CBS News

Marshall flagged down a passing motorist and was taken to University Hospital and told police that Williams, who was 30, was still at the apartment. By the time police arrived, around 2:30, a crowd had gathered near the apartment. Many of these people had been at a party just up the street when they heard shots being fired, which was not unusual in the neighborhood. Police found Williams’s body inside the apartment and began canvassing the crowd for witnesses.

Hubert Nathan Myers, known as “Nate,” approached the officers. He said he had been at the party and lived in the second bedroom of the apartment. He went inside with the police, and when he saw the body, he cried out, “My God, it’s Baldie,” using a nickname for Williams.

Marshall had been shot twice in the neck and once in the left arm. While she was at the hospital, she told officers that she and Williams had been shot by two men who stood at the foot of the bed, and she identified one of her shooters as Clifford Williams Jr., who was not related to Jeanette Williams. He was 33, owned a pool hall and was a known heroin dealer. Marshall was an addict and an on-and-off customer, and she said Williams had shot them over a $100 debt for rent he paid on their apartment.

Clifford Williams was in the crowd while police worked the crime scene. He was quickly arrested at about 3 a.m. As he was being taken away, he yelled out for someone to call his attorney and get a list of the partygoers who could give him an alibi. Ten minutes later, the hospital radioed again. Marshall had named the second shooter, Nathan Myers, who was also Clifford Williams’s nephew and managed the pool hall. Marshall said she had then seen both of them on the street after she staggered outside. Myers, who was 18 and had no violent criminal record, was also arrested that evening. Both men were tested for gunshot residue a few hours later. The tests came back negative.

Many of the 40 or so attendees were lesbians, part of a tight-knit group that were close friends with Jeanette Williams. In statements to the police taken during the next month, all of them remembered Williams and Myers being at the party, and nearly all of them said the men had been there when the shots were fired.

The bedroom where the women were shot was very small, nine feet by twelve feet, with the bed taking up most of the space. The space at the foot of the bed was cramped and hard to get to. The initial investigation also found holes in the window curtains and screen, a deformation with a “carbonaceous material” in the frame, and broken glass on the bed, suggesting the shots came from outside. But the investigating officers dismissed that scenario because it clashed with Marshall’s statements. Instead, they wrote, “it appears as though the suspects in this case intended to make it look as though the victims had been shot by someone from the bedroom window.” The officers would also note in their report that the “physical evidence at the scene is entirely consistent with the … statements of the victim.”

In addition, although Marshall claimed there had been two shooters and two guns firing until their chambers were empty, only six fresh bullets were recovered from her and Williams. They were all .38 caliber. A .32 slug was also recovered from Williams, but it was covered in scar tissue, indicative of an old wound.

Myers and Williams were each charged with murder and attempted murder, with Williams facing the death penalty if convicted. Prosecutors tried to cut a deal with Myers, promising him either two years (his account) or five years (the prosecutor’s account) if he pleaded guilty and testified against his uncle. He declined.

Their first trial began in late July 1976 and ended in a mistrial. Their second trial began September 1, 1976. It lasted two days. The state had six witnesses and presented no forensic evidence, relying instead on the testimony of Marshall to place Williams and Myers in her bedroom during the shooting.

At the time, Florida courts allowed defense attorneys to make the final closing argument if they waived calling their own witnesses. The men’s attorneys used this strategy. The jury didn’t hear about the alibis, the glass fragments on the bed, the holes in the window screen, or the failure to find evidence of a second gun. When one of the defense attorneys recalled an evidence technician to discuss testing the defendants’ clothes for blood (and finding none), the technician also noted he had swabbed their hands to test for gunpowder. But the attorney never asked about the results of those tests.

Both men were convicted. Myers was sentenced to life in prison, with parole possible after 25 years. The prosecution asked for the death penalty for Williams, but the jury recommended a life sentence for William. However, the trial judge overruled the jury ‘s recommendation and sentenced him to death. In 1980, the Florida Supreme Court reduced his sentence to life, also with parole possible after 25 years.

Myers had challenged his conviction several times, first in 1987 and then later in 2014. Both appeals were denied.

In early 2017, Myers read a newspaper article about the formation of a Conviction Integrity Unit in the State Attorney’s Office for the Fourth Judicial Circuit, which includes Jacksonville and Duval County. He quickly wrote to State Attorney Melissa Nelson, asserting his and his uncle’s innocence based on four key points: First, were the numerous alibi witnesses who had not been called at trial; second were the results of the gunshot residue tests; third was the gunshot residue on the window frame and other forensic evidence suggesting the shooting had come from outside the bedroom; and fourth was the insufficiency of Marshall’s testimony.

In a follow-up letter, Myers included a copy of the ballistics report and a surprising piece of potential new evidence: A man named Nathaniel Lawson had confessed to the crime before he died in 1994.

The Fourth Circuit CIU began a re-investigation of the case. There were several complications. Marshall had died in 2001, as had several potential alibi witnesses. But the forensic evidence was powerful. Along with the apparent bullet holes in the window and the frame, a more thorough examination of the wounds on Williams and Marshall indicated they had been shot from the side, not from the foot of the bed, which also supported the theory of an outside shooter. The medical examiner’s report had noted a lack of gunpowder residue on Williams or the bed sheets. That would have been unlikely if the shots had come from close range in the tiny room. The CIU also did an audio test that revealed that only shots fired from outside the building would have been loud enough to have been heard at the party, approximately 150 feet down the street.

In the immediate days after the shooting, there was talk that a neighbor across Morgan Street had seen a man shooting from outside the women’s bedroom window. Police interviewed several people who told them what this man had said he had seen. They interviewed the man, who denied seeing the shooting. However, he failed a polygraph test that asked him whether he was telling the truth about his denials. According to the CIU’s report, prosecutors didn’t mention any of this in their discovery items.

The CIU investigators spoke to four people who said Lawson had confessed to shooting Williams and Marshall. One said that Lawson told him the shooting was at the behest of a drug dealer who was upset at Marshall’s failure to pay a debt. Another of the four was Frank Williams, the brother of Clifford Williams. He said that he reached out to Lawson after hearing rumors of his involvement. They met in the parking lot of a church, and Lawson said he had shot Williams and Marshall because “she was stealing from me and I had to send a message.” He didn’t say who he was referring to. After Lawson died, Frank Williams took this information to an attorney, who told him that there was little to be done.

The police report places Lawson near the apartments after the shooting. After Williams and Myers were arrested, Williams’s wife, Barbara, was stopped leaving the scene in a pickup, as police were concerned that the murder weapon might be in the vehicle. The report mentions Barbara Williams and a man named Rico Rivers in the truck but didn’t identify the other two passengers. But when Barbara Williams was deposed in 1976, she said Lawson was with her.

In its report, the CIU said that Myers and Williams had been convicted in part due to confirmation bias by the police. “While the police had probable cause to arrest the defendants,” the report said, “the inconsistencies in Victim Marshall’s accounts, the changes to and evolution of her testimony, and the evidence available over the course of this case was sufficiently significant to call the prosecution’s attention to the weakness of their premise.”

The men also were victims of ineffective counsel, the report said. Their attorneys failed to call any alibi witnesses or introduce physical or forensic evidence to challenge the state’s theory of the crime. While they cross-examined Marshall and suggested that she might have misidentified her shooters because she was starting Methadone treatment and had smoked marijuana a few hours earlier, they never challenged her essential version of events. “The reality was that Victim Marshall could not have seen the perpetrator who shot through the bedroom window,” the report said, “and would not have known that person’s identity. That was the crux of the case and yet it was never argued to the jury.” Importantly, Florida no longer allows defense attorneys to waive calling witnesses in exchange for getting the last word.

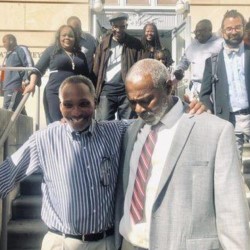

Florida law doesn’t allow prosecutors to directly vacate convictions. Krista Dolan and Seth Miller of the Innocence Project of Florida represented Myers, and Buddy Shultz of Holland & Knight represented Williams in their motions to vacate, which relied on the findings of the CIU report. Circuit Court Judge Angela Cox granted the motions on March 28, 2019, and after 42 years in prison for a crime they didn’t commit, Myers, now 61, and Williams, now 76, were released.

According to the Florida Times-Union, Myers said after the ruling, “I’m not bitter for what happened to me because the Lord Jesus Christ made me to be a man. I was a kid when I came to prison. I grew up on my own, so I understand the things a man (ought to) do. What I want to do now is have a chance to go out and be that man.”

Myers received $2 million in state compensation in early 2020. Williams, because of a previous felony conviction, was ineligible under Florida law. However, in June 2020, Gov. Ron DeSantis signed legislation approving a $2 million award to Williams.

On January 11, 2024, Williams died of cancer.

– Ken Otterbourg

|