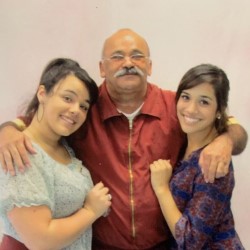

Antonio Martinez, with his granddaughters, Shayla Rivera, left, and Talia Santiago, right. (Photo/Philadelphia Inquirer)

Detectives with the Philadelphia Police Department investigated and quickly developed a theory that the Camachos had been killed over a drug deal gone bad. A man named Wilson Santiago emerged as a leading suspect. He owned a small candy store near the location of the shootings that police believed was a front for a drug operation. Juana Camacho told police that she had heard that Santiago shot her sons over a dispute. An anonymous caller told police that Santiago was the shooter. Other witnesses also seemed to point to Santiago.

During the summer of 1985, the District Attorney’s Office prepared to present a case to a grand jury. A prosecutor was assigned the case on October 23, 1985. The plan was to bring in Santiago and his wife for police questioning and to tell them that they might be subpoenaed before a grand jury. But the Santiagos could not be found. There is no record that any witnesses were called before the grand jury, and the proceedings were sealed.

In 1986, two other witnesses, Radame Lopez and Maria Torres, told police that Santiago was responsible for the murders. Lopez said Santiago and Santiago’s cousin, whom he said was named “Tony,” shot the Camachos. He described Tony as tall, thin and clean-shaven.

Separately, Torres said she had seen the shootings and watched Santiago drag Hector Camacho’s body from the store. The police did not get a written statement from Torres. They made plans to follow up with her, but that meeting never occurred.

The investigation dried up. Three years later, police got a tip from a man named Angel Fuentes, who had a lengthy criminal record and was looking for some assistance on getting reinstated into a work-release program. Fuentes said that he had seen the Camacho brothers arguing with a man named “Tony,” who had a pistol. Fuentes said he heard the shots and saw the brothers fall to the ground. Fuentes said he had known Tony for about a year and that Santiago called him “compadre.”

Separately, Santiago’s stepson, Jose DeJesus, told police on March 22, 1989 that a man named “Tony,” who was his stepfather’s brother-in-law, had killed the Camacho brothers over an unpaid debt.

The Tony named by DeJesus was Antonio Martinez, who also went by the name Pedro Alicea and was 37 years old at the time of the shooting. And unlike the Tony described by Lopez, Martinez was short, overweight, and had a mustache. After his initial contact with the police, Fuentes would pick Martinez out of a photo lineup as the man he saw shoot the Camachos.

Police arrested Martinez on March 24, 1989 and charged him with murder in the deaths of Hector and Luis Camacho.

Martinez was from Puerto Rico and at the time did not speak English. His trial in the Philadelphia County Court of Common Pleas began in the spring of 1990. He waived his right to a jury trial and had his case heard before Judge Theodore McKee. Prior to the trial, his attorney, John Scott, asked the district attorney’s office for the files from the police investigation and was given witness statements from Fuentes, Santiago’s stepson, and another man.

Fuentes testified that he saw the shooting and that both victims were unarmed. He said that he not come forward initially but went to the police after he was arrested on unrelated charges, thinking “perhaps they will help me.” Over the years, Fuentes had provided information to Detective Miguel Deyne, and Fuentes approached Deyne to tell him about the shooting. Fuentes testified that he was promised nothing in return for his testimony. A police officer testified that he had told Fuentes he would speak to the judge in Fuentes’s case but that was the limit of their arrangement.

During his cross-examination, Scott wanted to question Fuentes about a case involving Fuentes’s son, who had been charged with murder. But McKee sustained the state’s objection that this was irrelevant.

Just prior to the trial, the state had found another witness, Renaldo Velez. He testified that Martinez had shot the Camacho brothers in self-defense after they approached Martinez holding their own weapons.

Before closing arguments, McKee cautioned both sides about how to present their case. “Let me mention, to the extent I can limit it, don’t spend too much time hammering on Mr. Fuentes’ testimony…There are a lot of problems with his testimony.”

Still, McKee convicted Martinez on May 2, 1990, of first-degree murder in the death of Hector Camacho, voluntary manslaughter in the death of Luis Camacho, and two counts of possessing an instrument of a crime. He sentenced Martinez to life in prison.

Martinez’s first appeal focused on judicial error and whether Scott had been ineffective in establishing the benefits that Fuentes received for testifying. Prior to the trial, Scott had reached out to Fuentes’s attorney, Richard Shore, who said he would testify about his client’s arrangements with police and prosecutors. But Scott never called Shore to testify. Fuentes had been reinstated into work release prior to testifying at the preliminary hearing, then paroled from that program after the hearing. After the trial, Fuentes was given probation on a drug conviction that normally would have required incarceration.

“There is no doubt in my mind that Angel Fuentes was given a deal in return for his testimony,” Shore testified at an evidentiary hearing, “and I don’t know what was represented at trial precisely, but had [trial counsel] contacted me before or even during the trial, I think [he] would have been very surprised to learn what I knew about Mr. Fuentes and Detective Deyne.”

On April 8, 1993, McKee vacated Martinez’s conviction based on ineffective assistance of counsel and trial error. McKee said he had been wrong to prevent Scott from questioning Fuentes about the murder charge. The judge explained that he mistakenly thought it was needless character evidence, rather than an avenue for exploring Fuentes’s need to cooperate with the police. The Superior Court reversed that ruling on November 24, 1993.

Three times—in 2000, 2004, and 2008—Martinez filed claims for relief under Pennsylvania’s Post Conviction Relief Act. As part of those claims, Martinez submitted affidavits supporting an alibi, that he was in Puerto Rico on February 19, 1985. He was able to provide health and housing records, as well as the school records of his children, to show his residency.

Each claim was denied and the trial court’s rulings were affirmed by the state’s appellate courts.

In 2016, Martinez moved his appeals to federal court, filing a pro se petition with the assistance of a fellow inmate for a writ of habeas corpus in U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania. His claim was quickly denied as untimely. In November 2017, he tried to expand his petition to allow greater latitude in making a claim of actual innocence.

The state’s response was handled by Banafsheh Amirzadeh, an attorney in the federal litigation division of the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office. As part of the review, she pulled the police department’s file on the Camacho case. She discovered that most of the file, including the detailed investigation into Santiago and the witness statements pointing to him as a suspect, had not been disclosed to Martinez or his attorneys. Included in those documents was a brief pre-trial discovery transmittal letter from the DA’s office to Martinez’s attorney that did not mention any of these files. Supporting the assertion of a lack of disclosure was the fact Martinez did not present a third-party culprit defense at trial, and there was no mention of Santiago in any of the post-conviction appeals.

This information was given to Martinez on December 13, 2018, and Jonathan Feinberg was appointed to represent him in a new habeas petition, which was filed on November 5, 2019. During this time, District Attorney Larry Krasner’s Conviction Integrity Unit, led by Patricia Cummings, took over the inquiry into the case.

In the new habeas petition, Feinberg wrote: “The upshot is this: Mr. Martinez stands convicted of a double murder based on a weak prosecution case despite possessing a credible alibi which was never presented to a trial judge who already had serious questions about Mr. Martinez’s guilt, all while an abundance of favorable evidence was hidden in police files for thirty years. With this background, Mr. Martinez’s conviction and sentence cannot stand.”

As part of its review, the CIU obtained a court order allowing the grand jury proceedings to be unsealed and disclosed to Martinez. They provided further evidence of the seriousness of the police investigation into Santiago.

Separate from his federal petition, Martinez filed a new petition for relief through the Pennsylvania courts. The DA’s office said in its response to that petition on October 16, 2020:

“Despite a clear obligation to provide this exculpatory evidence to Martinez prior to his trial, it was suppressed for decades and disclosed for the first time in late 2018. The Commonwealth agrees that the record in this case entitles Martinez to relief.”

On October 23, 2020, Judge Tracy Brandeis-Roman vacated Martinez’s conviction. The DA’s office dismissed the charges that same day. Martinez, now 73 years old, was released from prison. He had been initially approved for a COVID-related emergency release on bail in April 2020, but the order from U.S. District Court Judge Mitchell Goldberg was retracted because of questions about whether there was an outstanding warrant for Martinez in Puerto Rico. The DA’s office later said there was no warrant.

Speaking at the hearing where the conviction was vacated, Martinez’s daughter, Damisela Santiago, told Brandeis-Roman: “Thank you for this gift,” she told the judge. “I can’t make up the time, but I can certainly make new memories, and good ones.”

– Ken Otterbourg

|