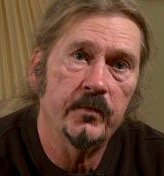

Victor Burnette

The Crime

In the early morning hours on August 3, 1979, an 18-year-old woman went to sleep in her first-floor apartment, where she lived alone, after a night out with her friends. Due to very hot weather, she left the main door and the drapes open, and locked only the screen door. She woke up at 3 a.m. to find a man on top of her; he told her to stay still and sexually assaulted her. The victim testified that as the attacker was leaving, she “got a very good look at him” in the moonlight shining in from the window.

The Investigation and Identification

After she was attacked, the victim called the police. She described her rapist as a white man, about 5-feet 8-inches tall, weighing about 160 pounds with long blond hair and a mustache. The victim’s sheet was collected as evidence and she was taken to the hospital, where a rape kit was collected.

The following night, the victim was sleeping at her boyfriend’s house when she heard noises from the street at 2 a.m.; she looked out the window and felt certain that she saw her attacker. Hiding her face, she called out to him to hear his voice — and she was sure from his response that it was her rapist’s voice she heard. He left the area and she did not inform the police of this sighting.

The next day, she met with a detective in an unmarked car in front of her apartment to put together a composite drawing. While with the detective, she noticed Burnette walking down the street. Upon being spotted, he promptly walked in the opposite direction, arousing suspicion. Another officer apprehended him a short time later with an open can of beer in a nearby alley.

The victim identified Burnette as her attacker, although he had a beard and wore glasses and she had not mentioned these features in her description of the attacker.

The Trial

State forensic analyst Mary Jane Burton testified at Burnette’s trial that she examined pubic hairs from the rape kit and the victim’s sheet. She said one hair "was consistent" with Burnette, others with the victim, and yet another was consistent with neither Burnette nor the victim. She did not present qualifying information about the limitations of hair microscopy. She also determined that sperm cells were present on the vaginal swab from the rape kit. Serology testing, however, only showed the presence of Type A blood antigens. She testified that the victim was Type A and Burnette was a non-secretor, meaning his blood type cannot be determined from bodily fluids like semen and saliva. The serology testimony was misleading because it did not discuss the possibility that the victim’s blood group markers masked the perpetrator’s, meaning that in actuality no man could be excluded from the sample.

Burnette testified that he was at a bar from 11 p.m. to about 2 a.m. on the night of the attack. After leaving the bar, he said he returned to his home, which was two blocks from the victim’s apartment. He was a night caregiver for his blind and arthritic grandmother, who confirmed that Burnette arrived home just after 2 a.m. They spoke briefly and she heard him go to sleep. She said her hearing was good and she always knew when someone was entering or leaving the house. During the police investigation, Burnette had incorrectly told a detective that he was home the entire evening. At trial he admitted he had confused that night with another night, and that his drinking problem caused this memory lapse. Burnette also testified that he had walked away from the detective and victim when they were in the car because he had an open can of beer and did not want to be stopped by police.

On October 23, 1979, a Richmond City jury convicted Burnette of rape and burglary. He was sentenced to 25 years in prison.

Post-Conviction and Exoneration

Burnette’s appeals were denied. After seven years in prison, he was released on parole in 1987. Although free, he continued his quest to clear his name. He repeatedly visited a state forensic facility in Richmond to ask if evidence from his case had been retained. He remembers being told: “if you’re found guilty, your stuff is destroyed.”

Due to his rape conviction, Burnette was unable to secure employment while on parole; he taught himself carpentry and began a one-man home improvement company, constantly struggling to make ends meet. He was discharged from parole in 1993.

In December 2005, Burnette read an article in The Richmond Times-Dispatch newspaper, detailing how Julius Ruffin and Arthur Whitfield had been cleared of their convictions through DNA evidence. Both cases involved evidence that was purportedly lost until it was later discovered in the files of serologist Mary Jane Burton, who by then was deceased. Burnette immediately recognized her name as the serologist who had testified at his trial. He contacted the lab and requested another search for evidence from his case. It was found in Burton’s files and forwarded to Richmond prosecutors.

In 2006, DNA tests were conducted on the evidence from the rape and on samples from both the victim and Burnette. The comparison proved that Burnette was not the source of the semen from the crime scene.

Burnette’s petition for a writ of innocence was denied on April 17, 2007 because he was not incarcerated at the time of the petition, a requirement of the law at that time. Burnette filed a petition for absolute pardon in 2007, and it was granted two years later on April 6, 2009 by Virginia Governor Tim Kaine. In 2009, the state also amended the law governing writs of Actual innocence, removing the requirement that petitioners be incarcerated to qualify.

It took three full decades after Burnette’s conviction for him to be fully cleared. He was the first person exonerated under the Virginia Old Case Testing Program in which state officials were reevaluating convictions where DNA could potentially prove innocence, and the sixth person to be exonerated from Burton’s files of forensic evidence. Although Burton’s method of storing evidence in her notebook contradicted lab policies, the stored evidence played a key role in overturning wrongful convictions.

In 2010, Burnette, who had continued to run his one-man home improvement company in Richmond, was awarded $226,000 in state compensation.

By the end of 2013, Burnette, Ruffin, Whitfield and eight other men– Marvin Anderson, Curtis Moore, Willie Davidson, Philip Thurman, Thomas Haynesworth, Calvin Wayne Cunningham, Bennett Barbour, and Garry Diamond–also had been exonerated as a result of the testing of evidence in Burton's files. In 2018, Roy Watford III became the 12th person to be exonerated by DNA testing of evidence in Burton’s files. In 2019, Winston Scott became the 13th person exonerated by DNA evidence retained in Burton’s files. |