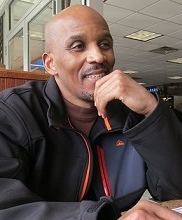

Scott Lewis (Photo: New Haven Independent)

Police recovered bullets and casings that were later determined to be from a .357-caliber semi-automatic pistol.

A month later, an informant told New Haven police that a man named Michael Cardwell had admitted murdering Turner and Fields. However, no evidence could be found to corroborate the informant’s information.

After nearly three months of intensive work, during which 34 police reports were filed and more than 25 witnesses were interviewed, the case remained unsolved. A $20,000 reward was offered but produced no leads.

In early January 1991, the original detective in charge of the investigation transferred to another position, and Detective Vincent Raucci took over. He solved the case in three days.

In April 1991, 25-year-old Scott Lewis and 21-year-old Stefon Morant, two alleged drug dealers, were charged with the murders based on a statement from Ovil Ruiz, as well as three other witnesses—Hector Ortiz, Jose Roque, and Milly Martinez.

Raucci said Ruiz told him that several weeks after the shooting, he overheard Lewis and Morant discuss how they committed the murders. Ruiz later expanded on his statement to say he was in a car with Lewis and Morant on the night of the murders. He said he waited in the car while Morant and Lewis went into the apartment. Ruiz said he heard gunshots. Raucci said that Ruiz said Turner and Fields were murdered because Turner had tried to run off with drug money that belonged to Lewis.

Ruiz also claimed that a week or so after the murder, he was on a basketball court in Criscuolo Park with Roque when they saw Lewis drive up and park his car more than 700 feet away. Ruiz claimed he saw Lewis take a package from his trunk–an object that he recognized as a handgun, although, according to Ruiz, the object was wrapped in white plastic. Ruiz said he could tell the plastic bag was a “Stop and Shop bag” because of its red lettering.

This story was tracked by Roque, under Raucci’s questioning the day after Raucci obtained the statement from Ruiz. In a statement that Roque later recanted at Morant’s trial, Roque gave the same account of seeing Lewis dispose of the murder weapon while supposedly with Ruiz and Morant on the basketball court 700 feet away. Roque had claimed he could tell that the gun was a .357-caliber pistol--the caliber already known by the police to be the murder weapon--because (at that distance) he could see the barrel “had a big hole.”

Within 24 hours after obtaining the statement from Roque, Raucci proceeded to obtain a statement from Morant. The statement was a 20-minute audio-recorded interview that followed four hours of unrecorded interrogation. Morant recanted the statement almost immediately and said Raucci had manipulated him, fed him details, and threatened the death penalty. At the time of the interrogation, Morant said he was intoxicated after consuming alcohol and smoking marijuana.

In the recorded statement, Morant said Lewis had picked him up at Chucky’s restaurant in Fair Haven, Connecticut, to give him a ride home. But he instead first took a detour, miles out of the way, to Howard Avenue. There, Lewis left him to enter a building and returned a short time later with a sweaty and agitated demeanor. Morant said Lewis then drove him back to Fair Haven to drop Morant at his home. Morant said that Lewis had “done what he had to do.”

Morant also repeated the account of the Criscuolo Park long-distance sighting of Lewis disposing of the murder weapon, in yet another Raucci-procured variation of that observation. Although the statement Raucci took from Morant accused Lewis of committing the Turner-Fields murders, Morant also stated on the tape that he did not believe Lewis had ever committed any murders.

At the completion of taping, Morant refused to sign the statement. Raucci then drove Morant home, making a detour to Howard Avenue, where he pointed out Turner’s apartment building. Morant and his mother returned to the New Haven police detective bureau the next day, and sought to recant his statement. Police threatened to charge him with conspiracy and turned him away.

Raucci also obtained a statement from Milly Martinez, who said she was on the street outside of the location of the murders. She said she heard the gunshots and saw Ruiz in the car. Raucci also got a statement from Ortiz saying that Lewis and Turner were homosexuals and romantically involved with each other.

In 1996, Ruiz, Ortiz, Roque, and Martinez recanted their statements as false and the product of coercive interviews by Raucci.

Morant went to trial in 1994 in New Haven County Superior Court. The prosecution’s case rested primarily on Morant’s statement and the testimony of Ruiz and Raucci. According to Ruiz, after Morant and Lewis came out, they slapped hands and Lewis said, “Yo, man, I did what I had to do, you know what I am saying?”

On June 8, 1994, a jury convicted Morant of two counts of first-degree murder, and he was sentenced to 70 years in prison.

Lewis was convicted on May 10, 1995, based primarily on the testimony of Ruiz and Raucci. The defense attempted to introduce evidence that within a month of the shooting, the informant told detectives that Cardwell had confessed that he and his brother, Vincent, had killed Turner and Fields, but the trial judge refused to allow the evidence to be heard.

Lewis denied involvement in the shooting and witnesses said he was at work at a printing company at the time of the killing. The jury convicted him of two counts of first-degree murder, and he was sentenced to 120 years in prison.

A year later, Ruiz gave a statement to the FBI as part of a federal investigation of Raucci, police corruption, and the Turner-Fields murder investigation. Ruiz said that Detective Raucci had coerced him to testify against Lewis and Morant because Raucci was secretly involved in dealing drugs and wanted to eliminate Lewis and Morant as competitors. Ortiz and Martinez also were interviewed and recanted their statements, saying that Raucci threatened them and fed them the details to repeat on tape. Roque repeated his recantation as well.

Lewis and Morant attempted to win new trials based on Ruiz’s statement, but their efforts were unsuccessful. Raucci denied any involvement in drug trafficking.

Over nearly two decades, both men sought to overturn their convictions without success. Lewis filed a federal petition for a writ of habeas corpus in 2003 and a hearing was held 10 years later in the summer of 2013. The petition presented the testimony of Michael Sweeney, a New Haven police lieutenant who had been one of Raucci’s supervisors. Sweeney had retired in 1998 and spent a year working as a police officer for the United Nations in Bosnia.

Upon his return, he reached out to Morant’s defense attorney after reading in a local newspaper that Raucci had resigned from the New Haven police department because of misconduct. The article noted that Raucci had been linked to the New Haven drug trade and charged with larceny following an internal police investigation. He was also arrested for a domestic violence incident. He fled Connecticut when he was charged in the domestic violence incident, and the FBI arrested him after a four-hour standoff in New Mexico.

Sweeney revealed that he had been present during significant portions of Raucci’s interrogation of Ruiz back in 1991. Sweeney said that he interviewed Ruiz alone for more than a half an hour, and Ruiz told him that he knew nothing about the crime. Raucci then joined Sweeney and they interviewed Ruiz together. Ruiz continued to insist that he knew nothing.

Sweeney said that Raucci then began giving Ruiz facts about the case. Sweeney told Raucci to leave the interrogation, and in the hallway told him to stop feeding details. Raucci and Sweeney then again confronted Ruiz. Raucci then told Ruiz that he wanted Ruiz to tell him that he was driving the car the night of the murders, and that even though there was a warrant for Ruiz’s arrest, he could leave if he cooperated. At that point, Ruiz began to change his statement and Raucci began to give Ruiz additional details. Sweeney took Raucci out in the hall a second time and told him to “knock it off.”

At that point, Sweeney, who was the shift supervisor, had to attend to another matter and left Raucci and Ruiz alone. Not long after, Raucci emerged with a statement from Ruiz saying that he had been driving the car that night. The statement also said that he, Morant, and Lewis got two guns and drove to the apartment. While Ruiz waited, they went inside and there were gunshots. Afterward, the statement said, they came out and drove away.

Sweeney confronted Raucci again. He told Raucci to step out of the room and then Sweeney confronted Ruiz alone, asking if he was telling the truth. Ruiz admitted that he was lying and that all the information came from Raucci. Sweeney then ordered Raucci to re-interview Ruiz. Ultimately, Raucci emerged with a statement that Ruiz was saying that although he wasn’t present, he had overheard Lewis and Morant discussing the murders.

Sweeney testified that when he later learned that Lewis and Morant had been charged with the murders, he told a supervisor that Ruiz was a liar and that the case should not be based on his testimony. However, nothing came of the comment, and no record of any of this was made by Sweeney or the supervisor to whom he had spoken.

In December 2013, U.S. District Judge Charles Haight Jr. granted the writ, vacated Lewis’s convictions, and ordered a new trial. Haight ruled that Lewis’s defense lawyer should have been informed of the exculpatory Sweeney evidence concerning Ruiz and Raucci. Judge Haight said the defense lawyers should have been told that “Sweeney heard Ruiz deny three times, in the manner of St. Peter in a different context, any knowledge of the Turner-Fields murders, only to emerge, after being closeted with Raucci, as the State’s key fact witness against Lewis and Morant.”

Lewis was released on bond on February 25, 2014, while the New Haven District Attorney’s Office appealed the decision. In May 2015, the Second Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals upheld Haight’s ruling.

In June 2015, a judge granted a motion filed on behalf of Morant to reduce his sentence from 70 years to 25 years. Morant was immediately released.

On August 5, 2015, the charges against Lewis were dismissed. Lewis filed a federal civil rights suit in August 2016 seeking damages from the city of New Haven. The lawsuit was settled in 2017 for $9.5 million.

Meanwhile, attorney Ken Rosenthal sought a pardon for Morant, submitting a lengthy account of how Raucci had framed Morant and Lewis by coercing a false confession from Morant and obtaining false statements from Ruiz, Ortiz, and Roque.

Rosenthal noted that the Connecticut Innocence Project had represented Morant during unsuccessful post-conviction proceedings and that DNA testing of blood samples taken by the police at the scene of the murders failed to link Lewis or Morant to the crime.

In addition, a forensic examination by the FBI of the tape of Morant’s statement showed that Raucci had stopped, started, and over-recorded the tape nine times in the 19-minute taping. A similar examination of Roque’s recorded statement showed that Raucci stopped and restarted the tape 14 times in the course of a 20-minute interview. The examination supported statements by Morant and Roque that Raucci kept stopping, rewinding, and restarting the tape until they made the statements that Raucci wanted.

The pardon application cited how Morant had obtained employment, starting with hard labor and ultimately becoming employed by the city of New Haven Department of Public Works. In addition, Morant also worked as a case manager counseling ex-offenders transitioning from prison, as well as a recovery coach for mentally-disabled men reintegrating into society following in-patient hospitalization.

“Stefon Morant has become as much, if not more, of a contributing member to society and positive influence on those around him as any of the Connecticut exonerees who, unlike Stefon, have received formal acknowledgement of their wrongful convictions and erasure of their records,” Rosenthal said in the pardon application. “In fact, given the circumstances of his case, it is a testament to this now 52-year-old man that he has had the strength and wisdom to forswear bitterness, self-pity or negativity that would surely have been understandable, and to instead engage in the productive endeavors he has undertaken from the very inception of his release.”

On October 29, 2021, the Connecticut Board of Pardons and Paroles granted Morant an “absolute pardon.”

In a letter to Morant, the board declared, “Congratulations, as you are now legally able to truthfully state you have never been arrested or convicted of a crime in the state of Connecticut as it relates to any of the convictions pardoned.”

In 2023, the state of Connecticut awarded him $5,500,050 in state compensation.

– Maurice Possley

|