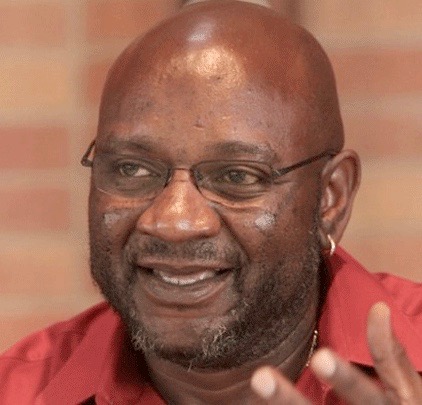

Darryl Hunt

“I just seen a lady with some guy jumping on her down here, you know,” he said.

The dispatcher asked the caller for more information but misunderstood his answers about the location of the attack and sent the police to the wrong part of the city.

It would be more than six hours later that a factory worker on his lunch break found the body of Deborah Sykes, who was 25 years old. She was lying on her side, naked from the waist down, in a field near a high-rise apartment building called Crystal Towers. Her autopsy said that Sykes died from multiple stab wounds and had been sexually assaulted.

Sykes worked as a copy editor for the Sentinel, the city’s afternoon newspaper, which closed a year later, typically starting work at about 6 a.m. and often parking her car a few blocks from the newsroom, not far from where her body was found.

As the Winston-Salem Police Department began its investigation, several witnesses quickly came forward to say what they had seen. William Hooper, who worked at the Hanes Dye & Finishing plant at the base of the hill that ran behind Crystal Towers, told police on August 10 that at about 6:20 a.m., he saw a white woman with two Black men along West End Boulevard. One of the men kissed the woman, the other, who was shorter, shook his fist at her. He didn’t think the woman was in trouble.

A few minutes later, Thomas Murphy took the same route on the way to the Hanes factory. In a statement to police, he said: “When I saw them they were leaning toward each other as if they were drunk … The Black male had his right arm around her neck and was holding her right hand in his left hand, and as I went by I saw another Black male about 100 feet down the street from them.”

Separately, the police also went to track down Mitchell, who purportedly made the 911 call. He had an extensive criminal record, including charges of assault and robbery. Detective Jim Daulton, the lead investigator, caught up with Mitchell and his friend, 19-year-old Darryl Hunt, a few days later. Daulton played a snippet of the 911 call to the men. It wasn’t Mitchell’s voice.

On August 22, police thought they caught a break in the case. They had received a tip that Sykes’s killer had just gotten on a city bus. The man providing the tip was named Johnny Gray, and he said he was also the person who called 911 on August 10.

Gray said he had seen the attack because after he heard a woman hollering, he looked over and saw a Black man straddling and hitting a white woman who was naked. Gray said he took off running, but not before he got a good look at the man.

Daulton and Detective Bill Miller brought Gray in to look at the man from the bus brought in for questioning. “Terry Thomas was sitting in a chair facing directly toward Johnny Gray,” Miller would later write in a police department internal review. “Gray and Thomas were approximately 15 feet away from each other. I don’t remember how he said it or acknowledged it, but in my opinion, Johnny Gray insinuated that the Black man in the interview room was the same Black man he had seen assaulting the white female near the bushes on West End Blvd.”

But Thomas was the wrong man. He had been in jail on August 10, awaiting trial on a trespassing charge. The police would later say at Hunt’s trial that Gray never made an identification.

Since the murder, Daulton had spent hours with Murphy, showing him a steady stream of mugshots. Murphy called the police on August 28 and said he had seen a man whom he believed was the same man he saw the morning Sykes died.

Hunt and Mitchell visited the police department the next day. Daulton had asked them to come by because the police had received information from street sources and through its Crime Stoppers program that the two men were talking about the crime. Daulton asked Hunt about his whereabouts on August 28, and Hunt said he had been at a motel on the city’s north side with his girlfriend, Margaret Crawford.

Daulton interviewed Crawford, who was 14 years old and working as a sex worker. She said Hunt and Mitchell were with her on the morning of August 10 and any other date that Daulton wanted to know about.

On September 6, Daulton assembled a photo array that included Hunt. Mitchell was not included because none of the witnesses had mentioned a person with a beard. In the array, Hunt’s background was brown. The other men had gray backgrounds. Murphy viewed the array and said he wanted to see a live lineup that included Hunt.

On September 10, Gray returned to the police station to look through a photo array. He selected Hunt from the photos.

Police arrested Crawford the next day on outstanding charges for larceny and failure-to-appear. She then signed two statements prepared by Daulton. The first said that Hunt and Mitchell had been with her at the motel on the night of August 9 but left at around 6 a.m. Hunt returned to the room about 9:30 a.m. with grass stains on his pants. In the second statement, Crawford said: “About two weeks ago me and Darryl were at the Motel 6 and Darryl was saying some stuff about the white lady that got killed downtown and Darryl said, ‘Sammy did it.’ When we were watching the Crime Stoppers on the news on the television and I said to Darryl, ‘I wish I knew who killed that lady because I could use the money,’ and Darryl said that ‘Sammy did it and he [had sex with her] too.”

Police arrested Hunt on September 11 on a charge of taking indecent liberties with Crawford. The police gave him a polygraph test about the murder, which the administrator said was inconclusive.

On September 12, Murphy viewed a live lineup and identified Hunt. Gray came in the next day. Daulton told Gray to write down the number of the person he identified from the lineup. Gray viewed Hunt, who was in position four, and the fillers, and wrote down 1-4. He would later explain that he meant that number 4 was the number one suspect. Hooper viewed the lineup but did not make an identification.

Police charged Hunt with first-degree murder on September 14, 1984. Prosecutors sought the death penalty.

A few days after Hunt’s arrest, police interviewed an employee at the Hyatt Hotel in downtown Winston-Salem. Roger Weaver said that on the morning of the murder, a man came into the hotel lobby very early and went into the restroom. A short while later, Weaver went into the restroom and saw pink water droplets in the sink and bloody towels in the trash. He said that after he saw Hunt’s photo in the newspaper, he realized it was the same man.

The indecent liberties charge was dismissed, and Hunt pled guilty on November 6, 1984 to contributing to the delinquency of a minor. The plea referenced the date of the crime as “on or about August 10, 1994,” and this specificity would become pivotal in the events that followed.

Hunt’s murder trial in Forsyth County Superior Court began in May 1985. He was represented by Gordon Jenkins and Mark Rabil. Judge Preston Cornelius presided over the trial.

There was no physical or forensic evidence connecting Hunt to the crime. Brenda Dew, a medical technologist with the North Carolina State Bureau of Investigation (SBI), testified about tests performed on blood and fluid samples taken from Sykes’s body. Hunt was type B, and Sykes was type O. Only Sykes’s blood type was found in her bodily fluids, including a vaginal sample, Dew said. “That in no way includes or excludes the blood type of Darryl Hunt,” Dew said, adding that the sperm sample found in Sykes’s body had no relationship to blood typing.

Dr. Lew Stringer, a medical examiner in Forsyth County, testified that he examined the crime scene and it was his opinion that more than one person participated in the attack. He said Sykes’s body was found about 10 yards from her shoes in an area strewn with broken glass, but her feet had no cuts. Stringer said that indicated Sykes was either carried or dragged, possibly during a struggle.

Murphy testified about what he saw on the morning of August 10 and identified Hunt as the man he saw with his right arm around Sykes’s neck.

Gray testified that he saw Hunt straddle Sykes and hit her in the face and chest. He said that he then saw Hunt flee from the scene and tuck his shirt in as he ran. Hunt’s attorneys asked Gray about his identification of another suspect, but Gray denied that he made a selection. Gray said he gave a fake name to the 911 dispatcher because he didn’t want to be involved. He said he made the name up.

Prior to trial, the state had concerns about Gray’s credibility and asked him to submit to a polygraph. While the examiner said he answered truthfully on most questions, Gray showed deception when asked whether he knew Hunt or Mitchell before August 10. That information was not given to the defense.

Weaver testified that he saw Hunt enter the Hyatt and go to the restroom at 6:45 a.m. He said he had seen Hunt at the hotel before and that Hunt had always asked permission to use the facilities. But on August 10, he didn’t. Weaver said that nobody used the restroom between the time that Hunt left and he checked the room. Weaver said he saw a pinkish substance in the sink and bloody towels in the trash bin.

Crawford had recanted the bulk of her statements to police but still appeared as a witness for the state. She first denied and then said she couldn’t remember whether she had given the police a statement. Prosecutors then moved to introduce her statement as impeachment evidence. The defense objected, but Judge Cornelius allowed the unsworn statements to be read to the jury.

Later Daulton testified about his interview with Crawford, and her statements were admitted as substantive evidence.

Mitchell testified on Hunt’s behalf and said that the two men spent the night at a friend’s house, without Crawford. The friend also testified that the two men were there. Hooper testified that Hunt wasn’t one of the men he saw near Crystal Towers on August 10.

Hunt testified and denied any role in the murder. He said that he and Mitchell got drunk on August 9, got up early on August 10, and caught the bus downtown because Mitchell had a court date. He said that police and prosecutors offered to pay him $12,000 in reward money if he would implicate Mitchell in the crime.

During cross-examination, the prosecutor asked Hunt a series of questions related to his plea of contributing to the delinquency of a minor, which referenced August 10 as the date of that crime and appeared to undercut Hunt’s testimony of where he was on that morning.

The prosecutor asked him about the plea.

“Did you look and see what the date was that they say you did it on?”

“Yes.”

“August 10?”

“Right.”

“And then you came into court and pled guilty to it?”

“Right.”

“And now you’re saying that didn’t happen on August 10?”

“I had sex with her but not on August 10.”

On June 14, 1985, after three days of deliberation, the jury convicted Hunt of first-degree murder and later recommended a sentence of life in prison rather than death.

Hunt appealed his conviction, arguing that Judge Cornelius erred in allowing Crawford’s unsworn statement to be used at trial. The appeal also said that Hunt’s right to counsel was violated because his attorneys were not allowed to be present when Weaver viewed a lineup after Hunt’s arrest.

On May 4, 1989, the North Carolina Supreme Court, in a 5-2 ruling, granted Hunt a new trial. Writing for the majority, Justice Harry Martin said that Crawford was an inherently unreliable witness and allowing the jury to learn the contents of her statement prejudiced Hunt’s right to a fair trial. The court said that Hunt’s attorneys should have been allowed to be present during Weaver’s lineup viewing, but that the issue was waived because it wasn’t properly objected to at trial.

Hunt remained in prison. He and Mitchell had been convicted in October 1987 of a separate murder in 1983 of a man named Arthur Wilson that took place outside a drink house. The North Carolina Court of Appeals granted Hunt a new trial in that case in 1988, and the state’s appeal was rejected on October 5, 1989. Hunt was released from prison. He would be acquitted at retrial and exonerated in the Wilson case on March 30, 1990.

Hunt’s second trial for the murder of Deborah Sykes began six month later, in September 1990. Hunt’s legal team had changed. Rabil was still present, but he was now joined by Adam Stein and James Ferguson, prominent attorneys who had founded the first integrated law firm in North Carolina.

The attorneys asked for a change of venue. A judge granted the request, but the new location was in Catawba County, which was more conservative and less diverse than Forsyth County. At Hunt’s first trial, the jury had one Black member. This time, Hunt’s jury was all-white with one Hispanic member.

In addition, Warren Sparrow had beaten Tisdale in the Democratic primary and later won the general election to become the new Forsyth County District Attorney. Tisdale’s defeat was in large part due to backlash in the Black community over the Hunt case. Two of Sparrow’s assistants had connections to Hunt’s defense team, and, to avoid a conflict, the case was assigned to Dean Bowman, the district attorney for two largely rural counties north of Winston-Salem.

The state’s case had also changed since the first trial. Mitchell had been indicted for murder in Sykes’s death on January 16, 1990, and he did not testify at Hunt’s second trial. Over the objections of Hunt’s attorneys, prosecutors were allowed to read Mitchell’s testimony from the first trial to jurors.

After Hunt’s first conviction, the SBI had produced a 3,000-page report on the case, interviewing old witnesses and finding new leads. Hunt’s attorneys asked for a copy of the report, but the request was denied.

Separately, the city of Winston-Salem had produced its own report on the police department’s work, which found numerous problems with the investigation and evidence that impeached the testimony of several witnesses. Daulton was demoted. Three other officers were reprimanded. Hunt’s attorneys sought to introduce the report at trial, but Judge Forest Ferrell denied the request.

Gray again testified about what he said he saw on the morning of August 10. During an interview with the SBI in 1986, Gray had said he put down the numbers 1 and 4 because the person in position 1 looked like a man he saw at the bottom of the hill. But at trial, he again testified that he wrote 1-4 because Hunt, in position 4, was the number one suspect.

Crawford’s testimony tracked her statements to police. Now, she said, Hunt had been with her on the night of August 9 but was not with her in the motel room when she woke up. She testified that he had grass stains on his pants when he returned. Crawford said that Hunt told her that he and Mitchell had just wanted to rob Sykes, not kill her.

In his initial statement to police, Murphy had said he saw Sykes with two Black men, one nearby and the other about 100 feet away. Now, he testified that there were perhaps three, maybe four, men nearby at the time he saw Sykes on August 10. He also testified that Gray was the man about 100 feet away. He said he had realized that after seeing Gray at the first trial.

Hunt’s defense team had also learned that Murphy had been a member of the Ku Klux Klan. Murphy testified that he left the Klan because of conflicting religious belief, although he still remained friends with some of its members.

The state had several new witnesses. Two inmates at separate prisons testified that Hunt had confessed to them. One said that Hunt had laughed about the crime. The other said that Hunt had told him his mistake was going into the hotel restroom to wash his hands.

Edward Reece had not been a witness at the first trial. He testified that he had been driving near Crystal Towers on the morning of August 10, and saw Mitchell, whom he knew well, coming out of a driveway, walking very fast. Reece said he called out to Mitchell, who was alone, but Mitchell didn’t respond.

Kevey Coleman had not been interviewed until he talked with the SBI in 1986. He testified at the second trial that he was walking home from a night-shift job, cutting through the field near Crystal Towers, when he saw two men and a woman approaching him. One man, who was heavier with a beard, had his arm around the woman’s waist. The other had braids in his hair. Coleman said something seemed off, because the woman had neat clothes and the men wore dirty clothes. Coleman said he heard a scream just about the time he got to his porch.

Although Coleman testified that Hunt looked like one of the men he saw, he said he did not have his contact lenses in at the time. A defense witness would testify about Coleman’s poor, non-corrected vision. In addition, Coleman’s statement to the SBI made no mention of braids.

Hunt did not testify at his second trial, but Judge Ferrell allowed parts of his testimony from the first trial to be read to jurors.

By the time of Hunt’s second trial, DNA evidence was starting to make its way into courtrooms. Hunt’s defense team asked for testing on several pieces of evidence but was told by the state that the samples were too small for testing.

During closing arguments, James Yeatts III, an assistant district attorney, told jurors that Gray probably participated in the rape and murder with Hunt and Mitchell. He said Gray’s involvement was “a question for another jury at another time.”

Bowman gave the state’s rebuttal. He asked the jurors to imagine Sykes in her final moments of life.

“What was Deborah Sykes thinking when this man right over here, this real person Deborah Sykes, what was she thinking when he spread those legs apart and he crawled down inside her and he raped and ravaged her and deposited some thick yellow sickening fluid in her body?”

On October 11, 1990, after less than two hours of deliberation, the jury convicted Hunt, again finding him guilty of first-degree murder. Ferrell re-sentenced him to life in prison. Prior to sentencing, Hunt said, “I’d like to state in open court that I am innocent even though I have been found guilty.”

Hunt appealed, claiming that Judge Ferrell had made several errors at trial, including allowing jurors to hear testimony given by Hunt and Mitchell from the first trial and excluding the SBI and Winston-Salem reports. The appeal also said that Judge Ferrell erred in not allowing the defense to cross-examine Gray about an instance in an unrelated case where he appeared to have offered to pay a witness. Separately, the defense had found a witness who said Gray admitted that Hunt did not commit the crime.

The North Carolina Supreme Court ordered a hearing on this new evidence. During that hearing, Judge Melzer Morgan Jr. of Forsyth Superior Court ordered the release of more police records and part of the SBI report. The documents included a letter from the company that the state had asked to conduct a DNA sample prior to the second trial. The letter said that although the sample was too small for its testing, more sophisticated testing was available from other providers. That possibility had not been disclosed to the defense. Judge Morgan ordered DNA testing.

In August 1994, before the completion of the DNA testing, Judge Morgan denied Hunt’s motion for a new trial. In November 1994, Roche Biomedical Laboratories reported its findings on the DNA testing. Hunt was excluded as a contributor to the Sykes sample.

Hunt’s attorneys quickly filed a new motion based on this evidence. The state pushed back, suggesting that Mitchell was the source of the DNA. Later testing excluded Mitchell, Gray, and Sykes’s husband as the source of the sample.

On November 10, 1994, Judge Morgan denied the motion for a new trial. He said that the DNA results did not meet a critical standard used by North Carolina courts in evaluating this evidence, because the results were unlikely to have changed the jury’s verdict. Judge Morgan offered his own theory of the crime, writing that either Hunt had raped Sykes without ejaculating or that he had helped another unknown person rape and murder Sykes.

Hunt appealed Judge Morgan’s ruling. On December 30, 1994, the North Carolina Supreme Court, in a 4-3 decision, affirmed the conviction. The majority opinion, written by Justice Louis Meyer, did not mention the DNA results, but said that Judge Ferrell had ruled properly during the trial.

The dissent, written by Justice Henry Frye, referenced Bowman’s closing argument where he asked jurors to imagine Hunt raping Sykes. “Given the State’s theory that the murder occurred during the perpetration of four felonies, including rape, and the fact that defendant’s defense was alibi, the report eliminating defendant as the source of the sperm taken from the victim is powerful evidence tending to weaken the State’s entire case and strengthen defendant’s defense."

On April 25, 1996, Hunt filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus in U.S. District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina. In the petition, he again asserted that his right to a fair trial was violated by the state’s failure to turn over exculpatory evidence. He also made a claim of actual innocence based on the DNA results.

On February 25, 2000, U.S. District Court Judge Frank Bullock Jr. denied Hunt’s petition. He said that Hunt’s claims on the disclosure issues didn’t amount to much and that his defense team had access to “equivalent or similar evidence.”

Judge Bullock also wrote that the DNA evidence was “simply not sufficiently exculpatory to warrant a new trial.” He said the results did not discount other possible scenarios implicating Hunt in the sexual assault. “Moreover, the DNA results do not exonerate Hunt from committing the murder, from committing the other underlying crimes of kidnaping or robbery, or from aiding and abetting any of these crimes, including the sexual assault.”

The Fourth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld that ruling, and the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear the case.

In April 2003, after Hunt’s appeals had run out, Rabil filed a motion asking the state to compare the DNA sample against DNA profiles in North Carolina’s database of 40,000 convicted felons. Judge Anderson Cromer granted the motion.

In the fall of 2003, the Winston-Salem Journal published an eight-part series on the Hunt case, which had continued to divide the city. Written by Phoebe Zerwick, the series investigated the holes in the state’s case and the shifting theory of the crime to account for the DNA evidence.

The series also uncovered new details of a sexual assault that took place in February 1985, seven months after the Sykes murder, where a young woman was kidnapped a few blocks from where Sykes was murdered. The woman picked out a suspect, but she later declined to press charges. In addition, the police at the time found no connection with the Sykes case. According to their records, the suspect in the 1985 attack was in prison in August 1984.

“Unless we are able to find the source of this DNA, which is the DNA of the real culprit, we are not going to be able to get Darryl out,” Rabil told the newspaper.

When the series ran, the state still hadn’t done the DNA analysis ordered by Judge Cromer, and he threatened to hold the officials at the state’s crime lab in contempt. In early December 2003, an incomplete sample was run against the database and turned up a partial match.

The Winston-Salem police and the SBI began reviewing the case. That led them to Willard Brown, who was the suspect in the 1985 case. He was the brother of the man with the partial match. In addition, the jail records were incorrect. Brown had been released from custody in June 1984. His DNA was not on file, but police obtained a sample from a cigarette butt retrieved during an interview at the Forsyth County Jail.

Brown’s DNA was reported as consistent with the Sykes sample. Confronted with the evidence, Brown confessed to killing Sykes, and to acting alone. He pled guilty to her murder on December 16, 2004.

On December 24, 2003, Hunt was released from custody.

On February 6, 2004, the state dismissed the charge. Evelyn Jefferson, Deborah Sykes’s mother, spoke in opposition, “What you’re about to do today is set free a guilty man, who’s guilty of my daughter’s death.”

Hunt then spoke. He said: “Mrs. Jefferson, I had nothing to do with your daughter’s death. I wasn’t involved. I know it’s hard. But I’ve lived with this every day trying to prove my innocence. I can’t explain why people say what they say. Or why they lie. Or why all this happened. Only God can. That’s how I tried to live my days in prison, knowing that only God can bring about justice. I just ask that you and your family know that in my heart you are in my prayers.”

Gov. Mike Easley issued a pardon of innocence to Hunt on April 15, 2004. Hunt later received $750,000 in state compensation and settled a federal civil rights lawsuit against the city of Winston-Salem for $1.65 million.

Hunt established the Darryl Hunt Project for Freedom and Justice, and he traveled extensively to speak out on behalf of wrongfully convicted persons. His case helped lead to the creation of the North Carolina Innocence Inquiry Commission, a state agency that investigates wrongful convictions.

Friends also said that the trauma of his wrongful conviction and the glare of the spotlight after his exoneration took a toll. He battled depression and died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound on March 13, 2016.

– Ken Otterbourg

|