnesses who would have testified Fowler was not the gunman.

On May 10, 2021, Davis was released pending a retrial.

On August 3, 2021, the prosecution dismissed the case, stating that witnesses were not available to testify for the prosecution.

“James Davis never committed this crime, and despite overwhelming evidence of innocence, he spent the past 17 years—his entire adult life—behind bars,” said Elizabeth Felber, Director of the Wrongful Conviction Unit at The Legal Aid Society. “While today provides some justice for James, it does not recoup the almost two decades of his life that were taken from him.”

Felber said the eyewitness identifications “were always troubling” and that “tunnel vision by law enforcement” resulted in a failure to investigate Davis’s alibi evidence.

“Sadly—as is often the case—his defense counsel failed James Davis as well,” Felber said. “Never investigating any of the witnesses at the party who could have told him, not just that James had left well before the shooting took place, but who actually committed this crime—a man named Tay Hall.”

In November 2022, Davis filed a federal civil rights lawsuit seeking compensation for his wrongful conviction.

– Maurice Possley

|