Tainted Identifications

By Kaitlin Jackson and Samuel Gross

Posted on September 22, 2016

Source: The New Yorker

Eyewitness Misidentification Generally

Many false eyewitness identifications are mistakes, often the result of suggestive identification procedures by police. These unintentional misidentifications contributed to 30% of the exonerations in the Registry (572/1,886). They are the cases that come to mind when we think of eyewitness misidentification, in part because they have been studied extensively by psychologists who have recommended reforms to reduce such errors.

Other misidentifications, however, are lies. In 26% of exonerations (482/1,864), witnesses deliberately misidentified the exonerees as the guilty parties in crimes that were committed by other people. And in another 17% of exonerations (315/1,854), supposed eyewitnesses—usually the alleged victims of violent crimes—accused the exonerees of committing crimes that never happened at all.

We see a few common patterns across all these false identifications, lies and mistakes alike:

-

Misidentifications by witnesses who know the suspect are generally lies.

-

Misidentifications by strangers are generally mistakes.

-

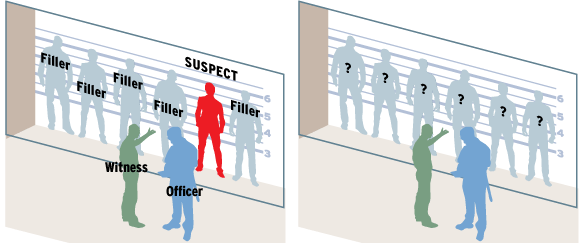

Police initiated identification procedures, generally in-person or photographic lineups,

almost always involve witnesses who are strangers to the suspect.

- On the other hand,

when a witness accuses someone she knows, accurately or not, no identification procedure is held; she simply tells the police who did it. No one needs a lineup to identify (or misidentify) her brother.

Suggestiveness and Deliberate Misconduct

Police often conduct unnecessarily suggestive identification procedures. That's true of most showups, in which the suspect is presented to the witness alone. And it's true of many lineups—for example, when the suspect is clearly several years younger than the non-suspects who are placed in the lineup for comparison, or several inches shorter. Suggestive procedures like these are bad practice, but unless they are deliberately done to influence the identifications, they are not misconduct.

In some cases, however, the police go beyond suggestiveness and use identification procedures to deliberately induce witnesses to identify suspects whether they recognize them or not. That is misconduct. It corrupts the investigation and produces tainted identifications.

How does this happen? There are three different paths:

- In most cases, the

police manipulate an eyewitness into mistakenly believing she saw a suspect she didn't actually see.

- Other times, the

police convince the witness that they—the police—know the suspect is guilty, which may lead the witness to lie and identify a suspect she doesn't recognize in order to help the police get a conviction.

- Some witnesses are

induced to lie and identify innocent suspects out of self-interest: they are promised benefits if they do, or threatened with harsh consequences if they don't, or both.

Source: Brian Moore/Orange County Register

How common are Tainted Identifications?

The Registry recently reexamined the first 1,365 exonerations we listed, those posted through April 2014. We found some type of false identification in 75% of the cases (1,018/1,365). Ninety of these exonerations included identification procedures that produced tainted identifications—7% of all exonerations and 9% of those with any type of misidentification.

This suggests that tainted identifications are a serious but comparatively uncommon problem among exonerations. But there may be more. Deliberate misconduct is usually hidden from sight. We certainly missed some exonerations in which the police successfully concealed the stratagems that produced tainted identification, but we don't know which or how many.

In 57% of the tainted identifications we did find, the witnesses made mistakes (51/90), and in 43% they lied. The actual proportion of lies is probably higher, since we only coded an identification as a lie if we saw clear evidence of deception, and lying—like all misconduct—is often successfully hidden.

Patterns OF Tainted Identification

Most of the misconduct that produced these tainted identifications fell into four common patterns. (There were also several less common patterns, and some tainted identifications fell into more than one category.)

Telling. Nearly half of tainted identifications occurred after police told the witness who to pick (43/90). Sometimes they did so in the context of a deal. In Randall Adams' case, for example, the eyewitness described the perpetrator as "African American or Mexican," and was initially unable to pick Adams (who was white) from a lineup. She identified Adams after an officer offered to drop robbery charges against the eyewitness's daughter in exchange for the identification.

In 12% of exonerations with tainted identifications (11/90), police not only told witnesses who to identify but threatened those who were reluctant to do so. In Jose Garcia's case, police told an uncooperative 14-year-old eyewitness's mother that they would "go after the boy" if she didn't identify Garcia herself. She picked Garcia in a live lineup after police showed her his picture.

The great majority of identifications produced by

Telling were

lies; in a few, the witnesses may have come to believe that they actually saw the suspects they were told to identify.

Displaying. In 32% of tainted identification cases, police visually highlighted the suspects in lineups (29/90). Some exonerees were put in lineups in which they were the only members of their racial group; others were dressed in prison clothes while the others in the lineup were not; and some were made to wear the clothes the perpetrator was described as wearing. Thomas Doswell was picked in a photo lineup in which he alone was holding a billboard with the letter "R" (for rapist) on it.

Most false identifications resulting from

Displaying were

mistakes.

Repeating. In 14% of tainted identifications, the exoneree was displayed to the witness time and again, usually in lineups in which he was the only person who was included in multiple presentations (13/90). If that happened three or more times before the exoneree was identified, we coded the identification as tainted. For example, the eyewitness who misidentified Keith Harris at his trial for robbery and attempted murder trial saw Harris or pictures of him three times during the investigation—including in the last two of seven different lineups the witness viewed—before he finally picked him.

All misidentifications based on

Repeating were

mistakes.

Lying. In 7% of cases with tainted IDs (6/90), police used false information to explain away discrepancies between the suspect and the eyewitness's initial description. In Albert Johnson's case, for example, after the eyewitness said that Johnson was too light-skinned to be the perpetrator, a detective told the eyewitness—falsely—that Johnson's skin had lightened because he spent years in prison with little exposure to the sun. In Todd Neely's case, the false information was provided visually: The eyewitness described the perpetrator as a 16-year-old, but Neely was older and looked his age—so police placed a high school photo of Neely at 15 in a photo lineup.

As with Repeating, all misidentifications based on

Lying by police were

mistakes.

Kaitlin Jackson, an Assistant Public Defender at Bronx Defenders in New York, worked for two years as a Research Fellow at the National Registry of Exonerations.

Samuel Gross is co-founder and Senior Editor of the Registry.