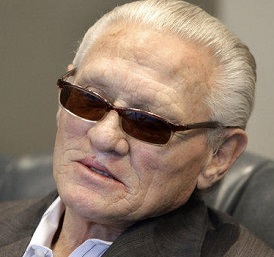

Billy Frederick Allen (Photo courtesy Los Angeles Times) On April 9, 1983, just past 4 a.m., a police officer was sent to investigate a possible shooting in University Park, an inner suburb of Dallas, Texas, at the residence of two narcotics traffickers, James Perry Sewell and Raven Dannelle Lashbrook.

The officer, Curtis Clary, found Sewell, gagged, handcuffed and covered with blood, standing near the duplex where he lived.

Sewell, 46, said he had been shot in the back of the head twice, slashed and robbed and that his girlfriend, Lashbrook, 33, had been kidnapped. Clary seated Sewell in the front yard and then, with another officer who arrived, went inside the house to look for suspects and other victims, but found none.

Emergency personnel arrived and loaded Sewell into the ambulance. Before they left, Clary came out and asked Sewell who had attacked him.

What then happened became a matter of dispute and would lead to the conviction of Billy Frederick Allen and, more than a quarter-century later, to his exoneration.

Clary later testified that Sewell said it was “Billy Allen, Bert (whose last name he did not know) and another white male.”

One of the paramedics would later say—but not until after Allen was convicted—that Sewell specifically said his attacker was Billy Wayne Allen. The paramedic said Sewell repeated the full name five times.

After the ambulance left, the officers searched the house once more and discovered Lashbrook’s body in a car parked in the carport. Four identifiable fingerprints were found—two from the house, one from one of Sewell’s cars and a fourth—a palm print—from the roof of the car in which Lashbrook’s body was found.

Police began conducting computer checks on the name “Billy Allen” and came up with a few possibilities, including a man named Billy Wayne Allen, who had a prior history of convictions for drug possession and violence, as well as Billy Frederick Allen, 37, who also had a history of violent crimes and drug convictions.

When the palm print was matched by police to the left palm of Billy Frederick Allen, an arrest warrant was issued and police went to the motel where they believed he was staying. But he was gone.

Allen was arrested in California on April 23, 1983 and he was charged with capital murder and attempted capital murder. On June 17, 1983, Sewell died and the charge of attempted capital murder was amended to capital murder.

Prior to trial, Allen’s defense attorney hired a private investigator who met with the University Park police chief as well as the lead investigator on the case. They gave the investigator the details of the investigation, including a two-page report filed by Clary detailing the events of the night of the murders. None of the information provided mentioned that Clary said Sewell had told him that “Billy Allen” was one of three men who committed the crime.

Allen went on trial before a jury in Dallas County Criminal District Court.

The prosecution’s primary evidence was Allen’s palm print found on the car containing Lashbrook’s body as well as the unexpected testimony from Clary that Sewell had said “Billy Allen” when questioned in the ambulance.

When Allen’s lawyer expressed surprise at the testimony, he was given a four-page police report. The first two pages were the same report the private investigator obtained before trial. But there were two additional pages that he had never seen before. On page three, the report detailed Clary’s account of Sewell’s statement in the ambulance.

The defense suggested that the couple had been murdered because of their involvement in drugs (Lashbrook was reputed to be a methamphetamine cook) and because the house had been thoroughly ransacked, as if someone were trying to locate drugs or money.

The defense admitted that Allen knew Sewell and had met with him a few days before the murders. They met at a café where Allen sold some gold scraps he had harvested from his used-goods store. Allen’s wife testified that Allen had rested his hand on top of the car while Sewell sat in the front seat and counted out the cash he paid Allen for the gold.

Allen’s attorney argued that the belatedly disclosed report had been made after the fact to bolster Clary’s testimony and that it was a lie.

During deliberation, the jury sent out two notes asking to reread Clary’s testimony regarding Sewell’s statement in the ambulance. Allen was convicted of both murders on September 14, 1983 and sentenced to life in prison.

After the trial, Allen’s lawyer sent the investigator out to see if there were any witnesses to the statement Sewell allegedly made to Clary in the ambulance and two paramedics who treated Sewell were located.

One said that Sewell did say “Billy Allen,” but he also mentioned a middle name that the paramedic could not recall. The other paramedic, Phil Castle, said he heard “Billy Wayne Allen” and that Sewell said it at least five or six times. Castle was adamant, saying he could “never forget that.”

Allen filed a state petition for a writ of habeas corpus in October 1984 raising the newly discovered evidence. That writ was denied because at that time actual innocence based on newly discovered evidence was not a proper subject for habeas review.

Allen’s direct appeal of his conviction was denied by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals on February 7, 1985.

In April 1992, Allen filed another petition for a writ of habeas corpus, alleging in part that the state had suppressed exculpatory evidence and that he had received an inadequate legal defense because his lawyer had discovered the evidence from the paramedics, but failed to file a motion for a new trial.

A hearing was held in December 1992 and the trial court recommended granting a new trial “in the interest of justice.”

Before the Texas Court of Appeals could rule on that decision, Allen filed another application for a writ in the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals in April 1993 and filed a supplement in April 1994, alleging “factual innocence” as an additional ground to set aside the conviction.

The Court of Appeals remanded the case for the judge to make specific findings. On remand, the trial court found that the defense attorney’s failure to investigate “constituted a lack of diligence that is not recognized as a basis for granting a new trial” and also rejected the factual innocence claim. The trial court recommended that the conviction stand and the Court of Appeals upheld the order in January 1995.

In February 1996, Allen filed another petition for a writ of habeas corpus, alleging his trial counsel was ineffective for failing to adequately investigate the case and to timely discuss the exculpatory evidence. That writ was dismissed in July 1996 as being duplicative of earlier petitions.

In May 2004, Allen filed a fourth petition, again raising inadequate legal defense and factual innocence. This was the first time that Allen had filed a writ following a decision in another Texas case in which the Court of Criminal Appeals recognized that actual innocence claims could be raised in a non-capital case.

By that time, Allen’s lawyers had obtained an affidavit from a man named Clifton Cook, who said that on April 10, 1983—the day after the murders—he purchased jewelry belonging to Lashbrook from Billy Wayne Allen and that Allen told him that he had “wiped a smart-assed-son-of-a-bitch named Perry in Dallas” for interfering in his business and that “Lashbrook wouldn’t be making any more dope” because “he had sent her back to Kentucky to her family and she will never come back.”

The trial court recommended that Allen’s conviction be set aside, ruling that the evidence of innocence was “so strong that (the court could not) have confidence in the outcome of the trial.”

On February 4, 2009, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals agreed, upholding the finding. The conviction was set aside the conviction and the court ordered a new trial.

Allen was released on bond on March 15, 2009.

On March 21, 2011, the day set for retrial, the Dallas County District Attorney’s Office dismissed the charges, saying that some of the evidence in the case had been destroyed with the knowledge of the prosecution, that one witness had since died and another had stopped cooperating. The prosecution declined to say Allen was innocent.

In May 2012, Allen received a lump sum $2,073,333 in state compensation and thereafter a monthly annuity of $15,463.

– Maurice Possley

|