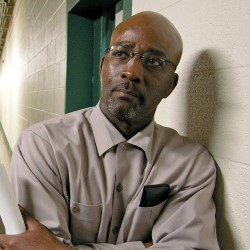

(Photo: USA Today)

Sarah Bost, a 54-year-old widow, was home alone. She told police that the perpetrator surprised her in the kitchen, put a knife to her throat, and demanded money. But there was none in her purse, and Bost said the man then dragged her to the stairs, ripped off her clothing and raped her. She would later say that she kept trying to look at the man’s face, but he kept pushing her head to the side and telling her “Don’t look at my face.” She said she fought back. A medical report would note that some of her fingernails were “nearly bent backwards.”

About 10 minutes into the attack, Bost’s phone rang. The assailant fled. Bost ran to a neighbor’s house, called 911, and was taken to Cabarrus Memorial Hospital. Along with treating Bost for the bruises and cuts she received in the attack, Dr. Lance Monroe combed her pubic area for hair samples and did a vaginal swab, in accordance with the emergency room’s rape protocols.

At the hospital, two officers with the Concord Police Department showed Bost a photo array of 13 Black men between the ages of 20 and 30 years old. Bost, who was white, did not make an identification. But in the officers’ report, she described her attacker as “a Black male, height, five foot, five to five foot nine, slender build, slim hips. Subject was plain spoken, used correct English and at times spoke very softly. No speech defect, accent or noticeable brogue evident. Subject was wearing a dark waist length leather jacket, blue jeans with a dark toboggan pulled over his head. Could possibly have been wearing gloves.”

Her initial descriptions included no mention of any facial hair. She would later describe her attacker as being “light-skinned” or “yellow,” or “not your normal black person.”

The Concord Police Department’s investigation of the crime scene turned up several pieces of evidence. They found burned out matches on the floor of a bedroom near the window ledge off the porch roof. They also found a shoe print on the banister, and investigators were able to lift an impression of it.

A few days after the attack, 20-year-old Ronnie Long became a person of interest in the investigation. At the time, Concord police knew that Long had been a suspect in an investigation of a similar rape and burglary in Washington D.C. in August 1975 after his Social Security card was found at the crime scene. (No charges were ever filed. The victim was unable to make an identification; Long’s attorneys would later say he had lost his wallet while visiting the city.)

Police arrested Long on April 29, 1976 and charged him with trespassing in the public park near his home, which was about a mile or so from Bost’s house. He came to the police station the next day to be fingerprinted and photographed. A report noted he wore a waist-length black leather jacket and black gloves, and that he kept his gloves on for most of his time at the station. The report said “He was able to do things as normal as someone without gloves. He was able to take out of his billfold his drivers [license].”

At the time, Long worked as a cement mason and lived with his parents. His court date on the misdemeanor trespassing charge was May 10.

Although Concord police had a photo of Long to show Bost, they decided on another route. They asked her to accompany them to the courthouse on May 10, telling Bost that the man who raped her might or might not be present. Bost sat in the second row, disguised with a red wig and sunglasses.

When Long’s case came up an hour or so later, he walked around to the defense table, wearing a flowered leisure shirt and a medium-length brown leather jacket. Even before Long spoke, Bost notified the officers that Long was her attacker. Later, at the police station, Bost picked Long’s photo out of an array. He was the only person in the array wearing a leather jacket.

Long’s trespassing charge had been dismissed, but the police showed up at his house a few hours later and told him he needed to return to the station to clear up a few matters. When he arrived, they arrested him and charged him with rape and burglary. For the next 44 years, he would remain behind bars.

When police searched Long’s family car in the station’s parking lot, they found a green toboggan and some gloves. Long said he had never seen the hat. They also found several matchbooks.

Long’s trial in Cabarrus Superior Court began on September 27, 1976, after a summer of demonstrations and protests surrounding his arrest. Prior to the voir dire of potential jurors, the Cabarrus County sheriff and other members of law enforcement reviewed a list of potential jurors and disqualified people from being called for jury duty. The county kept no record of the reasons for disqualification. The 49-person jury pool contained just two Black residents, and an all-white jury was seated for the trial. (At the time, Cabarrus County was approximately 20 percent Black.)

Bost testified that she was sure Long was her attacker, but her testimony differed from her earlier description and with Long’s appearance. Now, she said that her attacker wore a mustache. And she also continued to state that her attacker was light-skinned, although Long was dark-skinned.

Monroe testified about the severity of Bost’s injuries and his examination of the vaginal fluid. He was not asked and did not testify about any samples he collected.

During the trial, the state sought to introduce testimony comparing the burnt matches found at the crime scene with the matchbooks found in the Long family car. Long’s attorneys fought to suppress this evidence. With the jury not present, Long’s attorneys sought more information about the testing done on the matches. First, Detective David Taylor said the officers had taken the matches from the car because they were similar to those found at Bost’s house. When asked if they matched, he responded, “I didn’t match them, no sir.” Judge William Z. Wood asked, “Then they were not matched?” Taylor said that was correct. “In other words,” asked Wood, “the matches you got out of the car do not match with those found at the crime scene?” Taylor said, “I can’t testify to that.” Finally, Wood asked Taylor if he had any information about comparing the matches, to which Taylor replied, “No sir, they did not match.”

But with the jury present, Taylor repeated his claim that the matches he found in the Long family car were “of a similar nature” to burned matches found in Bost’s house.

Detective Van Isenhour also testified about the investigation of the crime scene and the processing of evidence. He said that he had processed the shoe print on the banister and then also made a print of Long’s shoes for comparison. He testified that on May 11, 1976, he had brought this evidence to the SBI crime lab. He was asked if that evidence had ever left his possession or control. He replied that it hadn’t. He also said that Taylor had given him other evidence, including a leather jacket, the green hat, and the matches. He testified that the jacket had also never left his control. He made no mention of this evidence being tested.

Dennis Mooney, the SBI’s print expert, testified about the footprints. He told jurors that the print on the banister “could have been made” by Long’s shoe, but he was not sure and it was not a “positive identification.”

Long did not testify, but he presented a strong alibi for the night of April 25, which was a Sunday. Witnesses said he had attended a meeting to plan a class reunion until about 8 p.m. He then went home from around 8:30 to 10 p.m., before leaving for a party in Charlotte, about 25 miles away. Witnesses said that while he was at home, he talked on the phone with his mother, his two-year-old son and the boy’s mother. People who saw him at the party testified that he had no bruises or signs of a struggle on his body. They also agreed that he was wearing khakis, not jeans, at the party and the reunion meeting, because at least one witness said he was at both events and made fun of Long’s attire. In addition, the witnesses said they never saw Long wear a toboggan. He favored leather hats.

In closing arguments, the prosecutor said, “We have shown that Ms. Bost’s testimony is not only accurate, but totally consistent with every piece of physical evidence existent. Everything she says happened that is capable of being corroborated by physical evidence ... is so corroborated.”

When Long’s attorneys argued there was no physical evidence that connected Long to the attack, prosecutors responded by saying that the absence of this evidence showed the honesty of the police, because it would have been easy for officers to rub Long’s clothing against the banister and put paint on the garments.

Rioting broke out in Concord after the jury convicted Long of burglary and rape on October 1, 1976. At the time of Long’s arrest, a rape conviction carried a mandatory death penalty in North Carolina, but the U.S. Supreme Court had struck down the state’s overly broad death penalty on July 2, 1976. He was sentenced to life in prison.

Long’s first appeal claimed that Bost’s pre-trial identification was “impermissibly suggestive” because of flawed practices by the Concord Police Department. He also said the police searched his car without consent and that the shoe print testimony should have been excluded. The North Carolina Supreme Court rejected his appeal in 1977.

In 1986, Long filed a Motion for Appropriate Relief, again arguing that the car search was illegal. Long also claimed that the jury selection was improper and racially biased. In addition, he said his attorneys had been ineffective in failing to adequately challenge the jury’s composition. The North Carolina Supreme Court denied his motion in 1988.

Long then moved his appeals to federal court, raising many of these same issues in his first petition for a writ of habeas corpus. That petition was denied in 1990.

On April 20, 2005, the North Carolina Center for Actual Innocence filed a motion on Long’s behalf asking a superior court judge to order the SBI, the Cabarrus County District Attorney’s Office, and the Concord Police Department to turn over all records and evidence collected in the case. The court granted the motion on June 7, 2005, and also ordered the hospital to turn over any records.

At a hearing a week later, the SBI said the only evidence it knew about was the shoe print. The police said they had a master case file, but the district attorney said a review of that file found “nothing of evidentiary value.”

The records released by the hospital included Monroe’s report, which showed a release form signed by Bost allowing the hospital to turn over pubic hair samples and a test tube of vaginal samples to the Concord Police Department. An officer signed the form, stating that he had received the evidence.

Although the district attorney had downplayed the value of the master file, it contained significant information about the investigation and the evidence collected.

The files showed that Isenhour had created two evidentiary reports, one undated and the other dated May 12, 1976. The undated report said that Isenhour had only taken the shoe prints to the SBI, while the other evidence had been held for further “investigative uses.” The May 12 report told a different story, stating that 14 pieces of evidence – clothes from Bost and Long, hair samples, carpet samples, and paint chips – were taken to the crime lab.

Six months later, the SBI turned over the evidence reports to Long’s attorneys.

The reports said that the hair found at the crime scene was different from Long’s and more reddish in color. It also said no hair consistent with Long’s was found in Bost’s clothing, and Long’s clothing showed no paint or carpet fibers similar to the samples from Bost’s house. In addition, the report said that four of the five matchbooks found in the car were of a different color than the burnt matches found at the crime scene. The fifth lacked sufficient identifying characteristics, but the analyst said the burnt matches “probably didn’t originate from this matchbook.”

In addition, the report made clear that Isenhour had not testified truthfully. He said the only evidence he had taken to the SBI was the shoe print, and that it had never left his control. In fact, the SBI had kept all the evidence that Isenhour brought for eight days.

These SBI reports and related documents became the basis of a second Motion for Appropriate Relief Long filed in 2008, claiming that he was entitled to a new trial because the state had failed to turn over exculpatory evidence to his attorneys.

This requirement is based on the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1963 ruling in Brady v. Maryland. To win a new trial based on a Brady violation, a defendant must show that evidence was not disclosed, that it was favorable to the defendant, and that its disclosure had a reasonable probability of changing the verdict.

During an evidentiary hearing on the motion, the prosecutor at Long’s trial said he had never seen the SBI reports, and that if he had, he would not have allowed Isenhour to testify in the manner that he did.

But the state pushed back on Long’s Brady claims, arguing that the SBI reports that failed to connect him with the crime were inconclusive, rather than exculpatory, and were therefore immaterial. In addition, prosecutors noted that Long’s attorneys had plenty of opportunity to ask Monroe and the police officers about whether other tests had been performed. But they didn’t, and the state shouldn’t be penalized for a defense attorney’s trial strategy.

During the hearing, James Fuller, one of Long’s trial attorneys, said that the reports would have played a powerful role in undercutting Bost’s testimony.

“I got one test here that does not implicate you,” he said. “Okay. I’ve got a second test that does not implicate you. And now the jury is paying attention. And now I’ve got a third test and a fourth test, and pretty soon it creates a snowball effect that you’re not the defendant. And that’s why I believe every one of those tests was critical.”

On February 20, 2009, Judge Donald Bridges of Cabarrus County Superior Court denied Long’s Motion for Appropriate Relief. He said there was no proof that the police or the district attorney’s office had ever received Monroe’s report, and that the defense had failed to ask Monroe any questions about his examination of Bost. Bridges wrote that the SBI lab reports didn’t provide meaningful analysis, which meant the state’s failure to disclose wasn’t a Brady violation.

Jurors, Bridges said, had a chance to examine the evidence, if not hear about the reports, and that not all of the undisclosed evidence was beneficial to Long. “The cumulative effect of any items with any value is so minimal that it would have had no impact on the outcome of the trial.”

Long appealed this ruling to the N.C. Supreme Court, which has seven justices. Justice Barbara Jackson was elected in 2010, after oral arguments had been held, and she took no part in the decision released on February 4, 2011. The remaining six justices deadlocked, affirming the lower court’s decision by default.

Long then began a second series of appeals through the federal courts. He filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus in U.S. District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina in 2012 that was dismissed because he had not obtained pre-filing authorization.

After that dismissal, Long’s attorneys contacted the North Carolina Innocence Inquiry Commission, a state agency that investigates and makes recommendations on claims of innocence. As part of the commission’s initial review, it obtained 43 fingerprints – previously undisclosed, even after the 2005 order – that had been lifted from the crime scene by investigators with the Concord Police Department. Long’s fingerprints were excluded as contributors. Four of the prints were of sufficient quality to run through state and national databases. The Concord police said its comparison returned “no possible contributors,” but declined to state which databases they had queried. While Bost, who died in 2015, had testified that her attacker wore gloves, the burned matches suggested the attacker had taken them off at some point during the crime because it would be difficult to strike a match while wearing gloves.

The vaginal samples collected by Monroe were never located. Because of a lack of DNA evidence in Long’s case, the Innocence Commission decided not to pursue further investigation.

Now represented by attorneys with Duke University’s Wrongful Convictions Clinic, Long filed a third petition for a writ of habeas corpus in 2016. This petition said that the fingerprints were new evidence of innocence, part of a legal strategy to allow Long to get around the limitations on successive appeals, although later federal court rulings said that Long needed first to litigate the fingerprint claim in state court.

The petition argued that Bridges had erred in weighing the materiality of the state’s Brady violations and that Bost’s initial identification of Long was inherently flawed. His attorneys said there had been no need to bring her to the courthouse, where Bost waited nervously in disguise while a stream of Black men charged with crimes paraded past.

“Holding the procedure in a courtroom further enhanced the likelihood that the victim would select someone despite his possible innocence, because the courtroom itself conveys a message that the persons present were criminals,” the petition said. While Bost later selected Long from a photo array 20 minutes after the courtroom identification, Long’s attorneys said that selection was contaminated because Bost was “primed” to pick Long.

Long’s petition was independently supported by dozens of attorneys, legal scholars and criminologists, whose brief provided context about the challenges of eyewitness identifications and the forensic evidence at the heart of the appeal.

The petition argued that Bridges’s ruling ran counter to federal law by trivializing the importance of the undisclosed evidence. Although this evidence didn’t directly exonerate Long, the petition said that it was exculpatory, and that it discredited the police investigation and impeached the state’s witnesses. Equally important, the petition said, it was the obligation of prosecutors to turn over this sort of evidence. The burden does not rest on defense attorneys to ask whether it existed.

U.S. Magistrate Judge L. Patrick Auld recommended denying Long’s petition on May 22, 2018. While his findings acknowledged significant legal errors by Bridges in his interpretation of what constitutes exculpatory evidence, Auld agreed that the evidence wasn’t sufficiently material to have made a difference at trial. He said Bost’s identification was strong and decisive, and while her initial identification was “unorthodox,” Long’s attorneys couldn’t point to how it violated Long’s rights as a defendant. The district court adopted Auld’s recommendations. Long appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, where a three-judge panel heard arguments in March 2019.

By a 2-1 vote, the appellate court rejected Long’s appeal on January 8, 2020. In the majority opinion, written by Judge Julius Richardson and joined by Judge Paul Niemeyer, the court said that Bridges had not been unreasonable in how he viewed the materiality of the undisclosed evidence. The opinion said that most “jurors would consider the impeachment evidence peripheral.” The opinion also said that Congress had created a necessary high bar for defendants seeking relief in federal court, placing “great weight on the values of federalism and finality.”

Judge Stephanie Thacker wrote the dissent. She noted that Bost’s identification was neither as strong nor as consistent as previous courts or her colleagues had ruled.

While the majority opinion said that Isenhour had offered an “incomplete picture of the testing he requested,” Thacker was more pointed. She wrote: “In short, he lied. Repeatedly.” (Isenhour pled guilty to possession of a stolen U.S. Treasury check in 1987 and was sentenced to four years in prison.)

Thacker criticized prosecutors for arguing during the years of appeals that Long’s attorneys should have tested the material themselves or asked the state’s witnesses whether items had been tested.

“This argument is nonsensical and offensive. Such an argument completely turns the burden of proof in criminal cases on its head. Again, I am shocked as to the apparent need to educate the state that the burden of proof in criminal cases rests with the state, and remains with the state throughout the course of the trial.”

She closed by writing, “In this circumstance, Appellant must prevail. To hold otherwise would provide incentive for the state to lie, obfuscate, and withhold evidence for a long enough period of time that it can then simply rely on the need for finality. That, I cannot abide.”

Because of the split decision, Long petitioned the Fourth Circuit court for what is known as an en banc review of his case. (Less than 1 percent of these requests are granted.) On August 24, 2020, the judges, by a 9-6 vote, reversed the dismissal of Long’s petition.

Now in the majority, Thacker wrote: “A man has been incarcerated for 44 years because, quite simply, the judicial system has failed him. Rather than overstepping our judicial role, as the dissent contends, today we remain faithful to our oath by 'administer[ing] justice.'”

Judge Catherine Eagles of U.S. District Court granted Long’s petition for a writ of habeas corpus on August 27, 2020, and he was released from prison that day. The Cabarrus County District Attorney’s Office dismissed the charges on August 28.

Long married in 2014, and he told CBS News that he wanted to spend time with his family and his son. He said he wanted to visit the graves of his parents, long dead. “I know my mother and father died with a broken heart. I’m gonna tell them now, when I visit the gravesite, ‘Your son is clear.’”

After the dismissal, Long sought a pardon of innocence from Gov. Roy Cooper, which would allow him to receive compensation for his wrongful conviction. Cooper served as attorney general from 2001-2017, and his office played a key role in representing the state during Long’s unsuccessful appeal of the order denying his 2008 Motion for Appropriate Relief.

On December 17, 2020, Cooper issued the pardon of innocence. In March 2021, Long received a check from the state for $750,000, the maximum amount allowed under North Carolina's wrongful conviction law.

Long criticized the amount, noting it worked out to about $17,000 for each year he was wrongfully imprisoned. On May 3, 2021, he filed a federal civil-rights lawsuit seeking additional compensation from the City of Concord and current and former members of its police department. The lawsuit was later amended to include the State of North Carolina, for the role the State Bureau of Investigation played in Long's wrongful conviction.

On January 8, 2024, Long reached a settlement with the City of Concord, which agreed to pay him $22 million. Separately, the state of North Carolina agreed to pay him $3 million.

The Concord City Council said in a statement: “We are deeply remorseful for the past wrongs that caused tremendous harm to Mr. Long, his family, friends, and our community. Mr. Long suffered the extraordinary loss of his freedom and a substantial portion of his life because of this conviction. He wrongly served 44 years, 3 months and 17 days in prison for a crime he did not commit. While there are no measures to fully restore to Mr. Long and his family all that was taken from them, through this agreement we are doing everything in our power to right the past wrongs and take responsibility. We are hopeful this can begin the healing process for Mr. Long and our community, and that together we can move forward while learning valuable lessons and ensuring nothing like this ever happens again.”

– Ken Otterbourg

|