Andrew Wilson

At that moment, another man came to the open driver’s side window and said, “Give your money, man, or you’re gonna die.” The man then took Hanson’s wallet and stabbed him 10 times. Both men then walked away.

Hanson, who had a disorder that prevented his blood from clotting, died at the scene. Police recovered several pieces of a broken knife, a hat and some palm prints.

The following day, Bishop looked through more than 1,500 police mug shot photos and selected a photograph of Johnny McKinney as the man at the passenger side of the truck. However, that was wrong—McKinney was in jail at the time of the crime. Among the photographs she viewed, but did not select, was that of 29-year-old Andrew Wilson.

On October 25, 1984, Bishop returned to the police station and went through the same photo books again. This time, she identified the photograph of Marshaunt Jackson as a man who had an altercation with Hanson four days before the murder. Again, she passed over the photograph of Andrew Wilson.

Three days later, Bishop helped create composite sketches of two men. On November 2, 1984, Detective Richard Marks took Bishop for a drive through the neighborhood looking for the suspects. She pointed to Walter Gibson, who was sitting at a bus stop, and said he was the man at the passenger side of the truck. However, she later recanted that identification after hearing Gibson’s voice.

Marks took Bishop for two more ride-alongs on November 14 and November 15 that were not successful.

On November 20, nearly a month after the murder, Byron Berwick, who operated a drug abuse outreach center on Hobart Boulevard, told police that on the day of the murder Marshaunt Jackson came to the center “quite drunk” and was turned away. Berwick said that about “10 or so minutes later,” he heard screaming from outside. Berwick said he came outside and found Bishop screaming and then saw two men about 35 or 40 feet in front of Hanson’s truck walking away. Berwick could not say if Jackson was one of the two men. He also said he had not seen Jackson since that night. Jackson was questioned and denied involvement and was eliminated as a suspect.

At about that time, Christopher Hanson’s father, Arthur, who had been conducting his own investigation and had offered a reward for information, told Detective Marks about a possible witness named Clarence Pace. During an interview with Marks, Pace said he and two other men were walking in the neighborhood when they saw two black men come around the corner of Hobart onto 22nd Street and jog toward them. When they reached Pace and his companions, one ran on the right side and the other ran on the left side. Pace said the pair jogged to 23rd Street and then broke into a dead run.

Pace said that one of the men resembled a man he knew as “A.D.” who hung out with a man named Frederick Terrell. Pace looked at police mug shot books and said he was 80 percent sure Andrew Wilson was “A.D.” Pace said Wilson was wearing a leather jacket. Pace’s companions were unable to identify anyone.

Marks was familiar with Andrew Wilson because Marks often ran into Wilson on the street along with Terrell. Wilson had been arrested several times in the past on suspicion of committing burglaries, but had been released.

Marks would later testify that he suspected Terrell as the second man, although Pace said he had known Terrell for more than 10 years and insisted that Terrell was not the second man.

Nine days later, on November 29, 1984, Detective Marks assembled a photographic lineup for Bishop that contained 16 photographs, including photographs of Pace, Jackson, Terrell and Wilson. Bishop tentatively identified Terrell as the man who leaned into the passenger window, but was unable to identify the man who stabbed Hanson. Bishop, according to Marks, then identified Wilson as the stabber, saying she was 70 to 80 percent sure. However, her initial description of the stabber was of a man wearing a plaid button-down shirt, while Pace said the man was wearing a leather jacket.

On December 2, 1984, Terrell was arrested. Two hours later, Terrell’s cousin, Vincent Sanders, contacted Marks to say that Terrell was not involved in the murder, but that he had heard Andrew Wilson and a man named Ricky Wilson talking about having committed the crime. Detective Marks showed a photographic lineup containing Ricky Wilson’s picture to Pace and Bishop, but they did not identify him.

Detective Marks prepared an arrest warrant for Wilson and stated in his sworn affidavit that he had directed Bishop to Wilson’s photograph in the photo lineup. Despite this admission, the warrant was issued. On December 3, Wilson learned he was being sought for questioning and came to Marks, saying, “You know I don’t do stuff like that.” Marks then arranged for live lineup for Andrew Wilson and Bishop identified him as the man who stabbed Hanson. She also viewed a lineup containing Terrell and when asked if she saw the man on the passenger side, she said it was either Terrell or another person in the lineup.

After the lineup, Marks drove Bishop home. Marks later testified that along the way, she “muttered something out loud like a light had just come on, to the effect that that she had known (Wilson), she knew of him.” The statement, however, was not recorded in the case file.

Based on the identifications, Wilson and Terrell were charged with first-degree murder and robbery with a weapon.

In May 1986, while the case was awaiting trial, Pace was arrested for “joy riding.” While in the Los Angeles County Jail, he saw Wilson and told Wilson that he had lied to police about Wilson’s involvement in the crime.

In June 1986, Terrell’s lawyer filed a motion challenging the case against Terrell after Pace provided a sworn affidavit saying he was certain that Terrell was not one of the two men he saw that night. The prosecutor, Deputy District Attorney Laura Aalto, questioned the detective and he admitted to her that he had orchestrated his interview of Pace in such a manner that Pace would not eliminate Terrell. Although Aalto then decided to dismiss the charges against Terrell because the case against him was “shaky,” the report of Marks’s admission about his interview with Terrell was not disclosed to Wilson’s defense lawyer.

On October 21, 1986, Wilson went to trial in Los Angeles County Superior Court. The prosecution’s theory was that Wilson and Terrell committed the crime together, even though the prosecution had dismissed the charges against Terrell. No physical or forensic evidence linked Wilson to the crime and Marks’s affidavit for the arrest warrant in which he admitted directing Bishop’s attention to Wilson’s photograph was not included in the reports and documents disclosed to Wilson’s defense lawyer. Marks, however, did admit under cross-examination that “at some point” he had pointed to Wilson’s photograph.

Pace testified that he was 80 percent certain that he saw Wilson and another man run past him within two blocks of the murder. Sanders, who had recanted his testimony prior to trial, was called as a witness as well. He said, “I don’t know nothing about the crime.” He claimed that his prior statement was false and that Detective Marks coerced it by threatening “to put me in jail.” As a result, a tape recording of Sanders’s statement that he overheard Wilson bragging that he had committed the crime with Ricky Wilson was played for the jury.

Bishop testified and identified Wilson as the man who robbed and stabbed Hanson. She also told the jury that she identified Wilson from police mug shot books nearly six weeks after the crime, that she helped create a composite drawing of both suspects and that she had identified Wilson in a live lineup.

Bishop also testified that Wilson telephoned her from the jail, posing as a prosecutor saying that Andrew Wilson was innocent. She said Wilson made two more calls, identifying himself and saying, “Please don’t press charges, because I didn’t do it.” Bishop said that she knew of Wilson prior to the crime, but only because a member of her family had met Wilson one time. Bishop said that she did not otherwise have contact with him or his family.

In response to that testimony, Wilson’s defense attorney called Wilson’s wife, Phyllis, as a witness to testify that Bishop was well known by the Wilson family. Phyllis testified that Bishop not only babysat for their children as a 14-year-old, but also lived with them for a short period after she ran away from home.

The jury deliberated for three days before convicting Wilson of first-degree murder and robbery on November 12, 1986. He was sentenced to life in prison without parole.

Wilson lost his direct appeals. In 2012, 26 years after he was convicted, Wilson was helping a fellow inmate, Horace Burns, with his legal work and discovered that Burns’s attorney had uncovered a payment of $1,000 that Detective Marks had arranged for Bishop to help pay her rent and other expenses. That payment had not been disclosed to Wilson’s trial defense attorney. In 2014, attorney Jon Aminoff, who represented a defendant in an unrelated case, contacted Wilson to report that Detective Marks had coerced a witness to falsely identify that defendant—that same conduct Wilson claimed Marks engaged in during Wilson’s case.

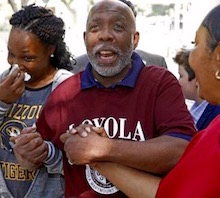

In 2015, Aminoff and Wilson contacted the Loyola Law School Project for the Innocent (LPI) in Los Angeles, California, and a re-investigation of Wilson’s case commenced.

In August 2016, LPI filed a state law petition for a writ of habeas corpus on behalf of Wilson. The petition said that Marks had coerced Pace and Bishop to falsely identify Wilson. The prosecution, the petition said, knew that Marks had coached and manipulated the witnesses, knew that Marks had admitted directing Bishop to Wilson’s photograph in the photographic lineup, and failed to disclose the $1,000 payment Marks arranged for Bishop prior to Wilson’s trial.

“This case is a classic example of law enforcement subjecting key prosecution witnesses to blatant and conscious cues designed to influence identification,” the petition said.

At the same time, the trial prosecutor, Aalto, provided a sworn statement saying she would not oppose the vacating of Wilson’s convictions because the case had always troubled her.

The petition also provided new evidence that Bishop testified falsely when she said she was not familiar with Wilson at the time of the crime. Wilson’s daughter, Catrina Berks, gave a sworn statement that Bishop “often” babysat for the family and sought refuge with the Wilson family after running away from home.

Other evidence that was not disclosed to Wilson’s defense lawyer included reports that a few months prior to Wilson’s trial, Bishop claimed that a man abducted her and attempted to rape her, but she escaped. The man was not charged, however, because the prosecutor—Aalto—concluded that Bishop was lying about the incident. Aalto conceded in an interview with Wilson’s lawyers in December 2016 that she did not disclose it because Bishop “never had any credibility anyway.”

Aalto also failed to disclose to Wilson’s defense lawyer that Earl Martin, who was murder victim Christopher Hanson’s best friend, contacted the prosecution prior to Wilson’s trial and reported that he believed Bishop had stabbed Hanson. Martin said that Bishop had stabbed Hanson in the past, possibly while high on drugs, and had assaulted Hanson on several occasions (one requiring a trip to the hospital). Martin told Aalto that at the time of Hanson’s murder, Hanson was trying to persuade Bishop to move back home with her family or into a halfway house to deal with her drug problems, but that Bishop became enraged when the topic was raised. Martin also asked to see the knife used to kill Hanson (only broken pieces were found) because one of his knives from his toolbox was missing. Aalto did not disclose Martin’s statement to Wilson’s defense attorney, and she did not ask Detective Marks to investigate the matter.

On March 15, 2017, Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge Laura Priver vacated Wilson’s convictions and ordered Wilson released. “I think this is justice,” the judge declared.

Deputy District Attorney Erika Jerez said that “cumulative errors” had infected Wilson’s case and that the prosecution would not refile the charges against Wilson. However, she had sent a letter to the judge said that while it was clear that Wilson was “denied a fundamentally fair trial, we do not believe Mr. Wilson is factually innocent.”

In July 2018, lawyers for Wilson filed a federal civil rights lawsuit seeking compensation for his wrongful conviction. In 2019, Wilson filed a claim for compensation from the California Victim Compensation Board. Wilson was awarded a certificate of innocence and received $1,650,880 in state compensation on May 20, 2021. In November 2021, Wilson settled his federal lawsuit for $14 million.

In August 2022, Wilson made a $1 million gift to California State University, Los Angeles, to become the founding donor of the school's new Los Angeles Innocence Project.

– Maurice Possley

|